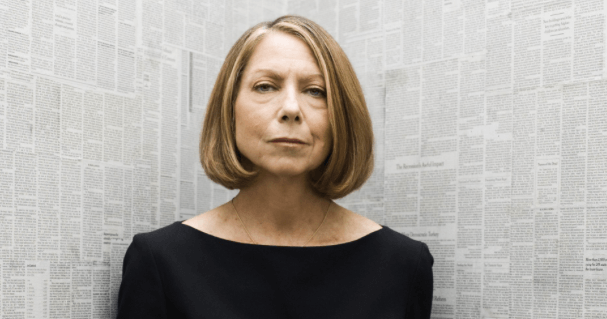

On Impostor Syndrome and Why Jill Abramson’s Firing Has Rattled Women In the Media

If she doesn’t belong, who among us does?

When news came yesterday of Jill Abramson’s abrupt dismissal from her post as Executive Editor of the New York Times, the response from many women in the media was swift and near-unified in its outrage. Even before the rumor mill had any significant grist upon which to run, consensus was that Abramson had been fired for being not only a woman, but also for being a certain kind of woman, one who is, as an anonymous source told Ken Auletta of the New Yorker “pushy.” Which, Auletta notes, is “a characterization that, for many, has an inescapably gendered aspect.” And then, of course, Auletta also leaked another possible reason for Abramson’s dismissal, namely, that she had asked for a raise because she discovered that her salary and benefits package were significantly less than those of her male predecessor, Bill Keller. (The Times, for its part, responded, “Jill’s total compensation as executive editor was not meaningfully less than Bill Keller’s, so that is just incorrect.” No further details as to what qualifies as “meaningful” were forthcoming.) Almost immediately as the news broke, then, it transformed from simply being a conversation about why Abramson was fired, and into one about how she was fired because she was a woman.

As the first woman to hold the prestigious job of Executive Editor of the Times, Abramson was seen as something of a professional hero for many women in the media—she represented that best that we could all hope to achieve. In a profession still overwhelmingly dominated by men—especially white men—the reality of a woman having risen to the top of such a storied institution seemed like a sign that progress was being made, and would continue apace. Add to that the fact that Abramson was a bit of an iconoclast (she sports four tattoos and, sure, two of them are about as staid as can be—a crimson Harvard “H” and a Times “T”—but still), outspoken on feminist issues (including her excellent account of the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill case), and turned her experience of being run over by a truck into an excellent, collaborative piece of long form journalism, and it’s pretty easy to see why Abramson stood out as a beacon to many other women in media. So the outrage that many women (and, to be fair, many men) are expressing over her firing is understandable simply on the level of the visceral anger that comes with witnessing an injustice like this, but there’s also much more to it than that, and it speaks to the insidiousness of the sexism that still pervades many professional spheres.

Professional women are constantly bombarded with advice intended to help erase the gender disparities that exist within the modern workplace. “Lean in!” “Ask for more!” “Project confidence!” And all of these commands are designed to erase the stereotypically feminine qualities which hold women back and allow men to advance in their stead. And yet despite (or even because of) the fact Abramson clearly embodied these maxims to the extent that any woman—or man—could, she was fired. How could this not make every woman who feels like she has to fight for a seat at the table feel like her position at work is far more tenuous than she’d been led to believe? How could this not make every woman who has advanced in her career wonder whether or not her male superiors are ready at the drop of a hat to replace her with a man? As Amanda Marcotte writes today, Abramson’s firing “speaks to the deep, immoveable, and totally realistic fear many women have that there’s nothing they can do to overcome sexism in the workplace.”

But even beyond the fear that the patriarchy is so entrenched that there’s nothing women can do to combat it, there’s another underlying fear that is related specifically to how brief Abramson’s time at the top was, and that’s impostor syndrome. One of the notable things about Abramson’s tenure is how short it was; she served only two-and-a-half years as Executive Editor, and had been expected to last about another five. (Most senior Times-staffers leave their positions at the age of 65, Abramson is now 60.) This abbreviated time period only contributes to the idea that the first female Executive Editor of the Times was something of a sham or a fraud, which is something that all too many women feel like already in the workplace. Add to that the fact that Abramson wasn’t even allowed to take something of a victor’s lap following her dismissal, to say a decent and deserved farewell to the staffers with whom she had long worked, and it seems even more evident that the Times is implying that Abramson never really belonged in the top position to begin with. This is one of the sickest tricks that any male-dominated industry can play on women (or, for that matter, any marginalized group), because so many women already question how it is that they got their jobs, and if they really deserve to be where they are. In fact, one of the reasons that there is so much chatter about leaning in and confidence gaps is because women don’t give themselves enough credit for deserving what they’ve earned. Part of this is due to the need that women feel like they have to be “twice as good” (something that minorities have also long struggled with), but mostly it has to do with being treated (both implicitly and explicitly) as little more than guests at the table—even when they’re seated at its head. And so this is why Abramson’s firing is so rattling for women in the media and beyond, we’ve all just been reminded that no matter how irreplaceable we’ve been told we are, there’s always a man ready to remove us, and another one prepared to take our place.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like