A New Type of Poverty: How the iPhone Became a Placebo for the Poor

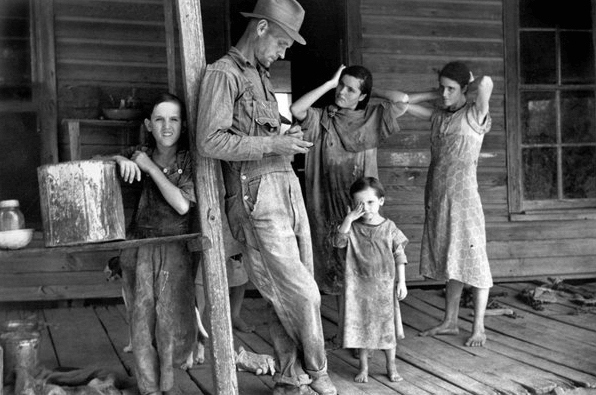

This is not what poverty looks like in America anymore.

The face of poverty in America has changed dramatically from what Walker Evans and James Agee indelibly captured in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, their book documenting the lives of our nation’s poverty-stricken tenant farmers during the Great Depression. Now, an American family living at or below the poverty line is almost guaranteed to have not only such basic necessities as indoor plumbing or refrigerators, but also things like high-speed Internet access, multiple cars, and video game systems. Young adults who can only find work as an intern or at a minimum wage job might need to live at home with their parents, but they probably have iPhones and a well-stocked wardrobe. And yet while it might in many ways seem that contemporary lower-income families and individuals are not suffering at the level of poverty-stricken Americans in the past, the gains that have been made are actually superficial, and only serve to hide the larger systemic poverty problem that faces us today.

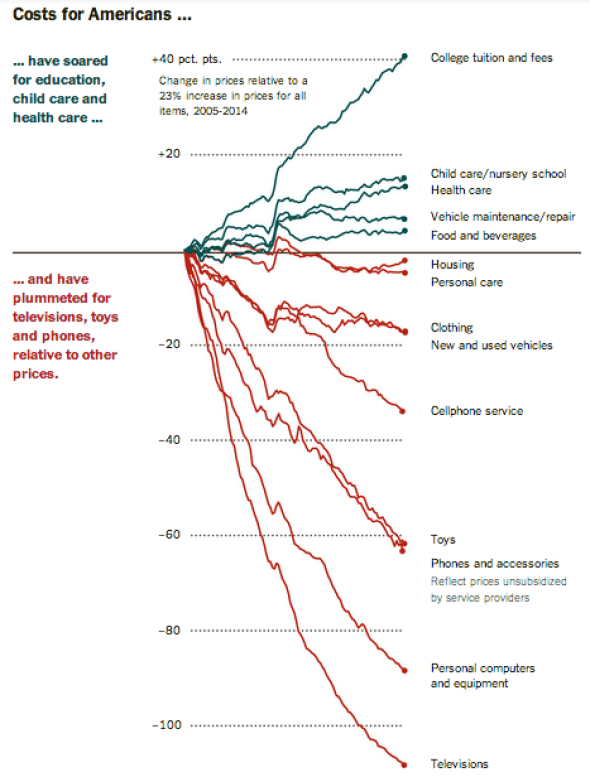

A recent article in the New York Times, “Changed Life of the Poor: Better Off, But Far Behind,” opened with the question, “Is a family with a car in the driveway, a flat-screen television and a computer with an Internet connection poor?” As the real prices of what were once thought to be luxury goods (computers, smart phones, cars, etc.) have plummeted (see chart below), “Americans—even many of the poorest—enjoy a level of material abundance unthinkable just a generation or two ago.” And in conjunction with the lower prices of factory-produced goods has come an increased reliance on possessing the kind of updated technology that is now a mandatory part of participating in the workforce. It isn’t just a case of everybody being able to buy a smart phone or afford Internet access, many people need to have these things in order to stay connected to their places of employment when they’re not at work. In effect, the luxuries have become necessities, which has luckily come along with the ability for many to be able to afford to buy them. And perhaps, this would be a good thing—a true advancement in the decades-long war on poverty—if it weren’t for the fact that the things that are necessary to end the cycle of poverty are now priced like luxury goods.

It has been a long-established fact that one of the few guaranteed ways of ascending the social and economic ladder is through higher education. Even during the recent (ongoing) recession and spike in unemployment, the employment prospects for high school graduates versus college graduates was not only clearly favorable for college grads, but data also proved that the wage gap between college and high school grads continues to widen. And yet, more and more high school students are opting out of college because they deem it “not worth it.” This is in no doubt due to the astronomical costs of a college degree coupled with the knowledge that, once matriculated, potentially tens of thousands of student loan debts will need to be paid off. And then there are other costs which should not fit into the “luxury” category, things like childcare costs or the price of food. Yet those costs have risen dramatically as well, leading to situations wherein a family might have an iPhone but can’t afford to keep milk in their refrigerator. Adding to the strain on low-wage earners is the fact that the most expensive things tend to be those that need to be paid for repeatedly, and so there’s no respite for these families. They might be able to afford a one-time purchase of an iPad, but they can’t keep up with their monthly health insurance payment.

Poverty, of course, isn’t just about the people who are suffering from its constraints. It’s something that affects society as a whole, and not least in the ways in which it’s politicized. The fact that Republican lawmakers like Representative Paul Ryan can now point to the fact that the standard of living for low-income Americans has increased because of things like indoor plumbing and almost universal access to electricity and, of course, the reduced prices of electronic goods, means that these same lawmakers want to cut benefits like Medicaid and Pell grants and food stamps for the people who still desperately need access to these things. The problem is that the possession of an iPhone doesn’t mean anything to a person who faces the kind of instability that comes with barely being able to afford rent and student loan bills and car payments. And anyone who points to the iPhone as proof that the punishment for being poor isn’t as harsh as it once was, fails to understand what the punishment of being poor has always been and continues to be. The real punishment of poverty is its intractability and the insecurity that those who bear its burden face. The real punishment of poverty is that it’s almost impossible to escape its clutches, especially now as the wage gap increases and the potential for social mobility decreases. And owning an iPhone isn’t going to change that for anyone.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

c/o nytimes.com

You might also like