The Problem with Sansa Stark: In Defense of One of the Most Hated Characters in Game of Thrones

Nobody wants to be Sansa. This is what I learned from (what else?) taking the BuzzFeed quiz “Which Game of Thrones Character Are You?” and by discussing it with, oh, anyone who would let me talk about BuzzFeed quizzes and GoT with them. Acceptable results on this quiz (for women and men alike!) include Daenerys Targaryen, Arya Stark, Tyrion Lannister, Jon Snow, Brienne of Tarth, and Jaime Lannister. Even Cersei Lannister was a fine character to get because, well, mainly because of Lena Headey. But there was one character with whom not a single person wanted to be associated, one Westerosi for whom there was nothing but contempt and dismissal, and that was Sansa Stark, about whom most people with whom I’ve spoken have this to say, “She’s the fucking worst. She should have died instead of her dire wolf.” (Oh, right. Some light spoilers ahead, I guess, though nothing past the third season of the television show. But also, you should really be caught up by now.)

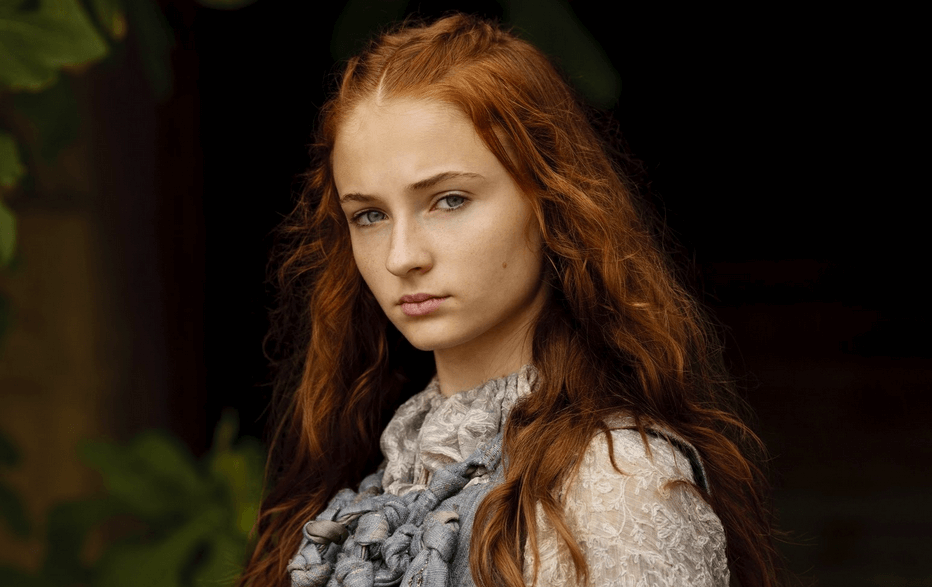

Sansa Stark, eldest daughter of Ned and Catelyn Stark, is a beauty. She loves to do needlework, has impeccable manners, and—for a time anyway—wants nothing more than to be married to Joffrey Baratheon, future king of Westeros. Sansa represents everything to which a highborn young woman of Westeros should aspire: she is lovely to look at, obedient to those in positions of authority, and, well, nothing else really matters because those are the two main qualities prioritized for young women in the Seven Kingdoms, and Sansa embodies them completely. In contrast to Sansa, her younger sister, Arya, is willful, brash, drawn to swordplay, and described as being “horsefaced.” In “The Women and the Thrones,” his essay on feminism and Game of Thrones, Daniel Mendelsohn sees the two sisters as representing “two paths—one traditional, one revolutionary—that are available to Martin’s female characters, all of whom, at one point or another, are starkly confronted by proof of their inferior status in this culture.” Mendelsohn continues, “all the female figures in Martin’s world can be plotted at various points on the spectrum between Sansa and Arya Stark. It’s significant that the older generation tend to be less successful (and more destructive) in their attempts at self-realization, while the younger women, like Arya and Daenerys, are able to embrace more fully the independence and power they grasp at.”

Sansa, of course, while not being from the older generation, is clearly of it, and suffers greatly for her adherence to the code of behavior that has been instilled in her from birth. Of course, Sansa is not alone in her pain. None of the women (or, for that matter, men) are immune to the exigencies of survival in the Game of Thrones world. But whereas characters like Arya and Daenerys face their trials (which are sometimes, literally, by fire) head-on, and then frequently triumph where almost all others—female or male—would fail, Sansa shies away from rejecting the system in which she has long thrived, the one which she thought would always provide her a safety net.

In doing this, Sansa differs from other women of prior generations who tend to recognize the limitations inherent with being a woman, yet attempt to work within those constraints to secure power in any way they can. And so whether it’s Cersei, who curses the fact that it’s her twin brother who gets all the glory (“When we were little, Jaime and I were so much alike that even our lord father could not tell us apart… We were so much alike, I could never understand why they treated us so differently… He was heir to Casterly Rock, while I was to be sold to some stranger like a horse, to be ridden whenever my new owner liked, beaten whenever he liked, and cast aside in time for a younger filly. Jaime’s lot was to be glory and power, while mine was birth and moonblood“), and so grasps for power through her most potent currency, her children; or Catelyn, who needs to invoke the name of her lord father in order to (misguidedly) arrest Tyrion Lannister for the attempted murder of her son Bran, the women after whom Sansa models herself might appear more “traditional” than Arya or Daenerys, but are still not meek and powerless in the manner of Sansa. Yes, both Cersei and Catelyn are hobbled by an entrenched patriarchal world, but because they attempt to work within those boundaries to achieve power on their own terms—while Sansa, emphatically, does not—it’s far more common to hear fans of GoT (especially those who are only familiar with the television series) to defend Cersei as being evil mainly due to the fact that her ambitions were stifled because she’s a woman, and Catelyn for doing foolish and spiteful things (most notably to Jon Snow) because she acts out of a strong, fierce love for her family.

Sansa, meanwhile, is seen as being achingly passive, or even, at times, as someone who naively (or perhaps stupidly) acquiesces to the wishes of the evil people around her (like Cersei and Joffrey) at the expense of her loved ones. Sansa is despised for having no agency, and she is condemned for prioritizing the needs of her future family over that of her birth family. But most of all, Sansa is hated for being a woman. Oh, not just any kind of woman, but a specific kind of woman. There are, of course, some women in Game of Thrones who are admired and even revered, though many of them do possess characteristics more frequently associated with men. But it is not only the gender-subversive Arya or Brienne who are beloved by fans of the series, but also Daenerys, who leads with strength, and yet is most definitely feminine who is adored as well. Sansa is thought to be a different type of woman, though, one whose passivity signifies weakness, one whose obedience means cowardice. But this is patently unfair to Sansa, whose greatest flaw is that she had a slower learning curve than we wanted her to once her world fell apart.

Sansa Stark is the ultimate example of how precarious the positions are of even the most privileged woman, and why relying on patriarchal institutions for protection holds little benefit for women and only serves to strengthen their oppressors. For Sansa’s entire life, she was taught that if she acted a certain way and looked a certain way, her life would turn out a certain way. She had no reason not to believe this, and because her nature and her talents and her physicality aligned so perfectly with what the ideal Westerosi woman was supposed to be, it was easy for her to play that role. Except that, for Sansa, it wasn’t just a role; it was who she was, and who she wanted to be. In contrast, Arya never could have been another Sansa. Arya was not cut out for afternoons of embroidery or bearing children or being admired. Arya is feisty and Arya is a rebel, and while that’s admirable and interesting and makes for a fascinating character, it is not representative of any type of norm, and so it is harder to draw any greater lessons from Arya’s narrative than that she is exceptional, and would probably thrive no matter the situation because Arya is as nimble in a turmoil-filled world, as she is when she wielding her sword, Needle.

Arya’s rebellious nature serves her well, because even before Arya learns for certain that Joffrey and Cersei are sociopaths, she doesn’t trust them based on her instinctive disdain for everything respectable. But for Sansa, Joffrey and Cersei represent everything that she has been told (by not only society, but also her family) she should aspire to be. In fact, despite the fact that Ned and Catelyn Stark know that Cersei is not to be trusted, they still willingly endorse the betrothal of Sansa to Joffrey. And because Sansa has been brought up to value loyalty and family and obedience to those in power, is it really any wonder that it takes time and having to bear witness to her father’s death (a direct result of Joffrey and Cersei’s betrayal and manipulation of Sansa’s trust) in order for Sansa to reject everything which she has ever known? Sansa Stark is, after all, like every Stark, a wolf. But a lone wolf is an anomaly, and Sansa is the ultimate pack animal. It’s just that she finds herself suddenly and cruelly without her pack, alone in a tumultuous world, in which every privilege with which she was endowed is newly revoked.

Perhaps if Sansa had responded to her father’s execution and the immediate branding of the rest of her family in a more ambivalent way, it would be easy—and even right—to condemn her. But Sansa—despite being surrounded by enemies, brutally beaten by her captors, and wedded to a member of the family responsible for her own’s downfall—does not waver in her hatred for her former heroes. Oh, Sansa continues playing the part of loyal subject, but inside she rages against the injustice and takes every opportunity she gets—even when those opportunities only take her further and further from the idea she once had of who she should be—to escape Cersei and Joffrey, and reunite with her family. And yet, despite her shattered dreams and despite having to rid herself of the world view she’s always held, there remains in Sansa an inherent humanity and an ability to relate to other people that few of the other, more-loved characters have. This is what gives us hope for Sansa and demonstrates a resilience that is essential to survival. Sansa has long known that it is a woman’s job to yield, and while that might not seem like the most powerful tool (certainly not in comparison to dragons!), it is a quality which benefits Sansa as she is entrenched in the enemy camp, with no apparent allies at hand. Sansa might not—and indeed must not—exhibit external strength for now, but that is fine, because she can use this time to gather her resources and plot her next move in a terrifying world.

The problem with Sansa Stark is not that she’s weak or sniveling or that her more traditionally womanly attributes put her at a disadvantage compared to the other characters. The problem with Sansa Stark is that she bought into a world that was nothing more than an illusion; she was born into a position of privilege that turned out to have a crumbling foundation. The problem with Sansa Stark is that she is just like most of us, and so we hate her. The reality is, most of us live entrenched lives, relying on foundations and systems that we’ve been familiar with since birth, trusting that the institutions will stay strong, hoping that we will never need to start all over. Most of us aren’t iconoclasts like Arya, combatting the injustices of the patriarchy from day one. Most of us aren’t dragons like Daenerys, possessing inner gifts that allow us to transcend any limitations that the rest of the world endures. Most of us are trying to do the best we can in an ever-changing world while also trying to uphold the values and ideals we’ve always held close. Arya and Daenerys are who we want to be, but Sansa is who most of us are. And that’s just fine. Sansa might not ever be queen. Sansa might not ever exact revenge on those who killed her father and mother and brother. But Sansa is doing something just as remarkable for the world she navigates: she is surviving. And every day that she lives, she learns more about herself and about what is important and what is superficial. So, no: Sansa might not be a hero, but the Seven Kingdoms has enough heroes. Most of them die. And yet Sansa survives.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like