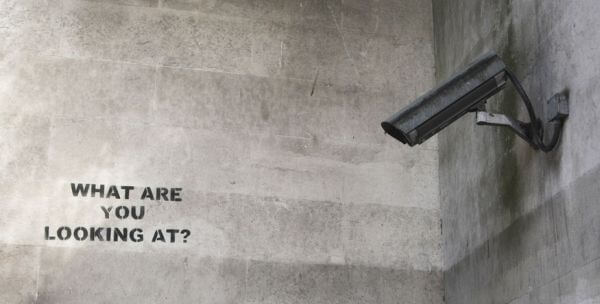

Trying Not to Pay Attention to Banksy

Banksy has been putting up pieces around NYC for two weeks now. Some seem to be sticking around for a while, others vanished or were “defaced” within hours. At least one will stick around forever, or for as long as YouTube’s servers will stick around. For most intents and purposes, probably forever. The probability of YouTube’s servers going kaput is very, very low–but who knows, it’s totally possible that YouTube could crash. Irrevocably crash. And then what would we lose? What do we lose when a Banksy piece is “defaced” or “violated” or erased? Well, for one, we lose the hyped, mob-like urge to see a Banksy. But, maybe it’s also good to consider what we gain out of a “defaced” Bansky. In that light, the “Omar” tags stand as the possibility of our participation with capital-A Art (or with someone with as much cultural currency as Bansky) beyond the classic Art/Spectator binary you get in a museum. He doesn’t want us to only look. I think he wants us to be doing something beyond that.

It doesn’t surprise me that when Banksy posted the YouTube video of two soldiers shouting “Allahu Akbar,” one wielding a shoulder-buttressed rocket launcher, one pointing towards an unidentified flying object, and firing at that object–which turned out to be Disney’s Dumbo–no one really talked about it. People are paying attention to the Red Hook Nightwatchman, pay-per-view in East New York, original Banksy canvases for $60. But you can’t Instagram a video (at least in the way Instagram is supposed to be used–not as a reblogger but as a tool for capturing spontaneity–a state of being which is opposed to being captured and contained), you can’t pose with a video, and you can’t say “I was there, before it got erased, I had an experience.”

My favorite piece of Banksy’s, so far, is this YouTube video, because it’s not spontaneous, but a different perspective on street art. Why, out of his 30 day residency in NYC, did he post something in the internet? In a way, it’s a kind of digital graffiti; it’s easy to forget that if all the global data centers (and that includes our personal devices) were to crash, the internet would disappear. You’ve seen what our reaction to this catastrophe looks like, and you’ve also experienced it. When I see it happen, it’s a bit sadistic, but I really enjoy watching someone freak out when their phone’s 4G and WiFi capabilities, for whatever reason, fail them. It’s uncanny, because we live with the comfort that radio, the internet, and cloud data don’t ever fail. It doesn’t seem possible that we can’t check our text messages walking through Prospect Park today, even though we did yesterday. The internet exists so long as the physical servers are up. It’d be much more intense than a black out, I think. You lose the lights and phone lines in a black out, yes, but you do not lose the immediacy of contact with those around you, or those that seem to be around you because they’re in your phone, typing. The real joy of Banksy’s project this month is his play with digital and concrete forms of recording with a genre that shouldn’t ever be permanent, but are.

So, I have been trying to avoid following Banksy’s website, and the press coverage when a new piece arrives. We are supposed to be surprised by his work, to be caught by the incredulity of a truck “bursting” with stuffed animals out of its wooden slats. To be shocked that our stream of life is interrupted. All of the hub-bub about Banksy’s pieces being defaced–and how that is a supposedly awful thing–might do harm than good to Banksy’s contribution to public conversation and consciousness. It makes him precious. He is work is not precious. His work is not something with which to pose your baby. It is also something not to merely consume, to regard for a minute and then plunge face down into your Facebook menu the next.

And, yes, the YouTube is not the most radical thing he has ever done; YouTube is owned by one of the largest, if not the largest, internet companies around. But it raises a question about the illusion of permanence in an increasingly mediated world. The several strands of Banksy’s city residency–the gallery-website, street workshops, YouTube videos–all help to raise this question about our involvement with the ephemeral, our desires to painstakingly preserve every moment of our lives in our social media. Fundamentally: why we want to exert so much control. I mean, isn’t the most ideal preservation of Banksy’s art for it to be surrounded by how we participated around him, so in the future, we could see between the gaps of others ideas, transformations throughout time? So, maybe “Banksy” wants us to be a little bit like “Banksy,” like rip shit up.

You might also like