Courtesy of A24

John Carroll Lynch on ‘Sorry, Baby’ and The Scene of The Year

The legendary character actor discusses how he stole the show with humanity in the new A24 film 'Sorry, Baby'

The most complicated, heartrending scene in writer/director/star Eva Victor’s melancholy, stunningly soul-nourishing debut Sorry, Baby comes an hour and fifteen minutes into the A24 acquisition. It begins with a panic attack when Victor’s protagonist Agnes starts hyperventilating behind the wheel. She pulls off to the side of the road in front of a sandwich shop in the unnamed Northeast liberal college town she teaches in, and has the good fortune to park in front of a restaurant operated by Pete—played by the great character actor John Carroll Lynch—who immediately drops his gruff New England demeanor and talks Agnes down with empathy, a patient ear, and the perfect sandwich.

It’s as good a metaphor as any for Lynch’s career, an actor who has long served as a safe harbor for directors who need to briefly inject a measure of calm, and slow their films down for a few minutes. His power is upsetting expectations. The Boulder, Colorado native is a hulking 6’3, and is in his early 60s now, but the thick-necked and nearly bald actor hasn’t aged a day since he popped on screen as Chief Marge Gunderson’s tender husband in the Coen Brothers’ classic Fargo nearly 30 years ago in 1996.

Since then, Lynch has logged hundreds of credits on IMDB, all over the spectrum, from marginal to celebrated. He’s acted for legends of American film, including Martin Scorsese, David Fincher, and Clint Eastwood. He directed a film of his own, starring the late great Harry Dean Stanton and David Lynch’s tortoise (and David Lynch, no relation). On television, he’s done one-episode stints on some of the best-oiled serial machines and shows you’ve never heard of, had mini arcs on prestige totems, and most notably, played Drew Carey’s brother for seven seasons. Because of his proportions, he can, and has, credibly played suspected serial killers and literal nightmare clown monsters.

But what makes Lynch a distinct character on the American landscape is the inherent warmth and decency that emanate from his crows feet and smile lines when given a script that let’s him flex his humanity, the at-command welling of his eyes and the quiver in his baritone that indicates there is a big beating heart beneath what appears to be red state packaging. He is the perfect avatar for Sorry, Baby, a film about harsh realities and callous cruelty of individuals trapped within the chrysalis of immutable institutions, that floors you precisely for how optimistically it looks at the rest of the intimate community tight-knit around its wounded protagonist, and how tender that world handles her when she needs it the most.

Lynch is on screen for just under five minutes, but they represent the best minutes I’ve seen in a theater this year, so with Sorry, Baby playing at BAM (and going wide on July 25th), it was a pleasure to have some phone time with the actor to discuss his experience with this great movie, and where it fits in the context of his incredible career.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity (and to make the writer sound like less of an asshole).

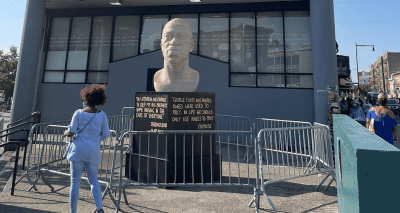

BKMAG: So, because this is Brooklyn Magazine, do you have any ties to the borough—or to BAM in particular—where Sorry, Baby is playing right now?

John Carroll Lynch: Well, I mean, first of all, I love BAM. We go there all the time. We see a lot of plays there. My wife has performed there. We have friends who performed there. I saw that fantastic Medea with Bobby Cannavale and Rose Byrne. I thought it was terrific. But my daughter is in Fort Greene, so we’re over there all the time. Love that neighborhood.

How did the role of Pete come to you?

It was an offer from the filmmaker, via a wonderful note. I read the script and I thought it was terrific. I thought it was funny, and it didn’t pull punches in terms of how none of us can really speak about anybody else’s trauma with any effective compassion or empathy, especially in corporate or institutional settings, and how we’re all frightened to talk about it.

Was the role written specifically for you? Because it feels like it.

I mean, one is always told that one is the first choice, but that doesn’t mean that is true. But I really liked him. There were two scenes in the piece. I thought Eva was extremely wise to cut one of them. It was lovely material. I liked being a person who can speak to trauma from a human place.

Were there rehearsals for the scene?

Not really, no. We rehearsed on the day. We didn’t rehearse together before that. Eva was quite busy, as you could imagine, with pre-production and with all the things that one has to do as a director, and then to act. But we had a good amount of time, particularly sitting on the little concrete parking spaces. And it was beautifully shot. I think that the DP and Eva worked beautifully together.

Did Eva do anything to prep you before coming to set?

Eva sent me a letter that was quite descriptive of who she thought Pete needed to be. Eva was specific about his spirit. We spoke about the idea of him having a New England accent. I thought it was important in terms of class. It’s really a thing in New England towns like this. This took place in Maine, and I had a good Southie accent, so I leaned on that, although it’s not correct for Maine. But a lot of people from Boston move up to Maine, and they’re never fully at home. If they move up to Maine… Mainers are quite territorial when it comes to that.

Anyways, I know that we agreed that there should be a difference in terms of social status between Pete and Agnes. There are these gaps in places like Middletown, Connecticut, or even New Haven, where these universities sit inside towns that don’t really coincide. I liked that aspect of their meeting as a crosscurrent, and Eva did too, so I guess that was prep.

In the letter Eva sent, what was the general idea of the character that was conveyed to you?

Well, I think it’s the only time that Agnes really speaks to someone who isn’t her best friend, to some degree, about what’s happened to her. And she speaks to him, not in some corporate setting, where there’s a necessary insurance component to it. When dealing with people about her incident throughout the film, for the most part, there’s always an ulterior motive, as there is with the women in the scene where she tries to alert the university, as there is with the doctor in the hospital scene.

Pete has no ulterior motives. And that was something that Eva mentioned in the letter. He has experience with panic attacks and trauma from his son, so he has a feel for it. So he’s responding to her as a human being with experience in the area. When he says, “Are you okay in your house?” He’s asking her two questions. One is, “Are you okay? Are you still living with the abuser or not?” And the other is, “Are you going to be okay by yourself in the house?” And she says, “I have a cat.”

His only agenda is her care, and he does it in a really human way—something that we’ve done as people for each other forever. There’s an old joke about Jewish holidays: “They tried to kill us, they didn’t, let’s eat.” I think that to some degree, that’s what the sandwich is: I can’t take away your trauma, I can’t fix anything for you, but I can make you a sandwich. That’s what I can do, and I can treat you like a human being. But Eva also wrote somebody that isn’t a saint. He’s an asshole. He’s a bit of an asshole. So I like that about him, too.

As a Jewish person, I appreciate that sentiment. Speaking of the sandwich, aside from the Calabrian Chilies, do you have a sense for either what was actually, or theoretically, in the sandwich?

Oh, yeah. I know exactly what was in the sandwich. There was a longer description in the scene—Eva wisely cut that, too. It was essentially an Italian-style sub-sandwich, but the Calabrian Chili was really what put it over the top. It was his personal touch. I’m not sure if it’s still in the scene, but at one point he says, “It’s really expensive.”

Yeah, he does.

It’s him telling Agnes, “I want you to know that I’m in it to win it, when it comes to sandwiches.”

Aren’t we all. Now I need to make that sandwich. Did you have any life experiences that informed how you handled the scene and approached the character?

Yes. It’s one of the reasons why I’m drawn to scripts like the one Eva wrote. I’m a 61-year-old man, and I grew up in one world where in high school, I was given a really strong impression of misogyny and entitlement. It was not questioned or questionable. And I certainly didn’t question it. Over the course of my life, I’ve seen more and more the arc of the journey of women in our culture. When I see a script that drives directly towards this subject in such an artful way with someone who’s really doing the work, I want to support that effort because, to some degree, I’m culpable in the society that I live in. I want to be part of the medicine, not part of the poison.

And here’s the thing, you can also play horrible people and be part of the medicine. I’ve done that, too. Played plenty of terrible people. But it’s much nicer to play the part of aloe vera as opposed to the match that burns the skin. It’s much nicer for me. I like that better.

One of the most interesting moments in the entire film is the one that sets off Agnes’ panic attack, which leads her to your character. Do you have any insight as to what exactly she’s responding to?

I don’t have an insight to it. It doesn’t need to be anything. There’s a lot of great stuff that has been written about PTSD. And it doesn’t need to be much to have that effect. As Agnes says in our scene, “It happened three years ago,” and Pete goes, “Well, that’s not much time.” And that’s true. Agnes is going to be digesting this thing for the rest of her life. The fact that it comes up in times that she can’t predict is part of the trauma.

You’ve worked with some of the greatest directors who have ever lived. You’ve directed your own film. You’ve worked with other first-time directors on indie films. How would you compare or evaluate the brief time that you got to watch how Eva ran the set?

The team was put together in a really beautiful way. Eva was so well-supported. I have a picture of the first assistant director, the cinematographer, and Eva talking about what they were shooting, standing in front of that beautiful vista of the wetlands. I sent it to my wife and said, “Filmmakers at work.”

The spirit of a set flows from the relationship between those three people. I so appreciated their synchronicity. Eva told me they’d been working on the material on their own for a long, long time. So they had done a lot of prep beforehand. And if you’re going to make your first movie, you should try to make it as many times as you can before you actually have to make it, right?

Their understanding of the material from the outside, especially when it’s something so intimate, their ability to stay inside the material when they needed to, and to create distance to get the right shots when they needed to, especially through the editing process, where you can get really precious with stuff if you’re not disciplined enough—it was all spot on. Eva has some of that preternatural wisdom to start with as a filmmaker, which is great. The point of view is so specific as a writer, and Eva is also an excellent actor, which, all of those elements in the same package, is, needless to say, impressive.

You’re great in every role, but in my opinion, your superpower as an actor is playing gentle. Is there any secret that you ascribe to conveying gentleness on screen?

I would just say that I think sometimes gentleness is portrayed as weakness, and I don’t think they’re the same thing.

I’ve had the wonderful opportunity to play men in certain circumstances, certainly in Ballard right now on Amazon Prime, but also in Fargo, in which the gentleness is about caring for someone you love. And that doesn’t come from weakness. It’s written in the script that it’s effective, just like it is in Sorry, Baby. Being gentle, being kind—I’m a big believer in the power of kindness as a person. And one of the things I love about Fargo, for example, is the thing that makes Marge so powerful is her common decency. She’s not the most physically powerful person in the room by any stretch of the imagination—although she’s carrying a child while she’s at work, that’s pretty impressive. But what she does, mostly, is she has a moral compass that she follows with humility and kindness.

And I think that’s a very powerful thing. It’s powerful when people are truly kind. And I think that also has to come from a place in which the material doesn’t flinch from the darkness, like in Sorry, Baby. So if my “superpower” has been gentleness or kindness, it’s because the worlds that kindness has been exhibited in don’t flinch from the darkness. And so it shines like a little penny in the dirt, if that makes any sense.

You might also like