Liev Schreiber (left) and Zoe Kazan in the revival of 'Doubt'

John Patrick Shanley stares into the darkness and asks ‘how can I enjoy this?’

A conversation with the award-winning writer about 'Doubt,' stolen laundry and his biggest regret about 'Moonstruck'

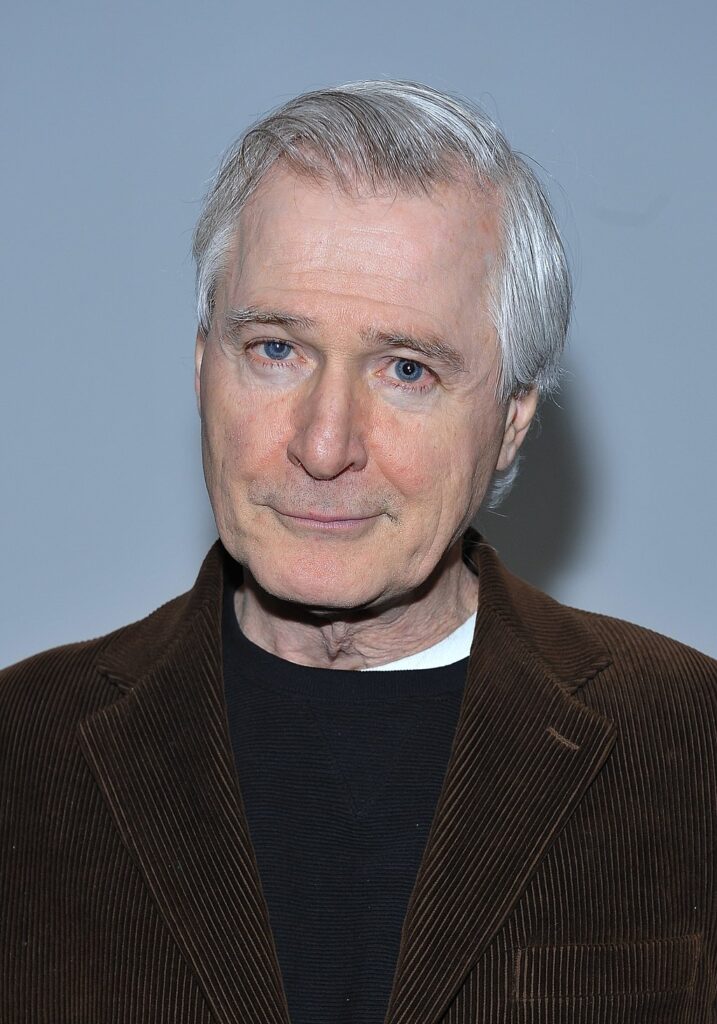

John Patrick Shanley is trending at 73.

His play “Danny And The Deep Blue Sea” was revived last winter at the Lucille Lortel Theatre in the West Village. His Tony- and Pulitzer Prize-winning play “Doubt: A Parable” was revived for the first time on Broadway in March, and his latest play “Brooklyn Laundry,” starring Cecily Strong and David Zayas — a romantic comedy with a dark side — just completed a run at New York City Center Stage I.

But when we spoke before nominations for the 77th Tony Awards are to be announced on April 30, Shanley was more interested in weighing in on the broader state of the world.

“There are a lot of really terrific people in the world,” says Shanley. “But they are not at the microphone at this time.”

It’s not that Shanley is prone to despair. He remains a realist, with a wry filter. Take “Doubt,” which, despite being about sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, is an accessible play. And, to hear Shanley describe it, mostly a comedy — albeit with moments of breathtaking drama. Shanley knows how to make the most sour of topics palatable.

To the playwright, bringing joy to despair comes naturally. “Contradiction is inherent to the human experience,” he says.

Shanley’s three shows have recently closed for the season and only “Doubt” is eligible for a Tony (in the Best Revival of a Play category), as the other plays were Off-Broadway, and the Tonys only awards Broadway shows.

Brooklyn Magazine spoke with John Patrick Shanley about working on “Brooklyn Laundry” and “Doubt” at the same time. He talks about injecting heavy subject matter with humor, and directing Timothée Chalamet in “Prodigal Son” before his breakout role in “Call Me By Your Name.” And naturally we talk about “Moonstruck,” the 1987 Oscar-winning, Cher-starring juggernaut that he wrote.

Shanley (Photo by Sam Santos/George Pimentel Photography, CC BY 2.0)

How did you splt your time between the revival of “Doubt” as you were preparing “Brooklyn Laundry?”

I was involved during the first week of rehearsals for “Doubt” before I went over to “Brooklyn Laundry” and started rehearsing that. And then I came in for their first readings, first previews, things like that. When Amy Ryan took over for Tyne Daly, I came back to see what was going on there, to give some notes.

“Doubt” has the subtitle “A Parable,” but most parables illustrate a simple lesson or moral. Is your point in calling it a parable that child sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church is anything but simple?

I’ve always been fascinated by the Biblical parables. When I was a kid growing up in Catholic school, the sermons on Sunday were almost always based on the Bible and very often parables. I always felt after the priest explained the meaning of the parable that he was wrong. [Laughs.] It didn’t matter what the subject was, I really would have liked to go back and forth with the priest about it. It might not mean what they think. It might be something quite different. I was concerned during the original production of “Doubt” that it might be taken simply at face value, as a “ripped from the headlines” kind of play. There was more to it for me than that. I wanted to invite the audience to think twice about why they were hearing the story and why they were experiencing the story.

I found myself siding with Sister Aloysius (Amy Ryan) because sexual abuse in the Catholic Church is rampant. But I had to remind myself that the Sister’s morals are like a hammer, and to her, everything’s a nail.

I think that the greatest conflict that people face is internal. And that all the valuable work an individual living on this earth can do is internally. There are actions we perform externally that are important, but they are completely powered by the internal struggle that takes place first. Any thinking person is going to have doubts about their judgment and have to revisit first impulses. We revisit first impressions so we’re not simply reactionary creatures, but thoughtful people.

That’s something audiences can really chew on even outside the context of “Doubt.”

I think that in general in the world today, but also throughout history, a good piece of advice would be, “Hey, can you lower the temperature? There’s so much noise going on. I can’t reason with you to a place that might be constructive.” Always the temperature is turned up high on social media and all of that. When I was a kid, there was the Red Scare, and people were just histrionic about that. It does seem like there’s always something like that going on, where people have to win no matter what, and morality and judgment go out the window, along with mercy and charity.

Liev Schreiber, who played Father Flynn, seems to find himself performing in stories about abuse like “Doubt.” He was also in “Spotlight” and “Ray Donovan” has those storylines. Do you know what draws him to it?

I think that Liev’s certainly a prime candidate to play Hamlet. The debates that go on inside of him are sufficient without my adding to it. He is an incredibly intelligent and thoughtful actor with tremendous command over his abilities, which leaves him with, “Well, I could do it this way or I could do it that way,” ad infinitum. He had to wrestle that internal beast to the ground within a four-week rehearsal period because he had to go out there and make choices. And he does that, but it is not easy for him. Rehearsing is not easy for Liev, not because he can’t do it. It’s because he can’t go through the process by making up his mind in the beginning. He has to struggle. That’s his nature.

I didn’t know “Doubt” would be so funny. Will you talk about using humor to talk about something so dark and slippery like the persecution of gay priests and child sexual abuse in the church?

I guess my internal directive for life is: “How can I enjoy this?” And so that extends to, like, if I break my leg, how can I enjoy whatever the heck is going on? So no matter what I’m writing a play about, there needs to be joy in it. That needs to be an element of it because if it is not in there, to me, it is not a full human experience. I don’t like to give the notion that only one emotion is permitted within the bounds of a particular play.

I read that “Brooklyn Laundry” is partially inspired by an experience at your local laundromat. A customer walked off with your bag of clothes and sheets and you negotiated with the laundry owner how much credit you should receive.

Ultimately, I probably should have paid them because I made a play out of it. It is to me an endless source of speculation and amusement: who the heck took my laundry and are they wearing my clothes and sleeping on my sheets?

Timothée Chalamet starred in your play “Prodigal Son” in 2016, just before his big break in “Call Me By Your Name.” What was it like directing him as a version of yourself?

Oh, he was great to work with. I mean, he was so obviously abundantly talented and completely committed to excellence. And at the same time, having a grand old time being an actor. That combination of things made it a joy to work with him. As for Timothée playing me, various people have in different ways, Tom Hanks in “Joe Versus the Volcano” does some subtle mannerisms that I might do, and Kevin Kline in “The January Man” is basically doing my accent, so I’ve gotten used to it. When I first got exposed to actors, I had a very heavy Bronx accent, and they would mimic me. I would get angry thinking they were making fun of me. Then later on, when I began to understand how an actor is an actor, and that this memetic ability is a way of understanding people, and then it just became kind of fun.

I have to ask some “Moonstruck” questions. Why did you set it in Brooklyn Heights?

It exemplifies the kind of grand old New York family that inhabits a building that’s like a mansion, and yet, Cosmo [played by Vincent Gardenia] has what appears to be some kind of modest job. But in fact, plumbers do make a lot of money. I also always ask myself the question, “What am I gonna film?” I want it to be beautiful. I’m not gonna put it somewhere where I don’t find things that I find beautiful.

What was it like collaborating on the movie with director Norman Jewison?

Norman was incredibly generous and great fun. The first thing that happened was when he optioned the script that I’d written, he asked me to come to Toronto. We sat down in his office, and he took half the roles and I took half the roles and we acted out the whole thing. So I played a love scene with Norman the first day that I met him. And I played Ronny Cammareri [played in the movie by Nicolas Cage], so he was Loretta Castorini [played by Cher]. One of the great regrets of my life is that somebody didn’t film that. [Laughs.]

You might also like