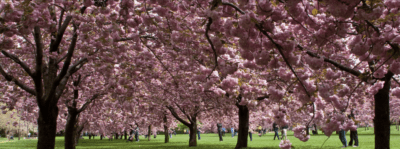

Installation view of Christian Marclay: Doors. Brooklyn Museum, June 13, 2025-April 12, 2026 (Photo by Paula Abreu Pita)

Christian Marclay Debuts ‘Doors’ at The Brooklyn Museum

Christian Marclay's entrancing new film 'Doors' premieres stateside in the Brooklyn Museum's newly installed Moving Image Gallery

It’s a cold, damp mid-June Thursday morning off Eastern Parkway, but I feel warm, at peace, in a sweater on the fifth floor of the 200-year-old institution, Brooklyn Museum. Multiple end-of-the-elementary-school-year class trips are here, children walk in large, loose clusters, momentarily cowed and awed by the grandiosity of the museum’s atriums and rotundas, the endless hallways lined with sculptures and wall-mounted canvases just slightly larger than their standard screen of choice. Early-20-somethings, presumably students, lay out on benches, talking about art excitedly, or sketch on their spiral pads, dreaming of displaying their own work here someday.

The fifth floor is where the reinstallation of Brooklyn’s impressive, eclectic American art collection spans eight galleries, and now houses the Moving Image Gallery, where I’ve just seen a preview of the artist Christian Marclay’s Doors, an installation that will run through April of 2026. It is the headline, but not alone amongst the exciting work being done at the museum. The fifth floor has been reimagined with gallery walls painted mauve and ocean blue, and there is a special exhibition dedicated to gold. I spend some time standing below a guided meditation by the artist Tricia Hersey over an ambient hip-hop beat, which plays softly from a speaker in front of an Alma Thomas canvas in an exhibition room painted royal purple, with two caramel leather couches sitting on a rug at the center, making the space feel more interactive.

This feels intentional, a mission statement of unapologetic outer-boroughness. Paintings are densely arranged, like a friend injecting life into every square-inch of wall space in their studio apartment. Enormous three-year-old gender fluid tapestries from the Navajo artist Nanibah Chacon exist alongside 150-year-old luminist landscapes of Lake George painted by dead white male American masters. It’s a modern and classic equation, playing with this tension floor by floor and room by room, turning its blended identities and eclectic collection into its strength as it enters a new era in team, in design, and in layout.

Installation view of Christian Marclay’s Doors (Photo by Paula Abreu Pita for Brooklyn Museum)

So, Doors can be taken both figuratively and literally, in its subject and in its positioning, as a part of a new epoch for Brooklyn Museum. The work was co-purchased with the Hirsch Museum in DC from Marclay, the 70-year-old Californian and Swiss artist with a pop sensibility. Because it’s the introduction of a new gallery on the fifth floor, curator Kimberli Gant and the Museum braintrust wanted to make a splash with its debut. “Christian is a major international artist. It’s something to get people excited to see here,” Gant says. Marclay’s project as an artist is to recontextualize and call attention to the underappreciated ephemera of life: old tech like vinyl, telephones, clocks, and, of course, doors. “[Christian’s] work is always thinking about outdated technologies and media that we at one point began to take for granted,” Gant herself notes.

Marclay made one of the most written about and sought after works of modern art this century with 2010’s The Clock, a 24-hour collage that was first shown in New York at the Paula Cooper Gallery, then toured globally. It was obsessed with keeping time. The New Yorker called it “an addictive masterpiece”. It mines the history of cinema, with a synchronized eye on the hands of the titular object, tracing a day on film. Like every city resident who was conscious in 2010, I had read and heard much about the ubiquitous exhibit, but never made it out for a marathon screening. I assumed it was experimental durational cinema. That changed when The Clock returned this year at MoMA, and I had the experience shared by so many who have seen it: popping my head in to catch a few minutes, only to end up staying a few hours. It’s because The Clock is the opposite of a long, contemplative sit—it absolutely moves.

Marclay is a gifted synthesizer of pop art. Think: Girl Talk with an MFA, a master collagist, and a Walter Murch-level editor. The literal hours pass as you watch Richard Dreyfuss juxtaposed with Monica Vitti, and it provokes many literal and abstract connections to the nature of film, routine, memory, and the distinct rhythms of daily life.

Doors debuted in London in 2023 and follows The Clock, Marclay’s first work since that breakthrough, shifting focus from time to portals of entry and exit, using the same style of visual language, composed of characters in film entering and exiting rooms through all types of thresholds: into and out of elevators and prison cells and houses and buildings, with some notable variations. Marclay uses the abbreviated length and the change in focus to play with the rules he created in his previous work. It is obviously not sequential, so certain clips can recur like phrases of music in a symphony. And they do, which contributes to a seamless loop quality for viewers only tapping in for 10-20 minute spurts, while rewarding those who may choose to watch for a full hour. There was criticism of The Clock, that its reliance on pop film to compose its day can shake savvy film nerds out of its spell and turn it into a game of trivia as they attempt to identify actors and films. For the most part, though Marclay is employing giants and legends in Doors (like Lino Ventura, Jack Palance, Courtney Cox, Bill Pullman, Christopher Walken, Audrey Hepburn, Jack Lemon, and more), the references are mostly less overt, and I personally didn’t bump on it.

Installation view of Christian Marclay’s Doors (Photo by Paula Abreu Pita for Brooklyn Museum)

Marclay’s latest cinematic patchwork is surprisingly playful. It takes what seems like a rote and straightforward concept, fills its runtime with endless possibilities and permutations, and leaves the impression it could go for hours on. It’s perhaps an even more impressive display of Marclay’s skilled editing. The film flows seamlessly, transitioning naturalistically through its clips. Weathered and scummy basements open into elegantly appointed penthouses. Characters step forth in color and emerge in black and white, they’re speaking French on one side and English on the other, they look through keyholes into different films without the viewer ever feeling the stitches, putting genres and eras and formats in conversation with each other to point out the lie of editing in constructing a visual story. Long takes are juxtaposed with incredibly brief ones. The rules change: a character can run through a door, and the built expectation will be a cut to another character entering a room in another film, but the prior scene continues, which is disorienting but holds your attention. The intention seems to be to continuously distort a time signature you’re never quite allowed to settle into.

It’s a taxonomy of doors, keys, and locks, in all different styles and shapes you only begin to notice and classify through sheer exposure. Sound is also employed as connective tissue, with effects and scores from one movie bleeding into the next, and Marclay appears to have amplified the foley in the films, making each squeak of hinge or slam of latch pronounced to dramatic volume, further focusing the viewer’s attention on the physical acts of opening and closing.

The piece is effective in deconstructing doors as liminal spaces, as props, as provocations, as ideas employed to wildly diverse effects in film. Characters brace themselves for the situation, the new world on the other side, the violence and speed with which you lock a door, how you distractedly rummage for keys, how quickly you run towards or away communicates everything. At one point, a woman pauses, and in her measuring, you feel the great weight ahead. Over and over again, the way a character interacts with a door silently tells so much about whoever or whatever is waiting for them there, what might have once happened in that room, who might’ve once lived in it. The work is an endless loop of waving and cresting that builds the anticipation of entry, the relief of exit, and vice versa.

And you watch it all in Brooklyn Museum’s Moving Image Gallery, which was constructed and custom-designed with Marclay to stage Doors to his specifications (particularly the sound quality). “After we painted it out and everything, [Christian] said, look, we have a standard, but you have to also play a little with what your space needs, so we did, and the result is fantastic,” Gant adds. It will remain as a fixture of the Museum’s fifth floor going forward, with plans to replace it with other “moving installations” following the end of the film’s run in the spring of 2026.

But importantly, it’s just so much damn fun. There are several loving, dedicated genre pastiches for red meat film nerds: hitman montages, horror montages, noir montages. Because of its focus, Doors is constantly in motion. It can wash over you on a summer afternoon for a few minutes, or you can enjoy all day if that’s your preference, engaging with it on a deep level of study and thought, or just taking it in and waiting for the surprising associations to jump out at you.

You might also like