Artist and illustrator Sean Qualls on collaborating with Questlove for ‘The Idea in You’

'I want to make work that elevates humanity': The artist discusses the new book, his fine art and creative career

Like what you’re hearing? Subscribe to us at iTunes, check us out on Spotify and hear us on Google, Amazon, Stitcher and TuneIn. This is our RSS feed. Tell a friend!

Sean Qualls is a Brooklyn-based artist, award-winning children’s book illustrator, author, and occasional DJ. He’s also a dad. Among his better-known works are the illustrations for “Emmanuel’s Dream,” a Schneider Award recipient written by Laurie Ann Thompson, “Giant Steps to Change the World,” written by Spike Lee and Tonya Lewis Lee, and “Before John Was a Jazz Giant” about John Coltrane, a Coretta Scott King Illustrator Honor, written by Carole Boston Weatherford. His latest book is a collaboration with Roots drummer, Questlove. Yeah, that Questlove. It’s called “The Idea In You.” It’s a truly charming, delightful children’s book about finding that first spark of creativity and what to do with it.

You can also see Qualls’ art on display now through November 10th in a solo exhibition called “Inner Victories” at Established Gallery at the intersection of Flatbush and Sixth Avenue. The title of the show explores the idea that private victories precede public triumphs. And man, isn’t that true?

“As an artist getting into the studio and making your art, it’s the essential quality behind everything. It’s what we do in private,” Qualls tells me. “We have to put in the time in our private lives in order to sort of have the personal rewards that we’re looking for. Anyone we really think of, from Beyoncé to whoever, it’s all the unseen hours that one puts in eventually comes out.”

His work across the board, both nonfiction and figurative, leans into notions of race and identity and the intersection of history and mythology. “I want to make work that elevates humanity,” he says.

Qualls, who is also, full disclosure, a pretty good friend of mine, joins me on the latest episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast.”

The following is a transcript of our conversation, which airs as an episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast,” edited for clarity. Listen in the player above or wherever you get your podcasts.

I want to start with a disclaimer that we do know each other.

Yeah, it’s still an honor. I understand the challenges of knowing people and being asked to sort of exploit that, whatever you do.

Well, no, no, no. Not exploiting. Even if I didn’t know you, I will say you have passed the threshold required to be a guest on this podcast. In fact, I think the threshold was higher because I know you. You illustrated Questlove’s most recent children book, “The Idea in You.” This is his second I think?

It’s actually his first. I think he did a middle grade something or other in terms of a proper picture book in the vein of Dr. Seuss and all that. This is his first, so it’s his debut picture book.

He has like 500 other books and he’s working on two movies right now on top of his Roots gig and the Jimmy Fallon show. The breadth of his work is just staggering. Did you pick up anything in working with him in terms of that range and depth of creativity, work, whatever it is?

I get offered to illustrate other people’s books quite often, which is also obviously an honor. In the case of Questlove, with everything you just said, it is so true and I just wanted to be adjacent to that. His vast knowledge of music and his appreciation of culture, his take on creativity and being in the world and being so multidisciplinary. I just really wanted to be adjacent to that. Then on top of that, he’s a huge music nerd as we both know.

As are you, as people may not know.

And then he is also from Philly. I grew up in New Jersey, very close to Philly. My mother’s from Philly, her family’s from Philly, so we have that in common. So I felt like there was enough sort of linkage that I definitely wanted to be adjacent to him in some capacity by doing this book.

Who have you turned down? Who reached out to you where you’re like, “nah”?

One that I turned down and who I love, I just didn’t have time, I turned down a picture book from Rebecca Walker. She’s really amazing, and it was really hard because not only did she want me to illustrate her book, but she said, “In reading about you, I love the fact that you mentioned growing up with your mother and your sisters and the women in your life and feeling that connection.” It was really hard. I’ve admired her for a while.

So how did this come about? Did he reach out to you, came through the publisher? How did it work?

Through my agent and the editor at Abrams, Emma Ledbetter, had reached out to her. I’m not sure exactly how it came to them. I think Questlove had a contract with them to do a set of books, and this was one.

It’s called “The Idea in You.” It’s about that first spark of creativity and leaning into that star of an idea. He’s fascinated by this idea of creativity, he wrote a whole book about it, “Creative Quest.” So is this the children’s version of his book on creativity?

That was always my take on it, and I had read that book when it came out. I was really excited about it. And one thing that I really got from that book that I love, I think he had started meditating then and he was very into doing these very brief meditations. The idea of like, oh, I have a minute, or I have three minutes doing that brief meditation. And back when I was in my 20s, I had meditated a lot more. Now, I don’t know, my life’s busier and everything. I just got into that sort of idea as a springboard to feel your creativity in the moment. Just shut out all the noise from the world and go internal for a minute or two.

What was it like working with him? I can’t imagine you were able to have too much access to him. What was the process?

It was a lot of back-and-forth between me and the editor just regarding the manuscript at first, because the manuscript changed a lot, and then I think we did meet all together, Questlove and some of the people he works with at his writing team. We met together and then we sort of talked more details about it and then I came up with a set of sketches and passed those on to Questlove via my editor. My editor gave me feedback. I think the team gave me feedback. At some point I also did a sample piece just to give them an idea of what my vision for the book would be. So once the sketches were finally approved, I moved on to final artwork. They were very open and excited about my art, which was so great. I felt like I had a lot of freedom to create images that I felt evoked what he was trying to evoke in the text, and not only that, but sort of reach back into the “Creative Quest” book in some of the ideas that I found there as well.

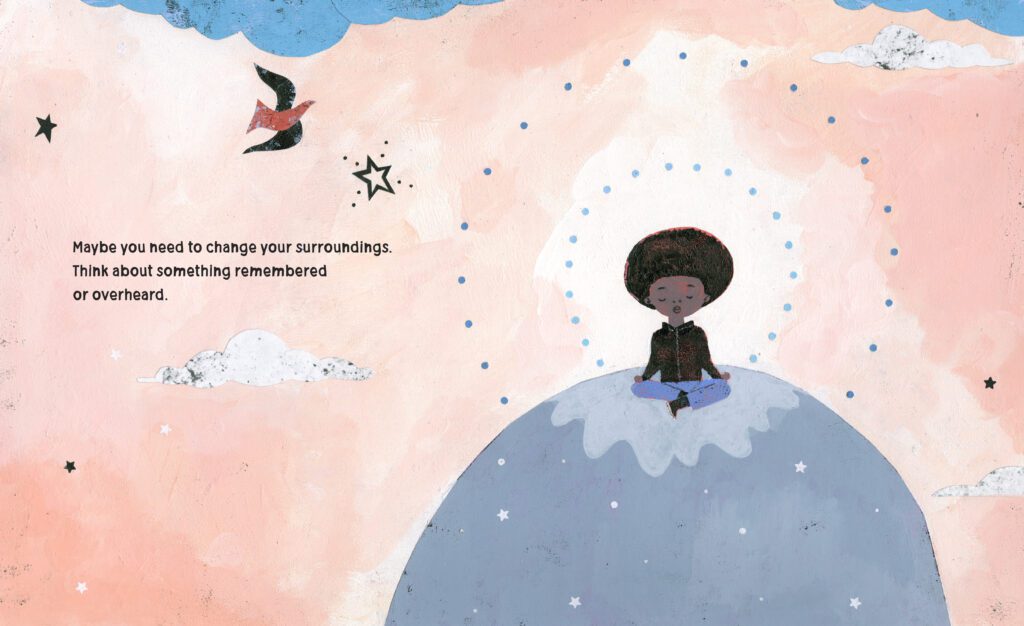

A spread from “The Idea in You,” by Questlove, illustrated by Sean Qualls

You didn’t have to kill any darlings? There were no things that you were just really hoping would go in that they were like, “no”?

The boy meditating on the mountain top was one of images I really wanted, and they went for that. Some of the stuff that got killed I think probably wasn’t worth fighting for.

Yeah, you got to pick your battles. It’s gotten a fair amount of press. There was a viral video of Michelle Obama, I’m sure you saw this, at a bookstore in Manhattan. And she goes shopping and she pulls out the book and gives it a solid shout out. And then she bought it, which is amazing.

I saw the video because I follow her on social media. I saw the video and she was at a bookstore like, “Oh, it’d be so great if she pulled out our book.” And then she pulls out a children’s book. Then the next thing I was like, “Oh my God.”

View this post on Instagram

So the book is about those first sparks of creativity. What visually reference wise do you draw on? What were your own original sparks of creativity? You mentioned growing up in New Jersey, you were probably an artsy kid.

I was a weird kid, but I’ve embraced it now, but then when people told me I was weird, I was all anxious about it.

Were you bullied?

I was bullied from first grade through twelfth grade, so yes.

But what were those first sparks for you? What do you remember first seeing and being like, “I want to do that,” or “I can do that, that moves me in some way.”

So one of the biggest things was there was this kid named Danny Moskovitz. I was in kindergarten and I think he was in pre-first, the space between first grade and kindergarten for the kids who aren’t ready to move on to first grade. And then we were in first grade together and Danny Moskovitz was just this kid could sit down and draw anything from his imagination and he would tell jokes at the same time and it was just this amazing experience. And I thought, how great would it be to be friends with this kid? And he just gravitated towards me. I gravitated towards him. So just sitting around and watching him make art, it wasn’t the first thing, but it was probably the biggest thing.

It was a friend. It wasn’t like a book that you picked up? What was your first favorite book or even classics that you go back to as touchstones or reference points?

My first favorite book, the ones I remember, I was in second grade, so someone gave me a copy of “The Illustrated Bible” for Christmas, and then there’s the D’Aulaires book of Greek mythology. Those two books were the books that I remember the most. We didn’t have a lot of children’s books in my home growing up. But when we’d go to the doctor’s office, there was always a ton of children’s books and that was one of the high points. Golden Books were really popular back then. It was the early ’70s so the books weren’t necessarily from the ’70s. They were also from the ’60s, just that era, mid-’60s, early ’70s era of children’s book illustration has always been a major inspiration to me.

I remember Highlights magazine at the dentist. You grew up in Jersey, you moved to Brooklyn for college, right? You go to Pratt. And you didn’t necessarily set out to be a children’s book illustrator. Talk about that. How does one drift into and become so prolific and successful in that niche world?

Illustration is a little bizarre world. I think when I got to Pratt, I didn’t know much about art any sort of major way. I think when I was 18, Ultra Violet who was part of Andy Warhol’s inner circle, part of his Factory, had written a memoir about her time with Andy Warhol called “Famous for 15 Minutes,” and that was my first entry into sort of learning about a fine artist. I didn’t know about Picasso or Michelangelo or da Vinci or anything like that. So when I got to Pratt, most of my exposure to art was really commercial art, either book jackets or children’s books or any type of illustrated book like the Bible or mythology books, record covers, advertising. That was really my entry into art, so I thought I wanted to be an illustrator.

Then once I started taking illustration classes, I didn’t feel so connected with the students and I had started learning more about fine art. I sort of toggled between fine art and illustration at Pratt, so I was initially an illustration major and the whole idea of being given an assignment and being sort of locked into an idea annoyed me in school. It’s like a language that you learn how to talk after a while. So I toggled between the two. And then I had a great professor at Pratt, Anthony Cyrus, who was in the fine arts department, but he had been an illustrator. So he really gave me a lot of great feedback on my work and just really sat down and took the time to listen to me, which was really, really meaningful.

But you leave Pratt.

And then when I left Pratt, I started working at the Brooklyn Museum and I still wasn’t sure if I wanted to do fine art or illustration. At that time, Basquiat had died and his work was really blown up and everywhere, and I was really inspired by his work. I think the thing that people get inspired by his work is just really his sense of self-expression. And especially for a young artist, he was so good at expressing himself.

In the mid-’90s I decided to take a couple of illustration classes like continuing ed at [the School of Visual Arts], so I started putting together a portfolio. I wanted to do a bunch of things. I mean, I wanted to do graphic novels, I wanted to do magazines, I wanted to do book jackets and then children’s books, and I thought I could do all of that stuff within a year’s time. I’d be making a graphic novel, a children’s book. In the early 2000s I got focused on doing more sort of magazine work, which was very glamorous at the time. It was very glamorous to be in the New Yorker or something like that. So despite all of my efforts to get published in The New Yorker, they ignored all my promotional material.

I’ve tried and failed a number of times. I came really close once to writing a piece for them, but they killed it. You were doing stuff for like Pulse. For people listening, magazines used to be cool.

Pulse was like a magazine from Tower Records, so anything that was music related was really exciting to me. I started sending out a lot of promotional material and what happened is the children’s book imprints at different publishing houses responded to my work and they would call me in for interviews. And at that time I was, I think maybe in my late 20s, early 30s and I just wanted to be a full-time illustrator and stop working other jobs. I would go in for an interview and it was kind of exciting, but the first two times I didn’t get offered something. I think the third time I went in I was offered a book. Also I did a sample piece for that book and then they gave me a contract. And then the other two interviews I had gone on actually within probably about six months also gave me offers. So I went from doing little bits and pieces of illustration for magazines to having children’s books snowball all of a sudden. And quite honestly, I mean I think that was maybe 2004, 2005. Things haven’t stopped since.

I do like how you’ve managed to combine different aspects of your own personal interests, your personal life, into your professional work, whether it’s music, you were interested in education, Black icons, fatherhood. You’ve done children’s books about John Coltrane, Ella Fitzgerald, Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass, the Love Family. Talk about incorporating aspects of yourself into your work, which you’ve managed to do consistently and very effectively.

Well, thanks. The first book that I was offered that really spoke to me in a major way was the biography of Dizzy Gillespie written by Jonah Winter. So Jonah Winter is an incredible children’s book author. He had previously written a book about Frida Kahlo that was amazing. He decided that he wanted to write the book about Dizzy Gillespie in the voice of a beat poet. And Jonah’s such a great personality and he’s almost like a fearless artist. His parents are both artists, at least his mom is an artist, an illustrator and author. And so he’s got this fearlessness when it comes to creating. And I loved that he was telling this story about Dizzy Gillespie that was very truthful and honest and fearless, but also very heartfelt. As someone who loves music, as someone who loves jazz, and as someone who felt like a weirdo and sort of oddball his entire life, I resonated with the story.

And then from there, I got sort of known as the jazz guy, so I got a lot of jazz books. But then I also felt like I wasn’t expressing enough of myself through my art and I started looking for subject matters that I wanted to use in creating my own fine art that was separate from my illustration work. So I started digging back into my childhood and some of the things that I had heard about but didn’t really quite understand and I wanted to use my art in my past as this way of exploring different ideas.

I thought about the children’s book Little Black Sambo and how that Sambo was this taboo term and how that was a banned book at the time, and I read it just to get a better understanding of it. And I looked at it and wanted to sort of extract some of the interesting ideas I thought from the book and then reinvent this character. So that’s really was the emphasis of me building more of a body of work that was really about me and about my history. And then from there, I’ve just gone on to other subject matters.

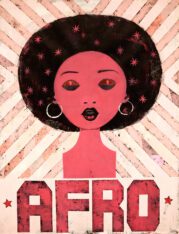

The Young Magician (Illustration by Sean Qualls)

The Black Sambo character that you were talking about, is that the boy magician that pops up in your work?

Yeah, I’ve renamed him. It was initially Sambo. I called him Sambo. And I was like, I don’t want to be the guy who’s just trying to go for the provocative language, so it just renamed him The Young Magician.

He pops up in your fine art. What does he represent to you? He’s a little magician, a little boy in a top hat. Your work does have a magical aspect to it. What is this magician character?

One of the things I extracted from the story that really resonated with me that then has become a theme in all of my fine art and even in the books that I do, is he was a self-defined person. Me recreating him was a further attempt to give him this self-definition. So forget the labels that have been thrown on him historically, this was going to be a very self-defined character. And in the book he has these sort of magical qualities in that he’s basically sort of being attacked by tigers and he finds a way to outwit them. That’s the big takeaway from that story for me. So in recreating him, he was this mythical and self-defined character.

It then snowballed for me and I started thinking about Black exploitation movies, Melvin Van Peebles and Sweetback, and how Sweetback was this mythical self-defined character and how I think in art in general and where art and literature and music all sort of meet, I love Sun Ra, the jazz musician and all these people, they have mythical qualities, these self-defined mythical figures. That’s really what cemented the idea that I wanted him to be the forefront of my work. And so he sort of comes in and out. I also paint other things.

People who are curious, they can see your fine art now at the Established Gallery, the very northern tip of Park Slope. You have a show there now called “Inner Victories.” What do you want people to take away from that? What is show?

Well, the title is just based on the idea that personal victories precede public victories. As an artist getting into the studio and making your art, it’s the essential quality behind everything. It’s what we do in private. We have to put in the time in our private lives in order to sort of have the personal rewards that we’re looking for. Anyone we really think of, from Beyoncé to whoever, it’s all the unseen hours that one puts in eventually comes out.

The 10,000 hours.

Yes, absolutely.

Talk about the fine art versus children’s book illustration. Do you worry ever about being pigeonholed as just a children’s book illustrator? Are you proud enough as being a children’s book illustrator so you don’t care? Is there a tension at all there, you want to be taken more as a fine artist or they’re both coexisting?

For a while I was worried about being labeled as “just” a illustrator or just a children’s book illustrator, but it’s such a privilege to be able to make your art on a daily basis and make a living from it, so I see myself as an artist and illustrator and soon-to-be published author.

Talk about that. You have books coming up.

Yes, four. The first of them is a middle grade nonfiction book about the history of Black hair in America. It’s my personal love letter to Black hair. “Black” meaning African-American hair and all the amazing things it does and the history of it. It has these nods in children’s books literature where people wrote books about taking care of their child’s hair. But just in terms of the history, I think there’s a big missing piece. That’s going to be the first book in the series.

It’s middle grade, which is a little different for me. I usually do picture books, but I’ve done a few middle grade books, so I hope it appeals to not only middle grade readers, but people of all ages because it’s such a big topic. A couple of the other books are music focused. One is sort of a history of Black music in America, but it’s not really a literal history. It’s about how music is part of Black culture and throughout our history in the States, it’s been something that we’ve used to get through the difficult times and to make the good times even better.

Illustration by Sean Qualls

I like that. I did want to bring up the role that race plays in your work because it is a very central motif, theme. You lean into aspects of the culture, but it’s through a lens of joy and curiosity and obvious pride. What do you hope to express or what do you hope to address?

Friends of mine had a teacher at SVA named Marshall Erisman. He was an illustrator, but he was also a fine artist and he was such a joyful person if you ever met him in person, but he had the darkest artwork. His artwork was so frightening. He used to have this quote, I forget who it was from, but it was something like, “eat like the bourgeois, sleep like the bourgeois and save your anger for your art.” The initial impetus for me was I wanted to create art that had Black people front and center as the main subjects because I wasn’t seeing that in the television or films or literature that I was reading. And if I did, it was a very particular take on Black identity. It wasn’t expansive. It was just sitting in the same realm. I think that was really my initial impulse to create art that had Black people at front and center to be a focal point of the work and their stories.

I think more recently, within the past four or five years, Black people are still front and center in my work, but the idea sort of expanded, which is really just I want to make work that elevates humanity. The important part of having Black people in it at this point, it’s an aspect of humanity and culture that’s not really given the weight that it should and this sort of expansion and identity of Black people, from my perspective, something that really needs to happen. Further along that path, it’s addressing the idea that, as human beings, not only Black people but human beings in general, we can define who we are ourselves and that we’re not defined by outside sources. I think that’s one of the greatest human struggles, quite honestly, and I think it’s our greatest power as human beings is to be ourselves and to define ourselves. That’s really what it’s become about. Black people are part of that right now, but it’s really about being human more than anything.

And that goes back to what you’re doing in your show at the Established Gallery, and so it’s clearly a through line. It’s funny though because you talk about being yourself and self-actualization and all that. But if you think of yourself as one way, but everyone else in the world sees you in a completely different way, which way are you really? Who does get to define that?

It is a bit of a mind trick or something like that. But I think so many people who have made meaningful contributions to our world weren’t seen as the person they wanted to be seen by the outside world. The first person that comes to mind is Andy Warhol. Andy Warhol was an illustrator at one point and he wanted to be an artist, so he started making art that was very influenced by his illustration or by commercial art, and it was at the very beginning of pop art. Yet Andy Warhol wasn’t accepted by the other pop artists. Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns didn’t like him. They were both gay, but they thought he was too gay and they didn’t like his work. It’s like, “Fuck them,” to an extent. Andy Warhol, when you talk about pop art, he’s the king of pop art. Everyone knows who he is. Not everyone knows who Jasper Johns or Robert Rauschenberg is, even though I love their work. There is that time where you have an inner conflict.

You pride yourself on working by hand. There’s no digital manipulation or touch-ups of any kind. What is your medium? It’s collage work, it’s painting, drawing. What is your main medium?

Drawing and painting really. I paint on paper a lot in a lot of my collage material or if not all of my collage material, but most of it is painted papers that I create and then just put aside until I want to use them later, so they’re created with different colors and textures that I then incorporate into my work. So more than anything, I’m a painter and the collage aspects are really just work that I’ve also created, so it’s not like using magazine materials collage. Even though I do that here and there, it’s not the dominant part. It’s a very sort of minor part of what I do.

Talk about creating art for an adult versus creating art for a child. Do you draw a distinction between the two? A lot of your so-called “fine art” or a grownup art, whatever, has a childlike quality to it and vice versa. You don’t shy away from big ideas in your children’s work either. So is there a distinction?

The one major distinction for me is, in working as an illustrator, there’s a certain level of editing that I have to do that I don’t do in my fine art. Even though I’m sort of bringing my experience from childhood and things that I wish I had seen or things that excited me, things that I did see and things that excite me as an adult, I am not necessarily editing myself in my fine artwork. Obviously in fine art I get to decide the parameters and so I can make things as big as I want.

In terms of illustration, there’s a trim size, so what is the final product going to be trimmed to? A page in a children’s book or a magazine cover or book jacket. You’re meeting with other people like an editor, an art director, and there’s discussions about what the audience is going to think about this and that and the other. I do love them both. Each of them make the other aspects stronger. So working as an illustrator, I can edit myself as a fine artist because I’ve learned how to do that to make a stronger image for my fine artwork. And as an illustrator I can bring some of the elements from my fine art, that I’m more free in, to I do there.

You have two kids. Our kids are the same age, yours and mine. They basically grew up on your books, right? Or did they shrug it off? Oh, that’s just Dad’s doodles. Or did they connect the two?

They grew up a lot with my books and their mother’s books, who’s also an illustrator.

Selena Alko, let’s shout her out.

They both grew up with art and creativity being a backbone of their childhood. My daughter goes to Art and Design High School, but she says she doesn’t want to be an artist. She’s interested in pursuing law. And my son is very much an artist and he’s working on an illustrated book of some of his poetry.

You didn’t try to talk him out of it? “Go to law school and do art on the side. Make money first.”

I’m happy my daughter wants to be a lawyer. Lawyers buy so much art, so hopefully her friends will buy my work. She’s very good at, verbally, all the stuff that lawyers do. And then my son, he’s great. I think we can be successful in any field that we’re in. It’s just a matter of the 10,000 hour idea. You’re putting your time and hopefully you’ll float to the top.

You stick around long enough, you’re good at what you do. Typical day in Park Slope, you are in the south end of Park Slope or call it Windsor Terrace, call it whatever you want. What’s a typical day for you? It doesn’t have to be in Park Slope. You don’t have to make art. Where do you go? Where do you hang out? What do you do?

If I don’t have to make art? First of all, I go crazy if I don’t make art every day, so a typical day I’m going to mix it with an ideal day. I wake up, I do some exercises, I do some journaling. I swing into making some art, especially on the early end. Go record shopping at Psychic Records, which I love. Have a little artist time at Couleur Cafe, which I also love. I mean there’s so many great places for dinner. Maybe meet a friend like you at Double Windsor for a drink for lunch. Dinner, I really like Lore. I’m mostly vegan. I eat fish also. Their menu has really changed, accommodates me more now, which is great, and their cocktails are pretty amazing. I walk through Windsor Terrace early in the morning, which is a very quiet walk, and evokes growing up in a small town for me.

Check out this episode of “Brooklyn Magazine: The Podcast” for more. Subscribe and listen wherever you get your podcasts.

You might also like