Politics and DIY at the Indie Memphis Film Festival

There was something befitting in spending the final days in the run-up to one of the most divisive presidential elections in US history down south in Memphis, Tennessee. A deep blue city in the far corner of an all-red state, Memphis is a place that’s united by an easygoing vibe, even as it remains divided and largely segregated. For a New Yorker and first-time visitor, however, it offered escape from the pre-election noise and anxiety. Home to Aretha Franklin, Booker T, and Otis Redding, it’s a music town first and foremost, with a soundtrack for any age, but especially ours it seems, when words alone feel powerless against the sad and outlandish spectacle of our political moment. As it happened, I wasn’t in town for music, but for movies. The 19th Indie Memphis Film Festival, a weeklong showcase of 185 films that combines an eclectic mix of local fare and savvy selections from Cannes, Sundance, and other festivals, wrapped up the day before the election. Anchored this year by an exciting line-up programmed by Brooklyn-based writer and filmmaker Brandon Harris (a sometime contributor to these august pages), the festival, infused with the city’s warmth and buoyed by the local music acts (they play before each screening), ranks as one of the more satisfying regional film festivals around. Where else do you overhear folks debating BBQ and fried chicken houses while in line for the latest films by Kelly Reichardt and Raoul Peck?

There was something befitting in spending the final days in the run-up to one of the most divisive presidential elections in US history down south in Memphis, Tennessee. A deep blue city in the far corner of an all-red state, Memphis is a place that’s united by an easygoing vibe, even as it remains divided and largely segregated. For a New Yorker and first-time visitor, however, it offered escape from the pre-election noise and anxiety. Home to Aretha Franklin, Booker T, and Otis Redding, it’s a music town first and foremost, with a soundtrack for any age, but especially ours it seems, when words alone feel powerless against the sad and outlandish spectacle of our political moment. As it happened, I wasn’t in town for music, but for movies. The 19th Indie Memphis Film Festival, a weeklong showcase of 185 films that combines an eclectic mix of local fare and savvy selections from Cannes, Sundance, and other festivals, wrapped up the day before the election. Anchored this year by an exciting line-up programmed by Brooklyn-based writer and filmmaker Brandon Harris (a sometime contributor to these august pages), the festival, infused with the city’s warmth and buoyed by the local music acts (they play before each screening), ranks as one of the more satisfying regional film festivals around. Where else do you overhear folks debating BBQ and fried chicken houses while in line for the latest films by Kelly Reichardt and Raoul Peck?

With a few hours to kill before my first screening, I wandered from my swanky hotel in gentrified downtown Memphis and quickly stumbled on historic Beale Street, the city’s famous strip of blues and rock clubs, where music—both live and recorded—spills out onto the street at every hour, and people—mostly tourists—jostle for a taste of the real thing. Memphis, as I discovered, is city of ghosts. You don’t come here to escape history. At every turn, you’re reminded that its rich cultural heritage is entwined with the deepest political struggles and economic hardships this country has endured. Traces are everywhere, as are some misguided attempts to pay tribute to a lost Memphis. The city’s downtown, once a bustling center, fell into decline decades ago, and generic revitalization has erased parts of its distinct flavor. Now, instead of trolleys on Main Street, buses dressed up like Disney-fied versions of antique trolley cars ride over top of the old rails still embedded in the street, shuttling visitors to and fro while homeless people look on.

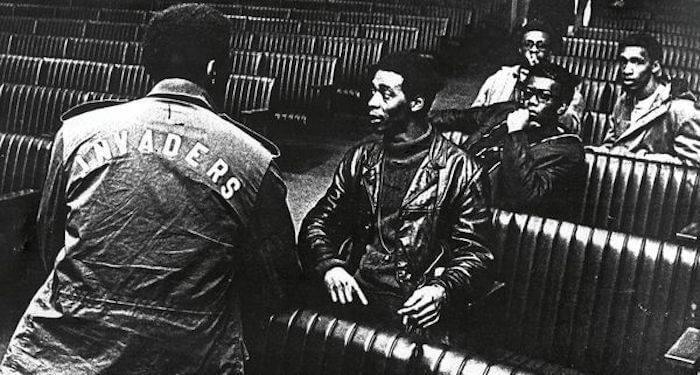

But there are also vital and inspiring examples. The Lorraine Motel is here. The site of Dr. Martin Luther King’s murder in April of 1968 is today the National Civil Rights Museum. The original structure has been merged into the museum. At the end of an exhaustive exhibition that begins with the slave trade and details every step in the Civil Rights movement, you can peer into Room 306, where Dr. King spent his final hours, and glance out at the balcony where he stood and fell, that image immortalized of his body, flanked by associates pointing in the air toward the gunshot, now part of our collective memory. It’s a chilling and unforgettable experience—required viewing for white America especially. And I’m ashamed to say that until I watched Prichard Smith’s fine documentary The Invaders, which opened Indie Memphis this year, I had largely forgotten the story of what brought Dr. King to Memphis that spring. Smith’s film is a portrait of the eponymous Black Power activist group formed in the city in 1967 to organize citizens against slum landlords and police brutality. Its members were among the few to visit and speak with King at the Lorraine hours before his death. They were there to negotiate with him, after a non-violent protest they helped organize turned violent. The Invaders had helped organize a strike of the city’s African-American sanitation workers that caught national attention and inspired King to join, along with his Poor People’s Campaign. The film’s style can feel over-determined (Smith has worked for Vice), but it features extensive archival footage and interviews with remaining members, and stands as an important document of an overlooked moment in Civil Rights history, made all the more relevant after the country’s predictably egregious display of historical amnesia last week.

Making the film was a hometown effort for Brooklyn-based Smith and producer Craig Brewer (Hustle and Flow), both native Memphians. Many of the original Invaders claimed the stage in a rousing Q&A that followed the screening. Similar enthusiasm greeted Jake Mahaffy’s feature debut Free in Deed, receiving its hometown premiere after winning the Horizons Section at Venice. Shot on-location in Memphis and featuring many local non-professionals, Mahaffy’s gritty and intense drama was a standout. Set in the little-seen world of Memphis’s largely African-American storefront churches, it follows Pentecostal minister Abe (David Harewood) who decides to help Melva (Edwina Dickerson), a struggling single mother, by curing her son’s (Rajay Chandler) severe autism. The performances are all terrific, especially Chandler, whose utterly realistic portrayal convinced me he wasn’t acting at all. While Mahaffy misses the opportunity to develop Abe and Melva’s relationship, the movie is tough and arty—not a crowd-pleaser, really, even if it was treated it as one. Still, faith is a theme rarely tacked with such tenacity, and Free in Deed takes seriously the salvation offered by impassioned faith, as well as its unintended consequences. Its aided by the expressionistic cinematography and droning sound design, which push the film beyond realism, transforming the cramped, fluorescent-lit faith houses into dramatic stages for booming voices and spiritual healing.

In Memphis, magic is often hidden behind nondescript storefronts. Ernestine & Hazel’s occupies the other end of the spiritual spectrum as the city’s iconic brothel-turned-haunted bar that serves up beer and Soul Burgers. (They don’t ask you how you want it, which is great.) The festival organized a get-together there because it’s one of the few remaining places that give you a taste of pre-gentrified, down-and-out Memphis—an atmosphere that captured Jim Jarmusch’s imagination in his Memphis-set 1988 film Mystery Train. In the mid-90s, parts of downtown were still unchanged from the 1970s, which is why Milos Forman used the city as a stand-in for 70s-era Cincinnati in his biopic The People vs. Larry Flynt. There was a special 20th anniversary screening of the film (the only one to screen on 35mm), which has lost none of its irreverent energy, as a tribute to Emmy-winning screenwriter Larry Karaszewski (The People vs. O.J. Simpson), who was serving this year on the Narrative jury. Made the same year, Ira Sach’s debut The Delta was also receiving a special anniversary screening. Before Sachs became a chronicler of modern New York, the Memphis-born director turned his camera on his hometown for this tragic romance between a middle-class white kid and a Vietnamese immigrant. A classic of New Queer Cinema, it remains one of the director’s best.

Despite being part of cinema history, however, Memphis has long struggled to compete with Austin or Brooklyn as a production hub. According to Ryan Watt, director of Indie Memphis, this is largely due to the lack of all-important tax incentives offered by the state, instrumental in attracting small and big budget productions. Filmmakers shooting in the south instead favor neighboring Louisiana and Georgia. And while this has hurt Memphis’s film industry in the last decade and a half, it has also spurred a scrappy, tight-knit community of DIY filmmakers who make movies because they want to, and not necessarily as a full-time career. Most are locals who want to stay local. In an effort of support, Indie Memphis devotes a third of its slate to films made in the city and neighboring five counties, and hands out more than $20,000 in monetary and in-kind grants.

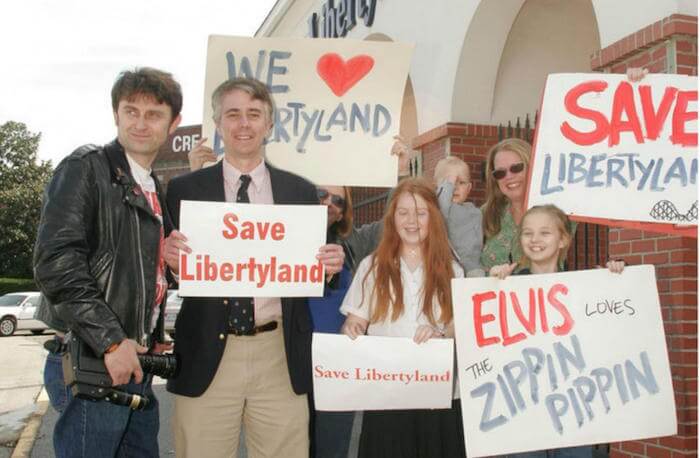

Among the more singular entries in the Hometowner section was artist Madsen Minax’s Kairos Dirt & The Errant Vacuum, an experimental narrative about a diverse group of Tennesseans connected by mystical forces that gleefully elides genre and gender categories and took home the Best Feature prize. A more obvious example of Memphis’s DIY ethos is apparent in Mike McCarthy’s rough-hewn documentary Destroy Memphis. Starting in 2005 and shot on a camcorder, this home movie tracks a grassroots crusade by an all-girl punk band and a DC lawyer to save the Zippin Pippin, Elvis’s favorite roller coaster, that was slated for demolition to make way for generic development in Midtown Memphis. The Zippin Pippin also inspired the band’s name, and the film’s offbeat humor derives as much from the sibling rivalry undermining every performance, as from the absurd minutia of municipal politics that embroils the group. As the years click by, the coaster crusade, emboldened at each set back, seems fruitless— and turns Destroy Memphis into a batty meditation on nostalgia and our impulse to preserve things at any cost. But if the fate of Elvis’s rollercoaster felt inevitable, the displacement of Brooklyn underground music venue Death By Audio by the hipster media empire Vice felt more than a little ironic. Matt Conboy’s Goodnight Brooklyn, playing in the Documentary section and covering roughly the exact same time period as McCarthy’s film, tracks the rise and fall of the beloved “anarchist temple for community” he helped found, paying tribute to its DIY ethos while indicting the ruthless corporate tactics of a company that owes its existence to the very places it has helped eliminate.

Raoul Peck’s powerful James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro offered an urgent reminder of how little racial politics have changed in this country since the 1960s. Back on gentrified Beale Street, I passed by a gallery devoted to Civil Rights photographer Ernest Withers, whose images helped make iconic the “I Am a Man” signs we see carried by protesters in The Invaders. Decades later, the sign inspired the work of African-American conceptual artist Glen Ligon, whose 1992 painting “Black Like Me No. 2”, with its black text stenciled on a vertical white field, was among the first pieces selected to hang in the White House by the newly elected President Obama in 2009. I couldn’t help but wonder what crass emblem of corporate power would replace it now, and what, if anything, art can really do at this moment.

You might also like