Sully and Clint Eastwood’s Right-Wing Myth-Making

For all the attention and criticism generated by Clint Eastwood’s recent comments in Esquire—“We’re really in a pussy generation. Everybody’s walking on eggshells. We see people accusing people of being racist and all kinds of stuff. When I grew up, those things weren’t called racist.”—little notice was given to the fact that in that interview Eastwood barely discussed his own movies. Furthermore, two films he did discuss allowed Eastwood to circle back to politics. First, without a shred of facetiousness Eastwood suggested that pilot-hero Chesley Sullenberger, the protagonist of his latest film, Sully, should run for President of the United States. Second, the director explained that Gran Torino was a response to that classic bugaboo of the right, political correctness.

For all the attention and criticism generated by Clint Eastwood’s recent comments in Esquire—“We’re really in a pussy generation. Everybody’s walking on eggshells. We see people accusing people of being racist and all kinds of stuff. When I grew up, those things weren’t called racist.”—little notice was given to the fact that in that interview Eastwood barely discussed his own movies. Furthermore, two films he did discuss allowed Eastwood to circle back to politics. First, without a shred of facetiousness Eastwood suggested that pilot-hero Chesley Sullenberger, the protagonist of his latest film, Sully, should run for President of the United States. Second, the director explained that Gran Torino was a response to that classic bugaboo of the right, political correctness.

In a strange and circuitous way, Gran Torino seems to have borne Sully as a politically motivated project. As we all know, on January 15, 2009 Sullenberger executed an emergency landing of US Airways Flight 1549 on the Hudson River, saving the lives of over 150 people. On that day Gran Torino had been in theaters for just a little over a month, on its way to becoming, at the time, the most financially successful—and most discussed—Clint Eastwood-directed film since 1992’s Unforgiven. (Sully provides a very brief glimpse of Eastwood on a Gran Torino billboard as Sullenberger jogs through Times Square.) Torino also marked the last time Eastwood starred in one of his own movies; given that Hollywood’s “Last Classicist” (as designated by Dave Kehr, among others) is now 86 years old, it’s not far-fetched to assume it will remain the last.

In Eastwood’s most effective films the hero is often played by Eastwood himself, riffing on The Man With No Name and Dirty Harry roles that made him a screen icon. Not coincidentally, after Torino Eastwood struggled to tell the story of a protagonist (Nelson Mandela, J. Edgar Hoover, Frankie Valli, a psychic played by Matt Damon) who didn’t evoke the director’s own laconic lone gunman persona. Finally, in American Sniper (2014) Chris Kyle became the most Eastwood-like hero since Eastwood himself; again not coincidentally, the film became Eastwood’s newest largest grossing effort. Sully, which opens in theaters tomorrow, likely won’t repeat the enormous box office success and cultural controversy of Sniper, but it may very well continue the restoration of the Eastwoodesque hero. If so, no one should be surprised—while Sullenberger isn’t a lightning rod like Kyle, he nonetheless exists in the political arena, at least if Eastwood has anything to say about it. Heck, in Clint’s world he’s commander-in-chief.

Diverse in subject matter, Eastwood’s directed films typically tinker with a single political shibboleth. Putting aside a few uncharacteristic outings (which also comprise some of his best work, such as the soft-focused May-December romance Breezy), Eastwood’s movies continually expound upon anti-authoritarianism’s basis in violent masculinity: High Plains Drifter (1973), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), Sudden Impact (1983), and Unforgiven, among others, center on protagonists operating outside the law, dispensing bloody justice in an American landscape that’s only cosmetically civilized. A registered Libertarian, Eastwood has explored to varying degrees of complexity this quintessentially conservative theme, in which the steely individual must combat—sometimes from within (The Rookie, 1990), sometimes from outside (Pale Rider, 1985)—official systems of governance that inherently court corruption in an inherently inhospitable universe. (Not for nothing is one of Eastwood’s sillier thrillers—in which an honorable thief witnesses a U.S. President’s involvement in the killing of a young woman—titled Absolute Power [1997].)

By exposing the political and moral vacuity of this myth, Unforgiven has been deservedly recognized as Eastwood’s masterpiece. In this Last Great Western, notorious cold-blooded killer Will Munny (Eastwood) wages war against a crooked sheriff and his posse out of mercenary opportunism and personal revenge as much as newly discovered ethical convictions. The redemption Munny earns by working for a group of victimized prostitutes is offset by his indiscriminate and unshakeable lust for destruction. “Any man I see out there, I’m gonna kill him,” he yells at the film’s disturbing conclusion. “Any son of a bitch takes a shot at me, I’m not only gonna kill him, but I’m gonna kill his wife, all his friends, burn his damn house down.” Here the “legitimate” motivations behind the maverick’s brutalism are called into question just as emphatically as those of the authority-abusing villain. Understandably, in sundry subsequent films Eastwood has revisited through contemporary tales of extra-legal vengeance (the overwrought Mystic River [2003]) and lionized militarism (the understated Flags of Our Fathers [2006]) Unforgiven’s demythologization of the relationship between rugged American masculinity and “justified” violence.

Other Eastwood work in this vein, however, is less than morally or intellectually honest. Based on a novel by KKK leader and George Wallace speechwriter Forrest Carter, Josey Wales promotes the historical falsehood that only Union soldiers committed atrocities during the Civil War, and that Confederates were only defending their independence against government repression. Even when Eastwood helms ostensible can’t-miss Oscar bait—and since Unforgiven he’s done this far more frequently than his unpretentious rep would suggest—he sidesteps investigations of social systems and their ideological foundations to paint simplistic portraits of individual resilience (in Changeling [2008] Angelina Jolie’s Depression-era heroine battles power-abusing law enforcement and mental health institutions in attempting to find her kidnapped son) and failure (in J. Edgar [2011] Leonardo DiCaprio’s Hoover embodies federal overreach).

Which brings us back to Sully. This is a film that by all appearances has little reason to exist: perhaps there’s an audience for the recreation of one of the greatest miracles in commercial aviation, but how many people will care about the trials of Sullenberger, whose courage and flying talent are worth at most half an hour of screen time (twenty minutes more than the entire ordeal of Flight 1549)? If that sounds callous, I’ll rephrase the issue: beyond the emergency landing, where’s the conflict in a story of an unquestionable hero with no metaphorical shadow?

Yet this is where Sully illuminates Eastwood’s core politics (as opposed to his issue-by-issue beliefs, which often fall on the left side of the political spectrum: pro-gun control, pro-choice, pro-gay marriage). The film places less dramatic emphasis on Sullenberger’s split-second actions or the doubts he may have had in committing to them than it does on the Monday morning quarterbacking he suffered when investigated by the National Transportation Safety Board. True, this angle unto Sullenberger’s heroism continues Eastwood’s penchant for stories of wounded or besieged masculinity, and Sully repeatedly depicts Sully experiencing PTSD as well as discomfort with instant fame. Yet humanizing the (always reluctant) hero has often allowed Eastwood to buttress his strong individualism v. soft collectivism narratives. In Sully the hero fends off charges of recklessness—the NTSB contends that he could and should have navigated 1549 back to Laguardia Airport—by demonstrating that the investigation into the landing, especially with its reliance of flight simulators, has taken “all of the humanity out of the cockpit.” Sully embodies such humanity in his courage and humility, but despite the overwhelming adoration he receives—even the NTSB bullies come around at the end—he remains a solitary figure, bound to duty yet isolated within a number-crunching institution that looks down on old-fashioned self-reliance.

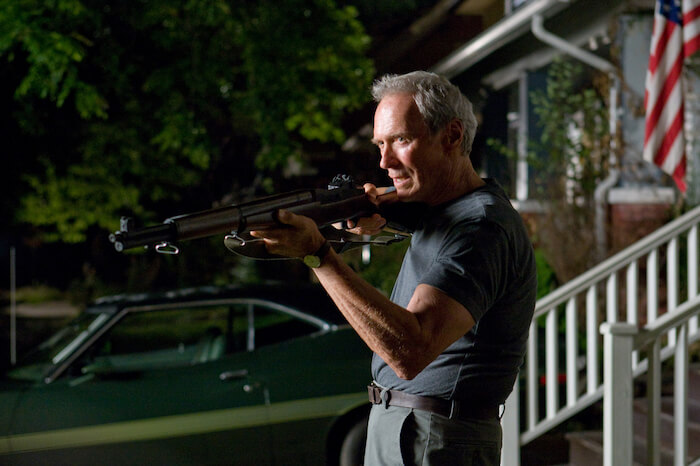

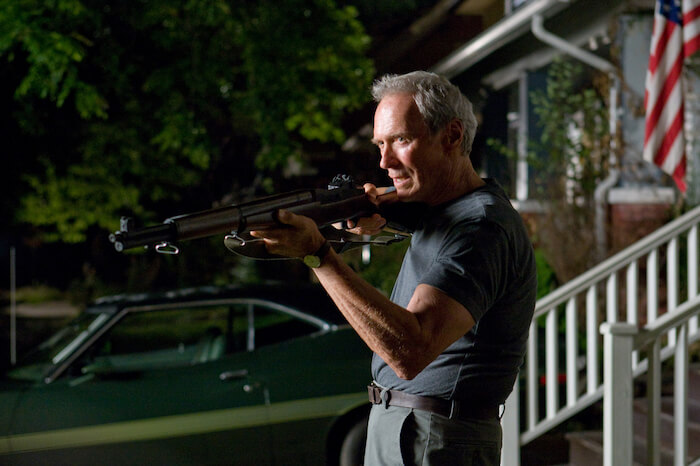

A similar dynamic occurs in Torino, a cynically calculated film in which Dirty Harry playacts a critique of his screen legend while actually retooling it for contemporary audiences. Torino expresses the current canard that unabashed bigotry can act as some sort of sanctified weapon against the horrors of PC culture. The redemption of Eastwood’s Walter Kowalski doesn’t involve his realization that racial slurs are demeaning and indicative of a malformed worldview—the character goes right on spewing bile even after he befriends his Asian neighbors. Instead, the film conflates the character’s racism—or the very least his race-baiting—with “old-school,” no-nonsense, but ultimately “human” machismo in contrast to the modern, materialistic, hypocritically polite world around him. Plenty of arguments can be made against the legitimate problems of political correctness as it pertains to the censorship of ideas and the euphemistic avoidance of healthy, contentious debate. But Torino isn’t about that—it’s all about about pandering, about throwing in with the Alex Jones (and now the Donald Trump) crowd, for whom derogatory insults are an inherent sign of “authenticity.”

Eastwood also disguises conservatism as humanism in Sniper, a film that masks its imperialist outlook behind a “sensitive” depiction of Kyle. Sniper benefits by being Eastwood’s most technically sound film since Letters from Iwo Jima (2006) as well as by avoiding the cartoonishness of Eastwood’s Heartbreak Ridge (1986), a Porky’s version of the invasion of Grenada that could have only been made during the last delusional hours of Reagan’s “Morning in America.” But Sniper’s still a weasily piece of propaganda, sublimating the issues it obliquely raises concerning the pathology of militarism and the senselessness (never the criminality—that would be going too far) of the Iraq War into one more “noble warrior” tale. As depicted in the film, Kyle’s dependence on the battlefield to sustain his masculine identity demonstrates that, at worst, some patriots care just a little too much for their brothers-in-arms. God-country-family: after neglecting family for several years Kyle defeats his insurgent rival and returns home to restore domestic balance. Everything else—including the politics of the war and the fate of Iraqi society—remains in the distant background, out of focus. The most the film reveals about warfare is that “the system” knows less about fighting the enemy than does the individual, intuitive soldier, again restating the core Eastwoodian theme. In the end American Sniper dulls the sharper edges of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker [2008], which foregrounds the pathology of military adventurism by refusing to qualify the protagonist’s heroism as “reluctant.” The Hurt Locker—a film I wrongly admired, with reservations, at the time of its release—sees the Iraq War as thrilling work that could enliven the sociopathic. (If that description makes it appear as if Locker fails to provide a ringing endorsement of militarism, consider that most of Bigelow’s filmography takes sociopathic behavior as an innate quality of the risk-courting danger-seeker she enthusiastically champions.) In contrast, American Sniper provides a tepid endorsement, defending the war as grunt work—Eastwood’s hero is once more duty-bound—that could damage the empathetic. Both films take the political justifications for the disastrous war entirely for granted.

American Sniper was complicit in the Hollywoodization of Kyle’s “legend”; Sully portrays its subject as an everyman-turned-hero second-guessed by a lily-livered bureaucracy. This may make the latter film controversial in a manner similar to American Sniper, though likely not nearly to the same intense degree. Whatever its reception, Sully demonstrates that Eastwood’s “last classicist” approach to filmmaking is often a vehicle for political myth, a myth that has been less interrogated of late than emblazoned. The largest lesson imparted by Sully might not be about heroism or institutionalism but instead about the cinematic imagination of its director, in whose hands even the most politically neutral story can occasion a thoroughly conservative vision.

You might also like