Give Us This Day Our Daily Bread: Talking to Bien Cuit’s Zachary Golper about the Vital Importance of Bread

all photos by Jane Bruce

To hear chef Zachary Golper, owner of bakery Bien Cuit and author of forthcoming cookbook Bien Cuit: The Art of Bread, talk about whole grains, fermentation, and the cultural importance of cultivating grains is to instantly understand why bread plays a vital part in so many religious rituals; this simultaneously humble yet exalted food seems to inspire the purest type of fanaticism.

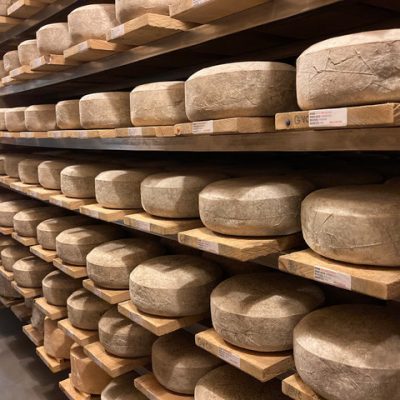

But first: We were interested in talking with Golper because the bread and pastries available at his bakery Bien Cuit have inspired a cult-like devotion in us and just about everyone we know who’s tried them. From the dark-crusted, 68-hour fermented miche to the milky-sweet pain de mie to the inventive éclairs and the tangy, Platonic ideal of a sourdough, everything at the artisanal bakery is exemplary and the technique used to produce each item is more in keeping with the centuries- (or even millennia-) old tradition of baking bread than anything you’re likely to see in most modern bakeries. This is the kind of bread civilizations were founded on, a kind of culinary building block that allowed humanity to stay rooted in one place; it is the opposite of a fly-by-night food trend. We spoke with Golper about his passion for bread, the science behind fermentation, which bakers are the grumpiest, and what makes Bien Cuit different from other bakeries; here is what he had to say.

“I find that there’s a couple of types of bakers. There’s the wholesome, crunchy, back-to-the-earth bakers who believe in milling their own flour and making loaves of bread out of whole wheat and feeding people in a sustainable way. And that’s kind of the motherly type of baker; those guys are usually really easygoing and are maybe a little bit grumpy because they don’t sleep enough, but are otherwise pretty happy guys. You find them out in rural areas, the countryside of Vermont or New Hampshire or something like that. And then you’ve got the more standard baker who doesn’t care a lot about what they’re doing; it’s just kind of what they do. And they use a lot of white flour and they rely on machines a lot, and that’s mostly what the United States thinks of as bakers. They just pump stuff out in massive quantities and most American bakers work at places like that.”

“And then there’s this other group that’s trying to push the envelope. And they’re the most openly hostile ones. Or at least the grumpiest, because they’re fighting an uphill battle to try and change the way sourdough is made, to really try and make as good a product as possible. And there are definitely several of those bakers in New York, and several throughout the East Coast, in general. Those bakers do not make up the mass of the population. And maybe they’re not really hostile, but it’s because being competitive in nature is something that requires a bit of an edge, but I think it’s just because they care and they’re trying to achieve something they are passionate about.”

“I have such a great team now, that it’s possible to say to them: Let’s definitely do something out of the box. If we decide to do something that’s completely different, it’s going to involve a lot more work, but they’re still excited to do it. And that’s rare. That’s actually probably one of the things that sets us apart. People aren’t just there for the paycheck. They’re paid, and they’re paid very fairly, but they’re also fascinated by what they’re doing—the slow fermentation and the grain blending. I don’t even have to go to the warehouse very often anymore because they’re so good at their jobs. The whole thing where at the beginning I was working 20 hours a day—it’s over. It’s not that I totally relax now, but I know my team is doing an amazing job. The most beautiful thing is the consistency that I see now. That is a sign of success, much more so than how much I’m sleeping. What we’re trying to do is support the right kind of farmers and millers, and guarantee that as we’re feeding thousands of people every single day, we’re doing it with a beautiful sense of integrity.”

“Probably 60 percent of baking bread is just understanding it on a biological level. In the Robert Heinlein book Stranger in a Strange Land, he talks about something called ‘grokking,’ which is where you get something, you understand it. And it happens with baking too—you understand what the yeast and bacteria want. And then there’s the other 40 percent, which is science. You get into what’s going to happen, what’s going on in that little tiny ecosystem and what are you going to have to do to get the results that you want. It’s a lot like parenting. You go with your gut, but at the same time there are some simple facts you have to pay attention to; there’s some science involved.”

“Over the course of my career I’ve had some really interesting opportunities to do some experimenting, to try different flours, to try different ways of fermenting things. It’s in this way that I’ve really found out how I’m going to get the most out of certain grains. And so it’s like knowing this is having an extra tool in my tool box.”

“Most bakers are really proud of their sourdough. If they’re not proud of their sourdough, there’s something wrong. It’s temperamental. It’s like a baby. It wants to be fed this way one day and this way another. That’s why it’s really impossible to completely mechanize artisanal baking. It’s not actually doable, unless you twist that word ‘artisanal’ around. Once you start adding things instead of just allowing for the slow fermentation, you’re abandoning different flavors and different aromas. The key ingredient is time—time and temperature. And paying attention to this is what sets us apart from most bakers here, but not in Europe.”

“This kind of bread baking is not new to Western Europe or Northern Europe. There’s still ovens there that are five hundred years old that are still used. These people haven’t stopped what they’ve always been doing. There’s a Basque phrase: In order to push our culture forward we must go backwards. And I think that’s the same thing when it comes to bread-making. We’ve got to look at what worked; we have to look at how it was done for thousands of years. It was grain that allowed us to stay in one place, and eventually develop civilization. If you break it down, it’s essentially bread and beer that did it. (Brooklyn Magazine: That’s not a bad way to start a civilization!) Or maybe it’s the root of all our problems?”

[metaslider id=36577]

You might also like