“Fiction Is Just Another System of Navigation”: Talking with Margaret Eby about South Toward Home

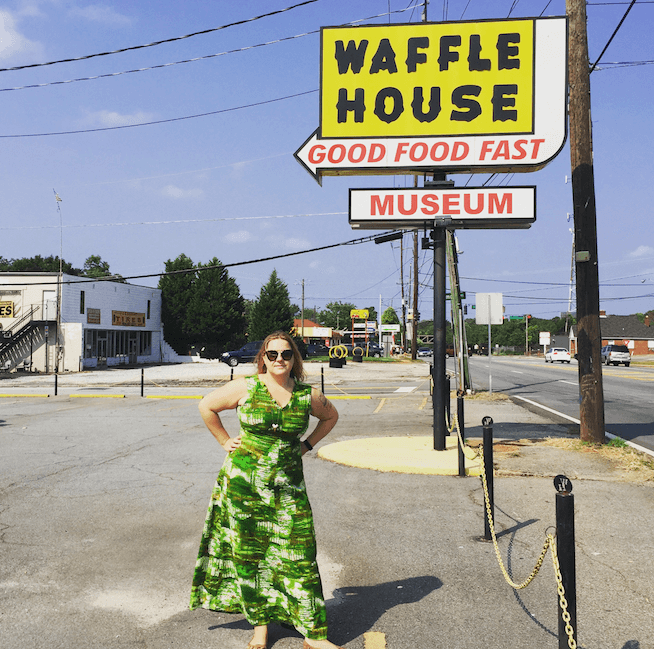

The ultimate Southern destination: Waffle House

“You couldn’t have made up this mule farmer,” writer Margaret Eby says over drinks at King Tai, a Crown Heights bar that serves piña coladas on the rocks. She’s talking about the cousin of Harry Crews, the cult-favorite Georgia novelist whose 1978 memoir, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place, Eby had set out to trace through his home of Bacon County, Georgia. “I actually sketched out a map,” she says. “I knew about the intersection of two creeks, and I found a church he mentions.”

Aside from the Ten Mile Missionary Baptist congregation where Crews’s parents were married and an older brother buried, Eby didn’t have much to go on. Bacon County, Georgia, has no memorial to Harry Crews. After all, as Eby describes it, his fiction “is full of the nastier underbelly of this rural life: dogfights and drunks, snake handles and wife beaters, the cruelty of the land and the perversity of its inhabitants hopelessly intertwined with their generosity and beauty.”

But Eby had a lead. Ted Geltner, a friend of Crews and his biographer, told her about Tom Davis, a traveling preacher and furniture salesman. And through Tom Davis, who had grown up with Crews in Bacon County, Eby found the name of Crews’s younger cousin, Don Haselden, whose father helped raise Crews after the writer’s own father died. Enter the mules.

The 69-year-old farmer had spent a lifetime training horses and mules, and now walked with a cane. “I’ve had fourteen surgeries since eleventh grade,” he told her. But his skill had won him acclaim as well as injury: the Tallahasee Democrat had celebrated Haselden’s skill in training “a particularly ornery mule named Mr. Carter—so vicious that he used to break the necks of goats and eat chickens. Haselden had adopted Mr. Carter and taught him to sit, roll over, and wiggle his ears on command.” The newspaper column Haselden showed Eby had been underlined in several places. Haselden also spoke to Eby about his famous cousin. “I just wasn’t raised with that language, but I admire what he did…. I admire Harry for what he came from—nothing, like the rest of us.”

It’s a wonderful scene, balancing the tangible facts of Haselden’s (and so also Crews’s) world with the artwork that brought Eby to them, and one of the best in her new book, South Towards Home, a literary travelogue through landscapes real and metaphorical. Eby, a former associate editor here at Brooklyn Magazine and now the features and essays editor for HelloGiggles, profiles places associated with ten Southern writers, some overlapping: Eudora Welty, Richard Wright, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, the aforementioned Crews, Harper Lee and Truman Capote, John Kennedy, Barry Hannah and Larry Brown.

“I had this crazy, rangy list,” Eby says of her initial plans for South Towards Home, her second book. “I was going to write about Walker Percy, Zora Neale Hurston.” She rattles off several more names, some famous and others less so. But narrowing the list made more sense as her work on the book commenced. “Writing a book when you are in the middle of it feels impossible,” she says.

“All the writers in the book would hate to be categorized this way”—as Southern writers—they’d want to be known as writers, period. But geography is a real, and often useful, way to organize their work. “There are western writers,” Eby says by comparison. She doesn’t speak as an outsider. “It’s impossible for me to separate my bias—I’m from the South,” she continues. “This book is a love letter.”

Eby grapples with popular descriptors of Southern writing: the gothic, the grotesque. “It’s a little exotic,” she says of how the rest of the country sees the South. “This idea of a backwards hick, a Glenn Beck conservative, a tea partier.” But she also points out the ways in which Southern culture has been co-opted, made mainstream. “There are all these tropes of Southern life now in Brooklyn. Drinking out of mason jars—back home mason jars are for children because they can’t break them. All the Southern food around Brooklyn—though very rarely is the fried chicken any good.”

The writers she follows in South Towards Home, she writes, “are the ones who spoke to me most insistently as I tried to figure out what it meant to be from the South, to answer that echoing question, What is it about this place, exactly?” The best writing about and of the South is that which practices “a kind of controlled destruction, constantly replacing the idea of the place with the concrete details of it.”

“Writing about Harper Lee was hard for obvious reasons,” she says on the patio outside of King Tai. While the only living writer Eby chose to write about, Lee is about as easy to contact as the dead. (Eby was lucky to find herself a medium—a friend of Lee’s—but was still only able to get as far as Lee’s nursing home door, where she left a foil-wrapped chocolate rabbit.) “It’s also hard to write something new about Faulkner,” she adds.

“Wright was hard in a different way,” Eby explains. “His story of place is a story of absences. It’s astonishing that there’s so little there.” There are very few black writers’ homes in the United States, she says, and none for Wright either in Mississippi, where he was born; or Chicago, where he wrote his first novel; or France, where he lived out the rest of his life in exile. By all rights, Wright should have a passel of preserved homes as thick as Edgar Allan Poe’s. “It made me think of all the people who didn’t get a chance,” like Wright, “to leave the South and write,” Eby says.

Her book title references native Mississippian Willie Morris’s memoir, North Towards Home, which chronicles how the writer and Harpers editor left Mississippi and then Texas for a life in New York. “Reading fiction is always the way I’ve oriented myself in a place,” Eby says. “It informed my life as a teenager in the South, as an adult in Brooklyn. It’s a way to navigate.”

Fiction, she says, “is more than a physical map, but it has that map imbedded in it.” Even as she navigated the real-world spaces where these writers—from Faulkner to Wright to O’Connor—Eby “felt like a place becomes a setting and people, characters.” Certainly Don Haselden (his neck full of metal pins and a trick-performing mule out back) is worthy of a great work of fiction, not because his story is exceptional but because it is true. South Towards Home, as Eby puts it, is about “the way that fictional places are real and real places are fictional.”

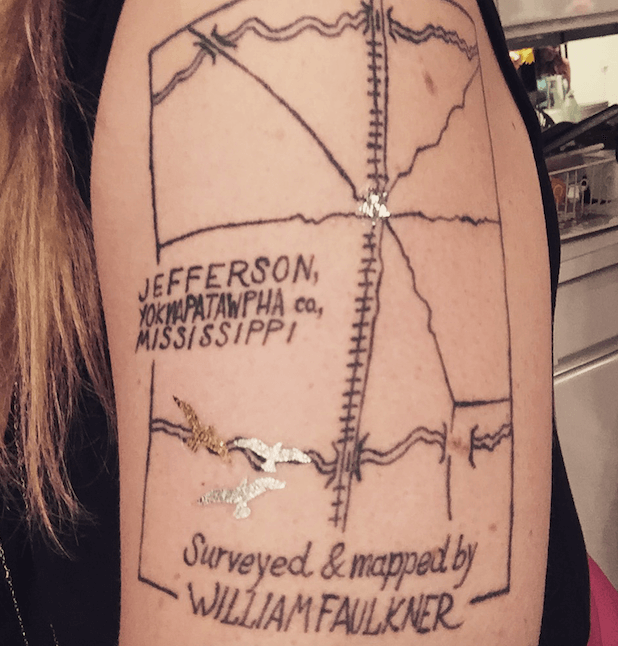

“Maps are stories too,” she says. It’s a good time to point out the lovely, and lovingly reproduced, map of Yoknapatawpha, the fictional Mississippi county based on Faulkner’s home of Lafayette, tattooed on Eby’s arm. It was a gift to herself, a mile marker, after she submitted the manuscript of South Towards Home. “It seemed like it would never actually happen,” she said. It meant that, “finally, what I was doing wasn’t avoiding writing my book.”

She majored in urban studies as well as literature in undergrad, and her lingering attachment to maps shows both on her sleeve and in her book. “Maps are there because people made them,” she says. They don’t just happen. But maps are also lies. “Useful lies,” she says, “we need them. Fiction is just another system of navigation. Both are equally metaphorical.”

Eby’s Tattoo

You might also like