Who Runs the World?: How Genius Plans to Transform the Internet

Tom Lehman and Ilan Zechory

All photos by Jane Bruce

If you want to transform the world, you’ve got to start somewhere. But somewhere is not, as it turns out, Williamsburg.

“Williamsburg is a little late-ish on the whole capitalism side,” Tom Lehman, co-founder of Genius (formerly known as Rap Genius) explains, while Ilan Zechory, another co-founder, sits next to him, laughing.

We are sitting in an apartment in one of those anonymous glass condos that line Kent Avenue along the Williamsburg waterfront, one of almost a dozen apartments in the building which have long served as offices for Genius, but which will soon be vacated when the company relocates to a 44,000-square-foot former factory in Gowanus.

“We’d been looking for new office space for a while,” Lehman says. “Gowanus has a certain energy to it… that belly fire. We want the office to be a monument to knowledge in a sort of literal way, in the way our website and our platform are a sort of monument to knowledge in a more ephemeral, mental sense.”

The move comes on the heels of Genius’s major rebranding last year, a transformation which involved the resignation of its other co-founder, Mahbod Moghadam (whose propensity for saying and doing singularly offensive things ultimately became too much of a liability to bear), an infusion of more than $40 million in capital, high-profile hirings of people like Sasha Frere-Jones from The New Yorker and Emily Segal from the trend-forecasting group K-Hole (AKA the birthplace of normcore), as well as a monumental shift in the company’s mission. No longer would Genius be known primarily for the annotation of hip-hop lyrics; rather, Genius would soon be the platform from which the whole Internet would be annotated. In short: Genius will be what we use to explain—and understand—the world.

“It’s a liminal time; it’s a transformational time,” Lehman says. “On the one hand, we are trying to branch out and take truly concrete steps to annotate the world with this new project that allows you to annotate any web page on the Internet. By the same token, we want to continue to deepen our relationship with the texts of music, with lyrics, and get even better at what originally made us hot. And trying to do both of those things is a big challenge.

“You know,” Lehman continues, “one of my favorite quotes from The Affair is: ‘Everyone’s got one book in them, almost nobody’s got two.’ And we’re at a stage now where we’re really trying to put the finishing touches on our first book, this sort of pop, bestseller, pulp fiction-y type thing, called the annotation of all lyrics and, even more than that, the sort of ultimate companion to all music, and also write this new book, which is: What does annotation mean outside of the context of music and lyrics and poetry and historical documents?”

Which, you know, good question! Or at least necessary to keep in mind, especially while listening to Lehman and Zechory and many other members of the Genius team extol the virtues of annotation to a degree where I found myself nodding along enthusiastically to pretty much everything that was said, all the while envisioning some sort of web-based utopia where it would be possible to go deeper and deeper into the multiple meanings of every sentence—every word!—on the Internet, achieving some kind of online enlightenment along the way. And—and!—it will all be thanks to the collaborative work of a global community of annotators. Picture the “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” commercial, only instead of buying anyone a soda, everyone on that sunny hilltop will be furiously annotating the Wikipedia page on the history of Coca-Cola, all the while living in perfect harmony. Even the honey bees will still be alive!

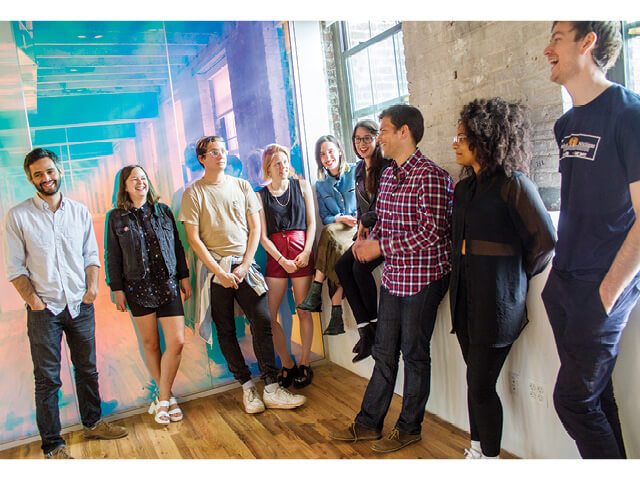

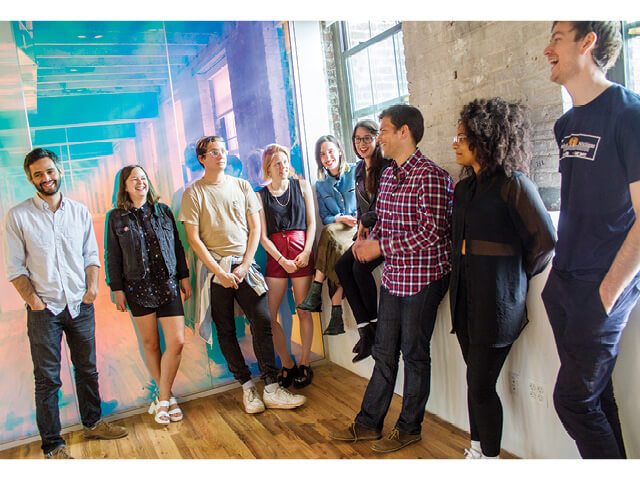

Left to Right: Max Kotelchuck, Jenn Scheer, Ezra Glenn, Lila Murphy, Emily Segal, Teresa Fardella, Andrew Warner,

Jael McCants, James Somers

Zechory explains it more measuredly. “What we’re trying to do is enhance everyone’s reading experience. Make it a little more fun. Maybe make it a lot more fun. We’re basically trying to make browsing the Internet less of a lonely experience and more of an intellectually exciting experience. We want it to feel a little bit impoverished to read a site without annotations.”

And if at that moment, someone had asked me: So, what does annotation mean for the world? Well, I just might have answered: Everything. Or, at least, utopia.

It’s easy, in other words, to believe in the Genius mission. After all, we are living in the age of explainer websites, which serve the purpose of telling readers what they should think—and why—about whatever is the hot topic of conversation of the day. So isn’t Genius’s attempt to annotate the Internet an extension of that? Isn’t this what we’ve all been waiting for? A way to see everything in a richer way, as if discovering a new dimension? Like an online version of the moment when Dorothy steps out of her black-and-white world and into the colorful land of Oz? (When I floated this annotation-as-Technicolor analogy in conversation, Lehman responded: “Totes.” Which made me laugh, though now I’m not so sure it was a joke. When you spend enough time with Lehman and Zechory, the references—to everything from a moderately popular Showtime series to the alliterative names of obscure Connecticut towns—go flying, so you start noticing jokes when maybe they’re not even there.)

Everyone I spoke with at Genius, from Lehman and Zechory to the engineers to the designers believes that Genius will facilitate both a new kind of communication as well as a new way to consume knowledge, and that it will bring new color to the Internet. Or, as creative director Emily Segal tells me, “It’s a completely new way of reading and writing. It’s somewhere in between.”

Emily Segal

Segal speaks enthusiastically about the Genius mission, saying, “I came to Genius mostly because I’m a complete sucker for utopian ideas of changing the Internet. The idea that we could carve out a new space that isn’t already colonized by the big players of the Internet, and get back to some of the original dreams of what the Internet could do for people and how it could bring people together, and change the way people think and learn, was super, super appealing to me. And I loved the way that we were building a different type of brand in the Internet space. My goal was to build the first tech brand that was as advanced as any cultural brand. Advanced in an interdisciplinary way, which doesn’t really exist in tech.”

To that end, Genius will be staging things like live annotation events (there was one this past April at MoMA PS1, during the opening of a Simon Denny exhibit), where people on a stage employ the new Genius Beta program (perhaps you’ve seen the Beta billboards featuring a giant crawling baby?), which allows people to either install Beta directly or simply to copy and paste Genius code in front of any URL, thus enabling the annotation of any page on the Internet using only a browser. This ability to annotate everything was apparently one of the original visions for the Internet, which is one reason everyone at Genius is so excited to see it brought to fruition. But while the ultimate goal—to make every page online immediately accessible for annotation, without inputting code each time—is still years off, the current dream of Beta becoming popular with, if not essential to, the online community is still in its infancy. Because while Genius.com has millions upon millions of users every month, it can still be used passively; i.e. readers might have no desire to do annotations, but just enjoy seeing what the real story is behind Post Malone’s “White Iverson.”

But for Genius Beta to really make a difference, it will take a more active level of involvement from the casual Internet user; it won’t be enough for people to just get used to reading annotations, they will also need to want to make them. This is part of the reason why Genius has made so many high-profile hires, recently including employees who can work doing community outreach in places like schools, so that the gospel of annotation can be preached to a wider audience. And it is to the same end that the company will be hosting parties, lectures, and things like the ongoing series Code Genius at the new space in Gowanus.

Jenn Scheer, James Somers, Andrew Warner

Lehman says, “What we want is to bring people to Gowanus, to Brooklyn, and have people learn stuff. And we will have Code Genius there. One event might be where engineers come and learn something about programming. Or what’s the Code Genius of literature? Or what’s the Code Genius of science? We want to establish ourselves as a cultural center in Gowanus.”

I attended a Code Genius event this spring, my first ever immersion in what I’ve long heard existed, but rarely saw evidence of in person: Brooklyn’s burgeoning tech scene. What I mean is, while the tech industry is socially and culturally pervasive in a place like Palo Alto, no matter how much I’ve heard about the borough’s thriving tech community (and despite the fact that MakerBot has offices in the same Downtown Brooklyn building as Brooklyn Magazine), I didn’t have that much personal experience with it. And then suddenly, I was right in the middle of it, which is to say, I was surrounded by engineers and coders who were all there to hear presentations about things like the physics of the photo carousel on a smartphone, and why the newest trend on Twitter (commenting on a screenshot of a highlighted line of text) is really just a clunky form of annotation for which Genius engineer James Somers has a simple, streamlined solution.

It was all fascinating to me (not least because I was so completely out of my element: for every 100 women in Brooklyn, there are about 83 men; this demographic reality was not apparent in any way, shape, or form at Code Genius that night), and served as proof that even the relatively technologically unsavvy among us (i.e. me) could find something to be interested in at an event geared toward engineers. Even though I was a novice with things like coding, it was still interesting for me to hear about new things from people who were experts in the field.

Tom Lehman and Ilan Zechory

But it also highlighted one issue that has long plagued Genius, which is the criticism that because annotation is essentially a democratic experience, sometimes that leads to, well, less than trenchant analysis of the text at hand. I know I can trust the commentary from the polymaths who work at Genius (these are the type of people who all have several friends who have been on Jeopardy!, and a good half of everyone I spoke with at Genius had at one point come up with their own versions of the much-missed Google Reader), but can I trust the annotating masses?

Sure! Or, at least, maybe! Genius has combatted this issue by employing a system where annotations are upvoted and readers wind up primarily seeing only the most useful and valid commentary. So usually any wrong or misleading annotations aren’t available, though the level of insightfulness varies. For instance, there are times when what Segal describes as Genius’s “precision engine” seems a little unnecessary, and the benefits that “come from actually leaving comments on the actual text” insignificant. Is my appreciation of the Taylor Swift lyric “I go on too many dates” from “Shake It Off” improved by learning that it alludes to the fact that Swift “does go on a lot of dates”? I don’t think so.

And yet, for every easy dismissal of some way in which Genius is not, you know, all-the-time brilliant, I can think of so many other times I’ve genuinely enjoyed and learned things from the annotations, and have come to grow excited about the new way the platform is being used, like when Genius collaborated with Electric Literature on a Charles Yu story, “Hero Absorbs Major Damage.” Electric Literature ran the previously published story complete with Genius-enabled annotations that were written by Yu in the voice of one of the story’s characters. It was the perfect example of how annotation could deepen and complement a piece, while still preserving the original text’s worth. Each version could stand on its own, and both were well worth reading.

In the same way that annotation adds another dimension to texts, the new Genius headquarters is bound to take the company to a completely different level. While walking through it this spring with Max Kotelchuck—who, as Genius facilities manager, was instrumental in every aspect of the building’s spectacular redesign—it felt like the Gowanus space was the physical manifestation of the new Genius mission. Whereas the offices in Williamsburg were nice, there was an inherent fragmentation, one that maybe wasn’t consciously felt, but which will surely not exist at all in the new office, which might be full of discreet offices tucked away behind iridescent walls, but which also has plenty of wide open common space, and the makings of a pretty sick roof deck. Speaking with Somers about it, he says, “It’s really nice to feel like you’re in an ascendent thing, a thing that has legs. When you’re moving into a new space, it’s like a metaphor for growth.” He laughs, “And also a real example of actual growth!”

Max Kotelchuck

The idea of unlimited growth is one that comes up again and again when I talk to everyone at Genius, and it’s probably the concept that sticks with me the most. Director of engineering Andrew Warner says, “What always attracted me was having something unbounded to do. It’s very motivating from the perspective of something where, if you have to solve the same problems every day, you also want to think you’re working toward this kind of crazy reinvention of the way people think about the web.”

And there is something intrinsically crazy about the Genius mission, about changing the entire feel of the Internet, by adding layers and layers of meaning in order to better illuminate the surface. Genius might, in some ways, operate in the tradition of Talmudic texts (many people have called the Talmud the original Internet), but rather than leave the annotations to only the most learned experts, it’s offering up a new vision for how we all will start reading and writing. All of which sounds rather grandiose, maybe, but so does all technological innovation, at first. And it helps that everyone at Genius feels so clearly in it together; there’s no sense of transience, of a desire to move on to the next new thing. They are in it for the long haul, which means the Internet—the world—is, too.

As Lehman says, “It’s the texture of reading and writing that we’re trying to change here and move in a new direction. There’s no endpoint. I think we’re going to be doing this our whole lives.” ♦

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like