The Magic (and Hard Work) Behind Brooklyn Public Library’s Millions of Materials

Over the course of nine months last year, two librarians at a small library branch near Orlando, Florida, checked out 2,361 books to a fictional library patron named Chuck Finley. When the fake account was uncovered in an investigation, the branch supervisor admitted that he and another employee had conspired to protect certain books from being removed from circulation.

New materials for BPL branches are purchased by a team of selectors at BookOps, a shared technical services organization that handles logistics for BPL and New York Public Library (NYPL). Inside its unassuming brick facade in Long Island City, Queens, BookOps is a 145,000 square-foot warehouse dedicated to books. Massive rooms hold hundreds of employees at cubicles, selecting and purchasing new materials, or cataloguing new items written in Russian and Chinese. Elsewhere in the building, thousands of colorful summer reading books line shelves, freshly purchased and waiting to be processed, while well-worn books whiz around a conveyor belt as they’re sorted for their next destination.

Selectors hear about upcoming books directly from publishers. “We go out to book previews, we look at reviews, and we see what the forthcoming books are,” says Rue. “So there’s some forecasting in the publishing world that we’re privy to.” Publishers put out frontlists of anticipated bestsellers, as well as midlists of books that draw a smaller but steady audience: books by debut authors, works of literary fiction, works in translation. Midlist books can sometimes gain momentum and move to the frontlist, Rue explains, citing Elena Ferrente’s My Brilliant Friend and Muriel Bradbery’s Elegance of the Hedgehog.

Then comes customer demand. “Everyone has seen a list of, you know, ‘Best titles in 2016,’ says Rue. “The most informed customers know what’s coming out. They’re reading the reviews.” Ideally, there should be one circulating copy of a book for every three people waiting on the holds list. For extremely popular books or in tight budget years, this “holds ratio” can get a little higher. When the ratio gets too high, BookOps gets an alert to purchase more copies.

The most checked-out fiction in 2016 was Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Old School and The Girl on the Train, and nonfiction was When Breath Becomes Air. The most checked-out book of all time at BPL is Green Eggs and Ham.

Last year, selectors picked more than 473,000 items for BPL, as well as more than 695,000 for NYPL and 97,000 for NYPL’s research libraries. The largest orders were for Tanwi Nandini Islam’s Bright Lines (the first selection of the city-wide Gracie Book Club), Star Wars: The Adventures of BB-8, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, and Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Double Down.

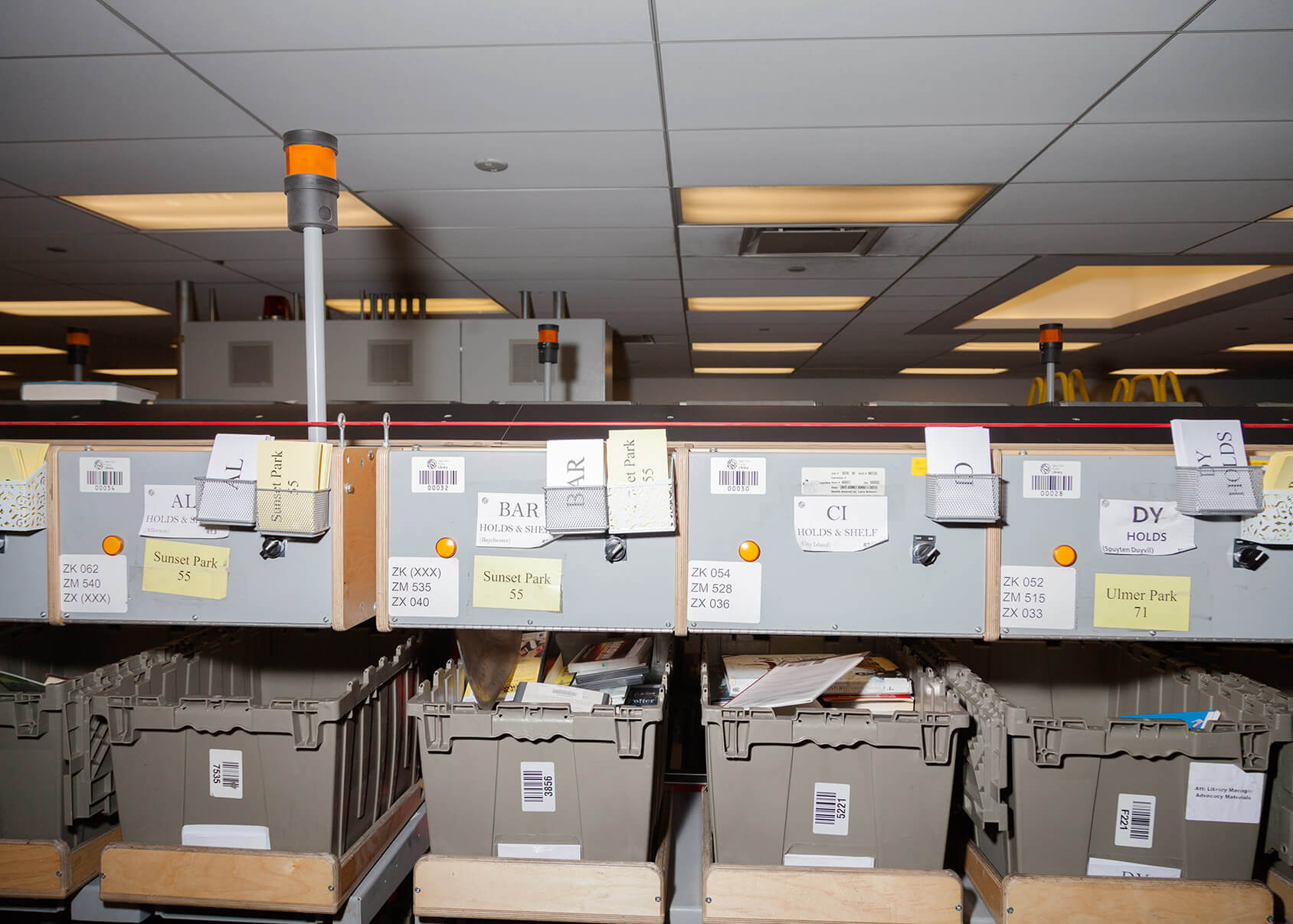

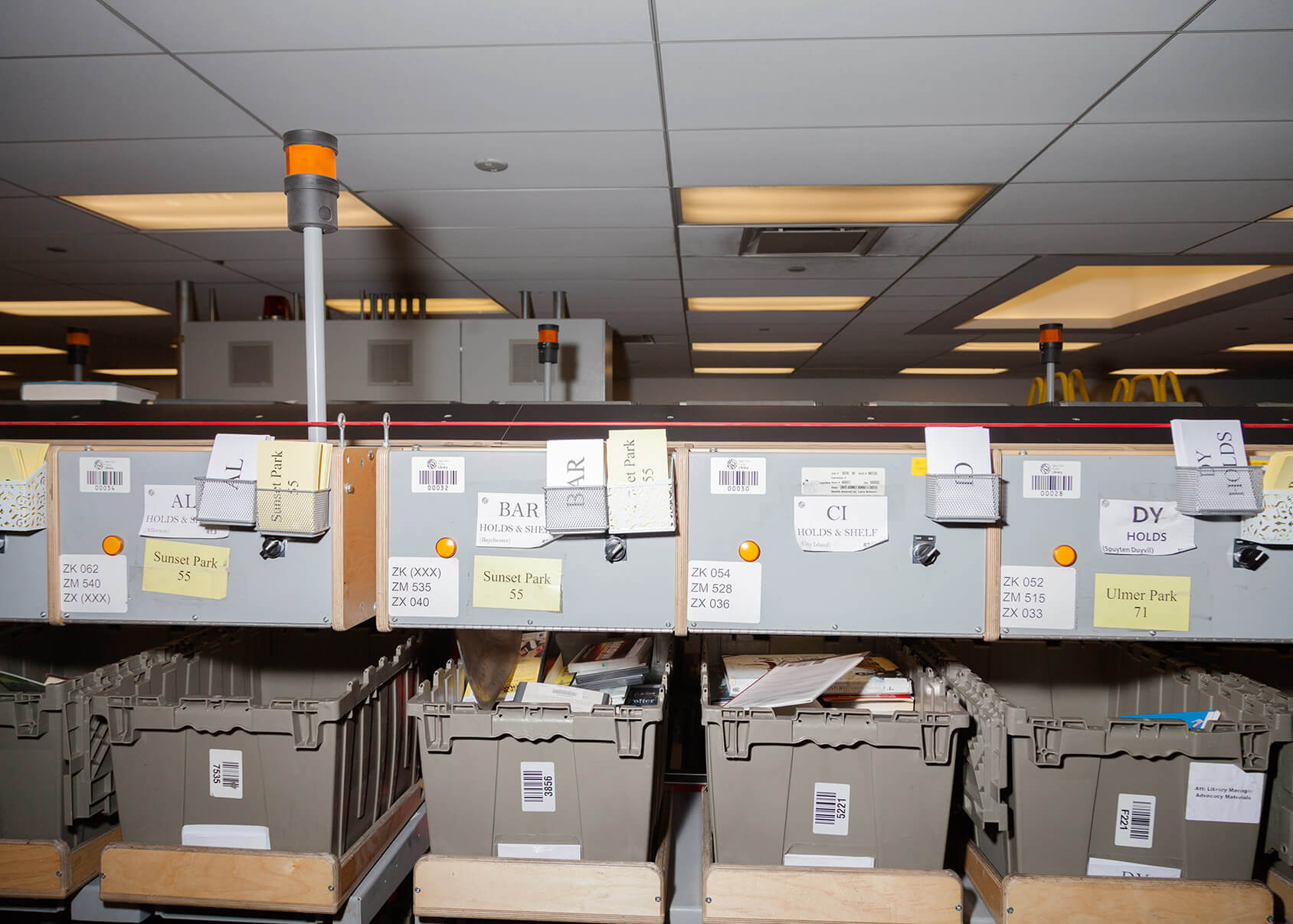

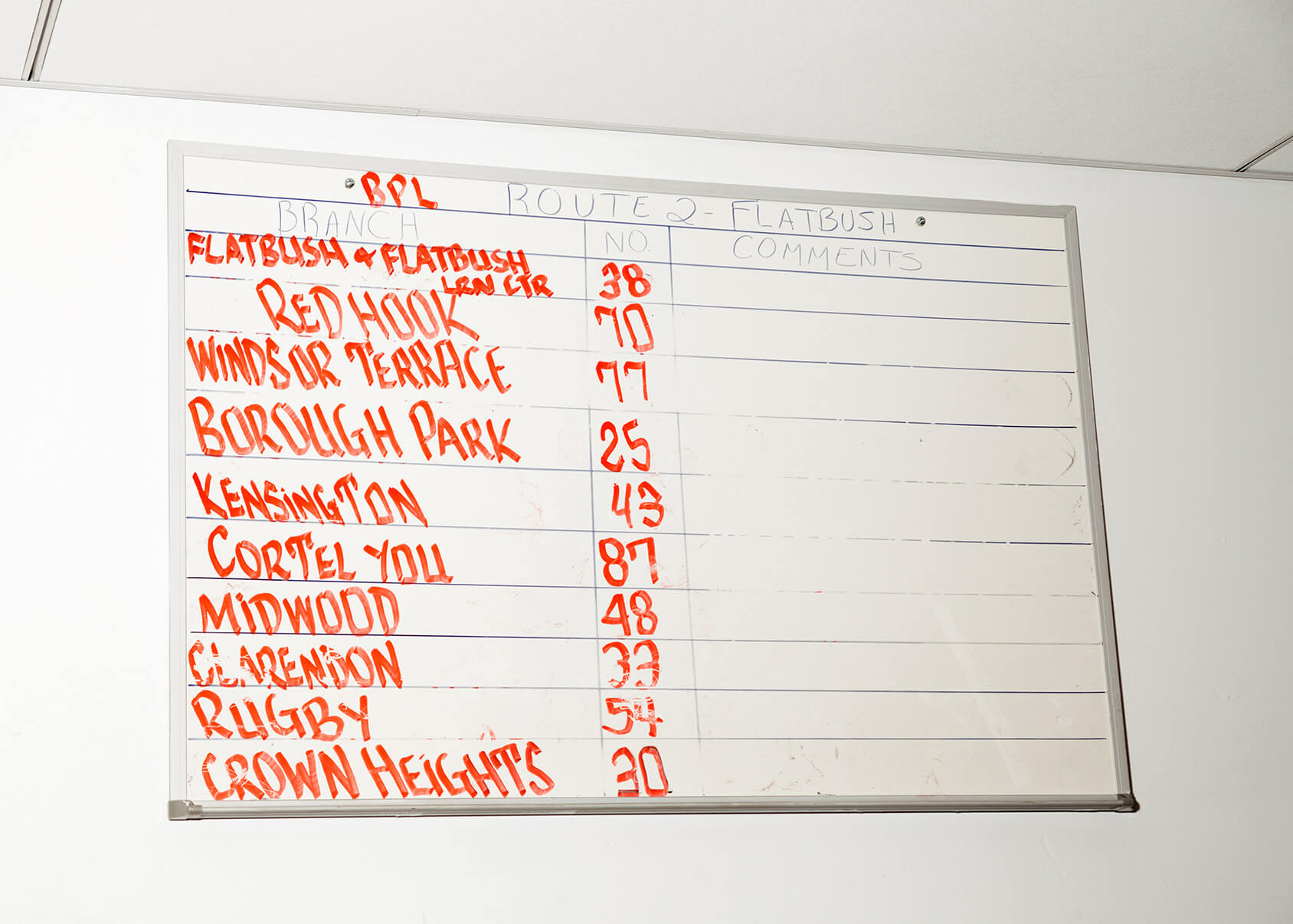

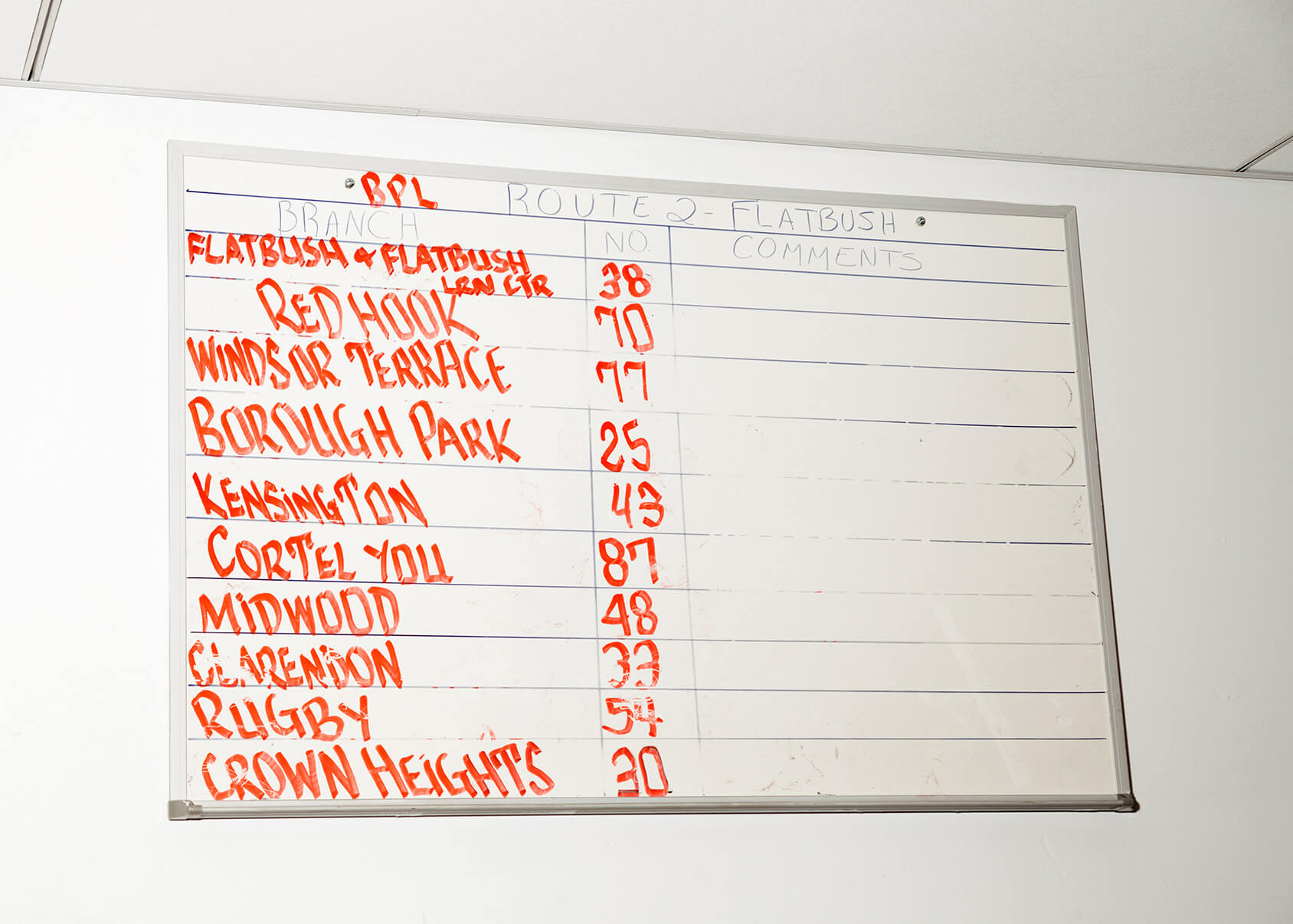

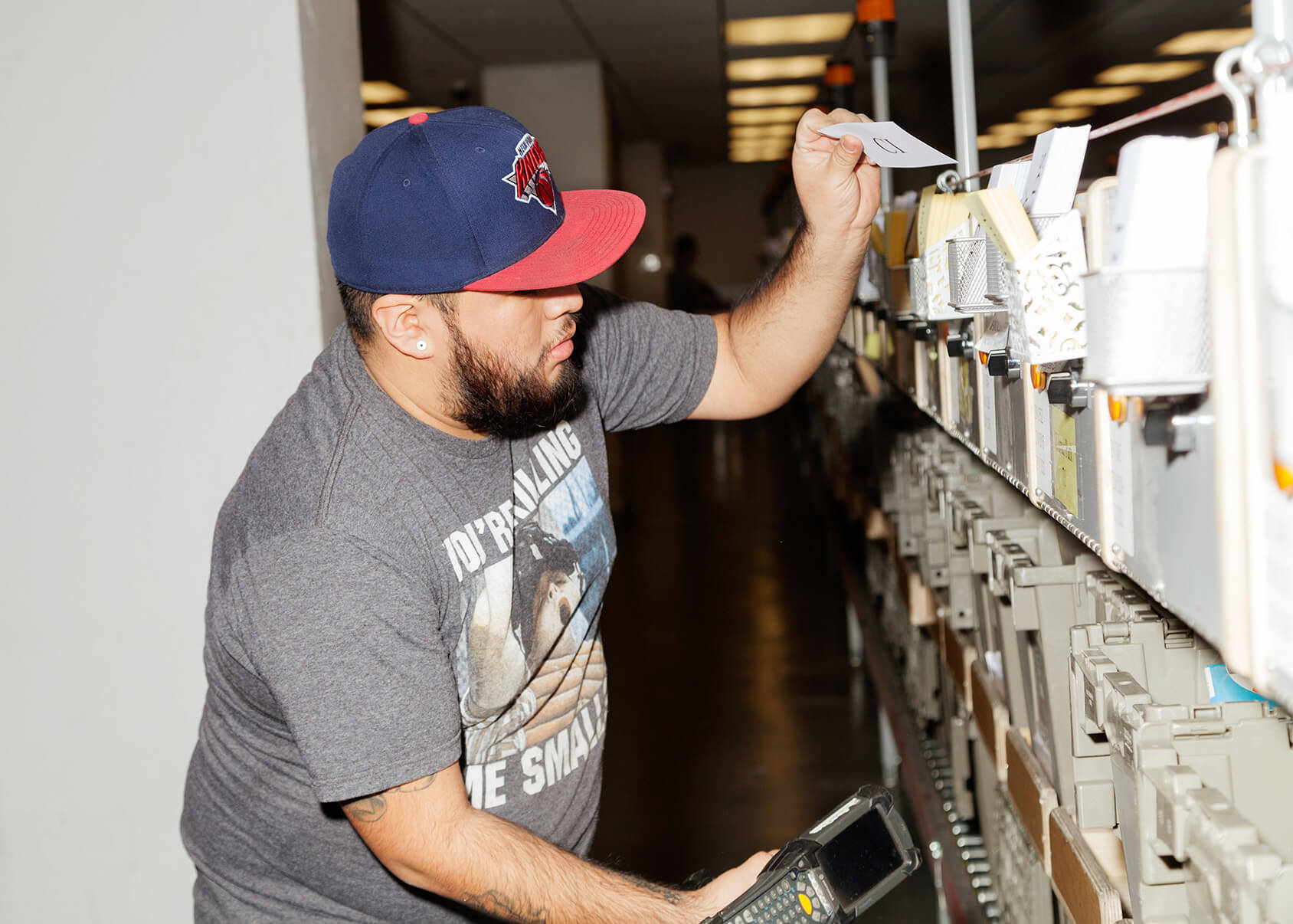

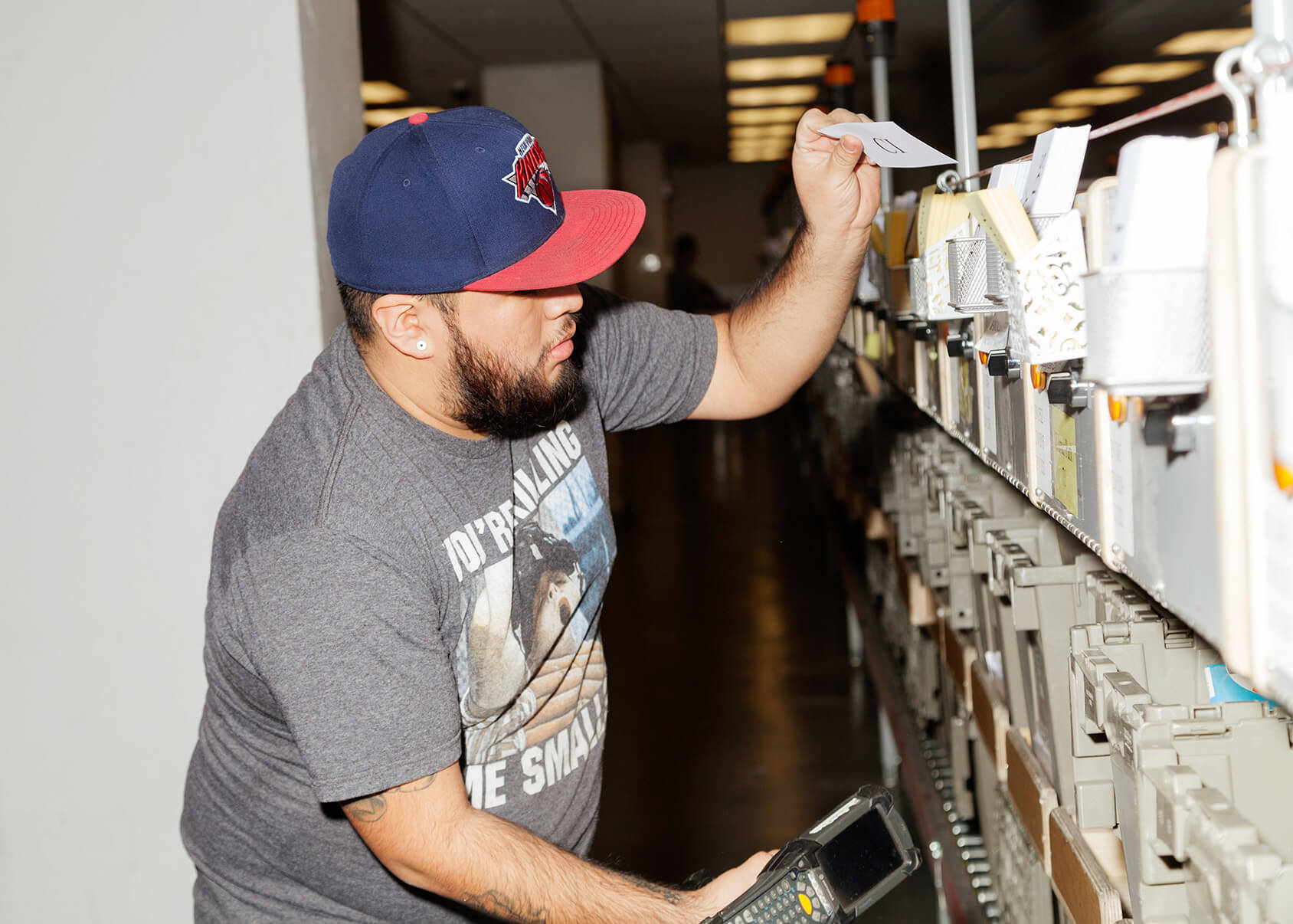

Next the books are sorted by destination. Newly purchased books, as well as any library books that have been requested at another branch, head to a massive machine called the sorter. Each morning from 7:00-8:00, employees feed BPL materials onto the sorter’s 238-foot conveyor belt. As a book zips around the belt, an overhead scanner checks it in, assigns it to a hold, and makes sure it drops into the appropriate bin.

“Every year have a contest with Seattle, who can sort more in an hour,” says Magaddino. While the timer is running, pump-up music blasts and employees from the Brooklyn and New York branches cheer on the sorters. “Unfortunately we lost last year—barely,” he says, making the record 3-2 Seattle. New York’s sorters aim to settle the score this month.

BookOps, which manages 150 locations, is the largest library technical services organization to handle everything under one roof. Magaddino says that before opening the Long Island City location, returned books took a week to sort and redistribute, and BPL contracted with UPS for branch deliveries. There was no way of knowing where books went missing.

“For example, we would not want to have a 2005 travel book to Great Britain,” she says. “In the science field, in medicine, we don’t want to be circulating old, bad information that’s been disproved. So certain things we just get rid of because we have an obligation to our patrons to have good information for them.”

“We rely on data as a help, to say, ‘Oh, this book has not circulated in two years,’” says Rosenblum. “But in all the years I’ve been in this business, I have never told my librarians to get rid of something because it hasn’t circ-ed. There are a lot of factors that go into it. We rely on the expertise of our professional librarians who are out in the branch to make the final decision.”

Brooklyn Public Library has a catalogue of 4.5 million items and is the fifth-largest system in the United States. “I am truly impressed. People read here, it’s amazing,” says Rosenblum. She sees “people in their twenties that are reading books on the subway. Old-fashioned print books. And they’re reading really interesting stuff!”

Photos by Maggie Shannon

You might also like