Interventions: James N. Kienitz Wilkins at the Whitney Biennial

Central to Wilkins’ practice is the internet. Back in 2007, he was poking around online and discovered a PDF transcript of a public hearing in Allegany, New York, discussing replacing the town’s current Walmart with a Super Walmart. This became the basis for his satirical 2012 feature Public Hearing, a rigorous “visualization” of the transcript reenacted line-for-line by the artist’s friends. It even included a five-minute gray screen representing the actual break time noted in the transcript. Shot entirely in close-ups on black and white 16mm, it’s a stylistic mash-up of Bertolt Brecht and Frederick Wiseman.

Since then, Wilkins has released a series of inventive shorts that showcase his knack for genre storytelling. Mixing high and low culture, they’ve earned him a following on the festival circuit. Among the best is B-ROLL with Andre (2015), a found-footage film inspired by hard-boiled fiction and narrated by a hooded man whose face is hidden. Voiced by multiple actors, he narrates the strange fate of his prison buddy Andre, making more than a few detours that include pitching a heist movie called eBoyz, fantasizing about Vin Diesel’s cosmopolitanism, and parsing the metaphysics of digital resolution.

Peppered with one-liners (“Gone Girl must be the whitest film noir ever”), it’s also very funny. Indefinite Pitch (2016), which played at NYFF’s experimental section last fall, is perhaps the filmmaker’s most cleverly subversive work. A 20-minute tour de force of digressive storytelling, the “film” is an extended movie pitch narrated by Wilkins in an amusing deadpan, accompanied by a slideshow of banal black and white landscape photos of his Maine hometown. Filled with arcane facts and riffs on race, Hollywood, and New England, it’s equal parts history lesson, industry satire and political monologue.

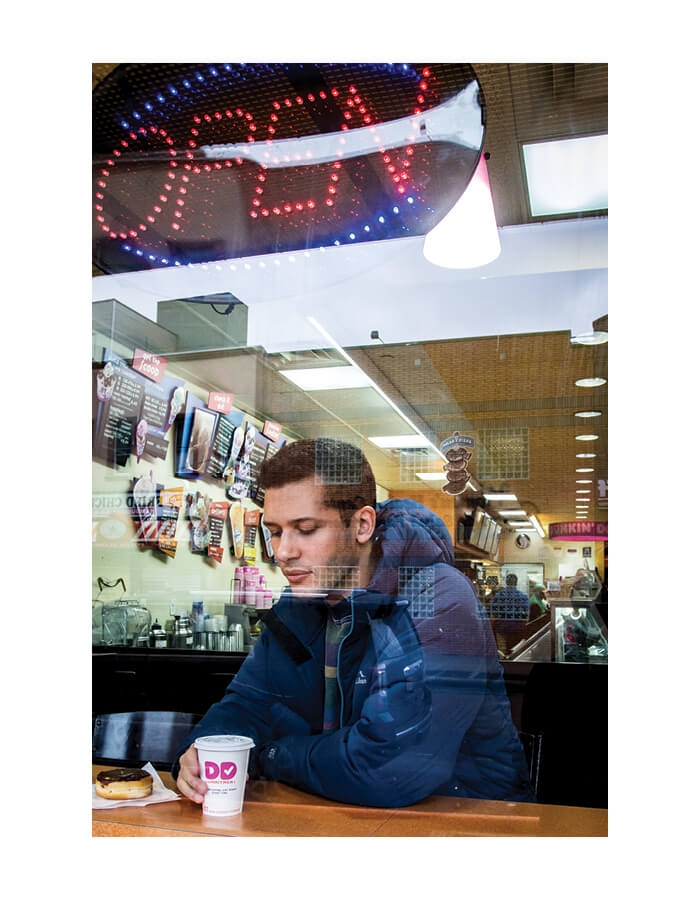

Now, Wilkins is set to unveil two new films. Common Carrier, his second feature, will debut at CPH:DOX, while Mediums, a new short, has been selected to play alongside B-ROLL with Andre at this year’s Whitney Biennial (they’ll play April 1 and 2). I sat down with the 33-year-old last month to discuss why he loves narrative, feels okay about Rihanna’s lawyers, and thinks style is a trap.

What can you tell us about the new film?

Mediums is a medium-length film, shot all in medium shots. We filmed entirely on sets, so it’s a studio movie like Public Hearing. Medium shots are the most common, like the two-shot, but their subject matter in large part defines them. The movie is about the jury selection process called voir dire, which means “to say what is true.” But the movie doesn’t take place within the courthouse. It’s sort of the proceedings outside of a proceeding. It mixes found text quotations with original scriptwriting, so again, it’s midway between what I was doing with Public Hearing and my interest in original scriptwriting. Parts of it feel a bit like a sitcom.

You also have a new feature, Common Carrier, which is a group portrait of artists all connected by you, the filmmaker. Visually, it’s pretty dazzling, because each shot is

a superimposition.

It’s two movies for the price of one! It was a weird film to edit because it was more like dealing with flow than with cuts. Common Carrier is really about 2016, just sort of the rumblings, without focusing on the specific politics. What was floating in the air like FM waves. I tried to look at the movie more as a sampling of certain viewpoints or ways artists perceive reality, than as a story about artists struggling in New York. An important idea for me is that it’s possible for characters—subjects—to be multiple things at once. In scenes where they’re performing scripts, what’s interesting to me is what it means to spend time with people who are allowing me to do this. They’re agreeing to play along. At the end of the day, it’s spatial. I see movies as maps of certain moments of time and the process of thinking that then become compressed.

For any New Yorker, the soundtrack is instantly familiar. We hear lots of Brian Lehrer from WNYC and Rihanna on Hot97.

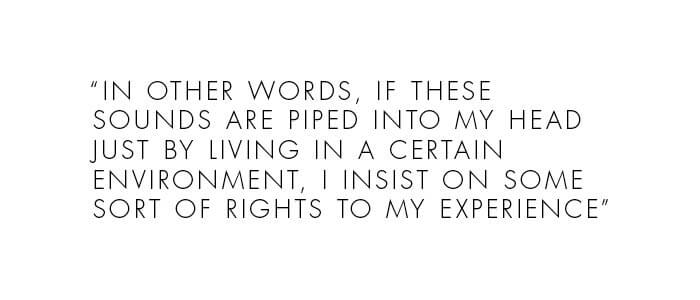

Sampling is such a part of our culture. It’s the way we communicate now. I think of Common Carrier as a mixtape. In hip-hop culture, the mixtape is a way of circumventing the legal rights of sampling. I think of my documentary intent as a sort of fair-use argument to be able to represent one’s own subjective experience. In other words, if these sounds are piped into my head just by living in a certain environment, I insist on some sort of rights to my experience. B-ROLL with Andre deals with this in a way. A bigger issue for me is what it means to make unsalable movies. I’m really curious what it means to premier Common Carrier in a festival context, where the expectation is that features get sold. In this case, it can’t be sold. It brings up bigger questions: What is a soundtrack? When are you documenting and when are you fictionalizing? It’s weird, it’s like creating this rarified thing that’s also not.

A lot of artists want their work to have a recognizable “look.” This is often about marketing.

But you’ve avoided this altogether. Each of your films employs a different format and a different formal strategy.

Voice is different from style, and they’re often confused. I feel like style is the downfall of a lot of artists. I think it’s important to resist it—not to lack style, but to resist generating a consistency at the expense of a narrative consistency. To be stylistically promiscuous is interesting to me. We’re not necessarily taught that. In this culture of self-branding and being a unified artist, it’s to your benefit to be “recognizable.” With a lot of artists, you know what you’re going to get with each new piece. To me, that’s artistically dull. Some artists that we associate with a certain style in fact don’t really have one. I was reading an interview with Almodóvar and I was happy to hear him say that he consciously tries to break his style with each new movie. Of course, he has certain predilections and taste. But it’s a goal of his to be genre-less, or to mix up so many different genres as to have created his own.

Let’s talk about money. You make most of your movies for nothing, or next to nothing. It requires a resourcefulness that seems entrepreneurial to me. But, unlike many other artists, and especially filmmakers, you’re not making products that anticipate a return.

I want to make movies that haven’t been made before, as a challenge to myself, not that I’ll always succeed. But I feel like the same is true for how to operate as an artist-filmmaker. I’m interested in money. With every single movie I make, more and more, I realize, to some degree, there’s a fixation on money. I don’t care about being rich. But if you wanted to give me a free million dollars, I’d take it in a second. And I wouldn’t get hung up on where it came from in ways that some of our liberal peers do that seem pretty false, to be honest. But it’s the personal compromise or being false to myself that I have a problem with. Frankly, I just get annoyed easily and have a really low tolerance for jumping through hoops for other people. It could even be a defect in my personality. I feel totally lucky people are starting to take notice of my work, but I’m totally fucking broke and I don’t see that changing any time soon.

In the last decade, “hybrid” has been popularized as a genre, even though mixing fact and fiction as a practice is as old as cinema itself. Your films are unique in how they mix documentary tropes and scripted storytelling. I’m wondering how do you describe your practice.

I fucking hate it when people talk about documentary and narrative as if they’re obverse sides of a coin. Narrative is not the opposite of documentary. Even “fiction” and “nonfiction” are problematic, since they mostly refer to modes of production. For lack of a better term, I often say that I’m interested in experimental narrative. I mean, narrative as a medium unto itself. If you think of experimental film as messing around with film stock, I’m messing around with narrative stuff. When I was 17, I interned for PBS and we shot a Frederick Wiseman-type piece on the Maine school system. It was funny to be a high school student shooting other kids as specimens. So, in a way, my background is cinema verité. But my interest in documentary is this weird mix of scripted material I write—creating characters out of real characters and having them play versions of themselves—and aspects of verité—just trying to figure out what’s happening in a given moment and getting coverage. In the edit, it treads into the realm of teasing certain ideological findings without necessarily going completely there.

In media parlance, “narrative” refers to power and who’s winning the war of public opinion. For you, narrative is intellectual. Maybe you can walk us through your thinking.

You have plot, narrative, and story. I see plot as the material. It’s like little points of data—information that’s ordered but raw. When people use “plot” pejoratively, as in a soap opera is “too plot-y,” it’s because it’s sort of overflowing with data. It’s a chain of things happening, but that doesn’t mean there’s intelligence to it. Narrative is intellectual because you’re essentially explaining what the plot is doing. It’s about having to take a step back and consider the different options of telling. You’re giving meaning and staking out a beginning and an ending. Story, for me, is moral. It’s about explaining the why’s. “What did this mean about me, about society?” That’s why people ask, “What’s the moral of this story?” And this is what Sundance and Tribeca traffic in—moralizing—and why they’re so obsessed with story in documentary. They want to begin with that. They want to start with the moral without looking first at the raw data. To me, narrative is where it’s exciting. It’s not arbitrary, like plot, and it’s not ideological, like story, but it deals with time and limits.

Aside from economic instability and a hostile political climate, what are the biggest obstacles as an artist?

Not being hung up on just making stuff. Not waiting for permission to do things. I mean internally, too. Stop thinking about movies as product. I don’t even mean, “The art comes first.” With digital culture and people becoming successful in all these random ways, we’re surrounded by lessons that the things that we think are not the product. Anytime someone says, “No, you’ve got to do it this way. This is the product,” they’re almost always wrong. Just because you’re a filmmaker doesn’t mean the thing you’re selling are your films. It could be ideas. Or it could be a sense of resistance.

So, what’s the ideal scenario for you?

This is the ideal scenario. I’m living it. Last weekend, my girlfriend and I were driving to Trader Joe’s in Flushing and the sun was setting above a Home Depot. To me, it was a beautiful sight. The way it was glowing orange and there was a fiery rim above it and there were these moody clouds and these scrappy woods nearby with train tracks. This is my scene. There’s so much potential. I mean, it seems so stunted, but it’s what we’ve inherited.

Photos by Jane Bruce

You might also like