Brooklyn 100 Influencer: Aaron Foster, Foster Sundry

Good food does not have to be snooty. That is what Aaron Foster has shown us with the opening of Foster Sundry a little over a year ago. After more than a decade in cheese (wherein he headed up cheese-buying at the city’s most revered cheese institution, Murray’s) and as Head Buyer at The Brooklyn Kitchen in Williamsburg, Aaron has now introduced the best of the best in groceries to Bushwick by tapping into his long-cultivated and extensive network of producers around the world. With his singular offerings and welcoming hospitality, he has grown an authentic and dedicated community of customers around him, interested in learning about and experiencing all of the best stuff—without the customary pretension—too.

You opened your own place over a year ago. Congratulations! What have you found to be the biggest challenge, and the biggest reward in making this happen?

Thanks! The biggest challenges were mostly the obvious ones. One of the biggest is just getting the doors open. There are so many obstacles to even that modest accomplishment: complying with city, state, and federal agencies; wrangling contractors; finding, hiring, and training staff; and just finding your sea legs as a business. With the doors open, it’s really just staffing and cash flow. There is never any stasis or equilibrium with staffing. There’s always something in flux that needs attention: someone calls out sick, someone quits or is fired, new employees need training, existing employees need re-training, people sleep with each other, people break up, they move, they get bored. Not a week goes by without some serious staffing issue that needs addressing, and anecdotally, we have it better than most. And then, of course, there’s cash flow. Margins in our business are razor thin. We are stuck between rising labor and product costs, and a desire not to raise prices. We exist and try to thrive in that liminal space.

As for rewards, making something wholly notional and aspirational into something real, brick and mortar, is incredibly gratifying. Having something you can be proud of, that represents you and your values, that people seem to “get”—that’s huge. Eventually, I hope for some more tangible rewards (read: a salary), but for now, it’s this. My most joyful moments are the ones where makers come to visit us, and get to see the respect and pride with which we treat their products, and how that’s conveyed to our customers.

As you’ve said, you cannot offer the cheapest produce and groceries at Foster Sundry, but through years of building extended networks of the best farmers and producers around the word, you can offer the best products available anywhere. Talk a little bit about why it is important for you to offer that service, and how you strike a balance between that goal and continuing to be accessible and welcoming to the entire community.

I have a long history in the grocery biz. I’ve been doing this since my junior year in college—so, not to put a number on it, but nearly half my life. I’ve watched consumer attention drift from gourmet to organic to local to sustainably raised to traceable to authentic to whatever the fuck soylent is. Remember when everyone used to talk about food miles, until they remembered they really like olive oil? All of these issues are valid points for discussion and part of a larger conversation about the complexity and transparency of the food system. I mostly blame the media and the constant churn for new content for moving the spotlight from one buzzword to the next.

My approach in putting together my shop was this: trust my palate; prioritize value; work with friends; don’t compete—offer an alternative. I put things on the shelves that taste good to me. I stand by my products, and there’s a reason for everything that’s there. I look for value wherever possible. There’s gotta be 50 different shitty, twee jams made in Brooklyn and selling for $14 a jar at the Flea. Just because it has a bird on it doesn’t make it good. I look to highlight products that are excellent, especially for the price. Value just means the ratio of price to quality. A lot of specialty shops curate shelves full of beautiful, expensive shit that doesn’t taste good. We certainly carry some pricy items in the shop, but we carry them because I think they taste fucking fantastic, and because I think they’re worth it. Not everyone will agree with me, but at least it’s a reason other than that “it’s pretty”.

Another goal of opening my shop was to be able to support my friends. Giorgio Cravero matures some of the best Parmigiano Reggiano in Italy, but I was never able to carry it at Murray’s Cheese for political reasons. Now, I get to feature him front and center, and watch him beam when he visits.

Finally, we’re not a grocery store, really. We’re a specialty shop. There’s a grocery store down the street and a bodega on every corner. Item to item, we’re never going to compete with them on price. Instead, we offer things you can’t get other places. Carefully sourced, sustainably raised grass fed meat; the best parm in Italy, Parlor coffee, etc.

What have you found to be most satisfying about your work?

Without a doubt, the hospitality side of things. Getting to know our customers, watching them get married, have children, etc. Being there for them in moments of crisis and joy. And teaching them that good food doesn’t have to be snooty or condescending.

What have you learned that you could not have foreseen going into this endeavor?

Opening a shop is far more expensive, more mentally and physically taxing, harder on a marriage, than you could possibly imagine. And no matter how hard you try, you can’t make everyone happy. I’ve learned to be less dogmatic, to be willing to pivot, and always to keep my powder dry.

In the past decades there has been significant interest and growth in the slow food/local/grass-fed/whey-fed (i.e. responsible farming) movement. When it comes to people shopping for these products in general, what are the most important factors they should be aware of that make the greatest impact on the environment, and that would help them be most supportive to the farmers/producers behind them?

Above all, it’s about trust. Find a retailer you trust, talk to them about your food. If they seem full of shit, or if it seems fishy, or if it just doesn’t taste very good, go somewhere else. And if it seems too cheap to be the real deal, it probably is.

Learn more about this year’s 100 Influencers in Brooklyn Culture.

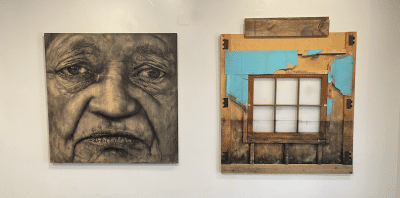

Photo by Nicole Fara Silver

You might also like