Duality, Opacity: Under the Sun

What became increasingly apparent to me as I watched Under the Sun, and as it continued to drift further and further away from something along the lines of what I’d imagined it would be, is that it is quite certainly one of the most bizarre and multivalent films I’d ever seen. While not showing you very much, it somehow shows you a great deal. While it tells you very little, you wind up gleaning quite a lot. Far from a standard-issue documentary of informational virtue, say, with a flash of verve, Under the Sun is instead part inverse fairy tale, part departure from script, part documentational relic, part shot from the hip, part record of falseness and tedium—and all enigma wrapped tightly within a rare form of propagandistic simulacrum. This latter notion is perhaps not surprising at all, actually, given that the film was shot in North Korea.

All that said, Under the Sun is still quite a simple piece in almost every visual and narrative sense. It is also very lovely in many instances, and consistently touching. Focusing primarily on eight-year-old Lee Zin-mi and her parents, the documentary follows this real family through what isn’t really the normal course of their domestic lives, and into what aren’t exactly their real places of work or study, to depict certain salient stages in Zin-mi’s ascendance, as it were, into the much heralded Children’s Union, the joining of which seems to also mark the moment when North Korean kids are encouraged to renounce for good their grip on childhood. So you’ll see the Lee family having a meal, engaging with peers and colleagues, visiting sites of reverence, and working, studying or listening to lectures—or rather, being lectured at. And all of this is what it seems, in a way. But as I’ve suggested, it’s also not what it seems.

Ostensibly commissioned to craft a portrait of a ‘typical’ Pyongyang family, Russian director Vitaly Mansky—who seems to have himself proposed the idea to North Korean authorities and had it, however bafflingly, approved—does more or less that from start to finish, according to how censors and government handlers have scripted everything. Yet at the very same time, Mansky also manages to do precisely the opposite—or rather, he simultaneously ‘shows’ you the flip side of what you’re seeing. And his method isn’t complex at all; he achieves this patent duality by merely leaving the camera rolling, and by editing the scenes to include that which is scripted and that which isn’t. A bit of information about what’s ‘real’ occasionally appears in chunks of text at the bottom of the screen—some of it quite alarming, such as a line suggesting that people never actually leave or enter certain schools and factories—but for the most part Mansky, much to his credit, lets the imagery and subjects’ physiognomies do most of the narrating. What’s scripted is of course obvious, and what Mansky ‘shouldn’t have’ shot, or what never would’ve made it by the censors, is clear as well. Everything else you need to know comes out in the all-but-rolling eyes of the ‘actors,’ in their oft-furrowed brows, in their feigned enthusiasms, in their confusion over why it matters for them to say “workshop” instead of “factory,” in the glances of disbelief they cautiously shoot at one another, in their utter discomfort in seemingly well-appointed rooms that are actually freezing cold, in their palpable fatigue with the whole charade, and not least in their tears that come streaming down in most poignant moments.

Rather than beauty, here it is repression that’s in the eye of the beholder, and your most direct mode of ‘seeing’ it is by reading it in the eyes of the repressed—those whose lot it is to behold it. As for the repressors, they’re both omnipresent and nowhere to be seen. The Dear Leaders of North Korea have long been keen on dictatorial controls, authoritarian opacities, societal steering and powers far beyond reprove, and they’ve done quite a thorough job of constructing an anomalously isolated cipher of a nation around and unto themselves. The implicit warning in Under the Sun, then, might be that leaders with kindred keennesses are elsewhere to be found, too.

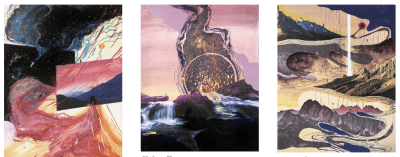

[Image courtesy Icarus Films and Film Forum.]

You might also like