What Author Darryl Pinckney Has to Say about Nazis

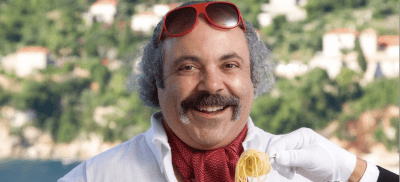

The second question asked of Darryl Pinckney, the critic and novelist (most recently of Black Deutschland), at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s March 15 Eat, Drink, and Be Literary event is about Nazis and Donald Trump. As if on queue, a woman faints. Pinckney, on a raised platform with Deborah Treisman, fiction editor of The New Yorker, stands; murmured conversation wafts up from tables cluttered with carafes of wine, biscotti, dinner plates in the process of being cleared. A doctor materializes from the audience; EMS are called. Poet and assistant director of the National Book Foundation, Leslie Shipman, leans over to whisper that this is only the second time this has ever happened in her eleven-year tenure. All in all, it’s not a bad track record.

In its twelfth year, the Eat, Drink, and Be Literary series—hosted by BAM and presented in partnership with the National Book Awards—offers its audiences a chance to share a meal, and a conversation, with a prominent author. “Our reach is expansive,” explains Violaine Huisman, BAM’s director of humanities: the program harnesses the institution’s power on behalf of great writing. Each season’s slate of authors “is our way of saying, these are the writers you should be reading this year.”

This year has already brought Booker Prize-winning Marlon James, poet and one-time presidential candidate Eileen Myles, novelist and essayist Zadie Smith, MacArthur fellow and fiction writer Yiyun Li, and Karl Ove Knausgaard, who Tao Lin once described as “a thin strong elf with silvery hair” —with photographer and memoirist Sally Mann as well as writer and literary agent Bill Clegg still to come. Four events sold out before tickets even went on sale to the public, Shipman says. The seats were all snapped up by members.

Tonight Pinckney reads from his new novel, his first since 1992’s High Cotton. He professes nervousness before he leaves the dinner table, but once he is up on the dais the pretense evaporates. He has full command of the room. “I’d become that person I so admired,” he reads, “the black American expatriate.”

The narrator, a young gay man fleeing middle-class Chicago for West Berlin in the early eighties, is fresh from rehab. He seeks a haven from his former alcohol-soaked haunts in the apartment of his cousin, Cello, who married a wealthy German. She will not let the narrator near her children, she instructs, until “he had the AIDS test.”

In the discussion he and Treisman have after his reading, Pinckney reflects on the subject matter. “This seemed to be a part of the black intellectual experience—getting away.”

Treisman asks him if he ever felt “that sense of constraint” that might come from having one’s writing read as representative of a community. Pinckney’s answer is short and direct.

“No,” he says. “The constraints are on the side of interpretation.”

“The thing about black history is that it’s not abstract,” he continues. “There’s no separation” between what you are and what you represent.

“The best fiction we return to with the questions we ask of history. Real things”—the work that can answer those questions—“survive.”

He tells stories about admitting to his parents to an arrest for smoking pot on the street at 54. “They really chewed me out—if you know my parents you’d know that bravery was pointless.” About learning German while growing up in a primarily Jewish suburb of Indianapolis. “You kept it to yourself—German was a secret.” About his grandfather’s nearly successful attempt to conceal his jazz musician brother’s memoir. About the poets he reads. “I really love Sir Thomas Wyatt—somehow it explained everything that went wrong in school for me. I love Frank O’Hara, that feeling of New York.”

It’s this kind of intimacy that testifies to the success and longevity of Eat, Drink, and Be Literary. Shipman’s favorite events follow a similar template to Pinckey’s—heavy on spontaneity and surprise: a sing-along with Eileen Myles, Denis Johnson in socks and sandals, Fran Leibowitz railing against anti-smoking laws.

The woman who fainted eventually comes to and is escorted out by EMS. BAM’s executive producer, Joseph V. Melillo, redirects the conversation to Pinckney’s work in the theater, in particular with director Robert Wilson. But Pinckney wants to talk about Nazis, or rather the primary contests that inspired the comparison. He’s blunt, funny, and unabashedly partisan. He has a candidate (Hillary, the “grown up” in his words) and wants the audience—his fellow dinner guests—to know it. He breaks one of the cardinal rules of appropriate meal-time conversation, but the evening is all the more thrilling for it.

You might also like