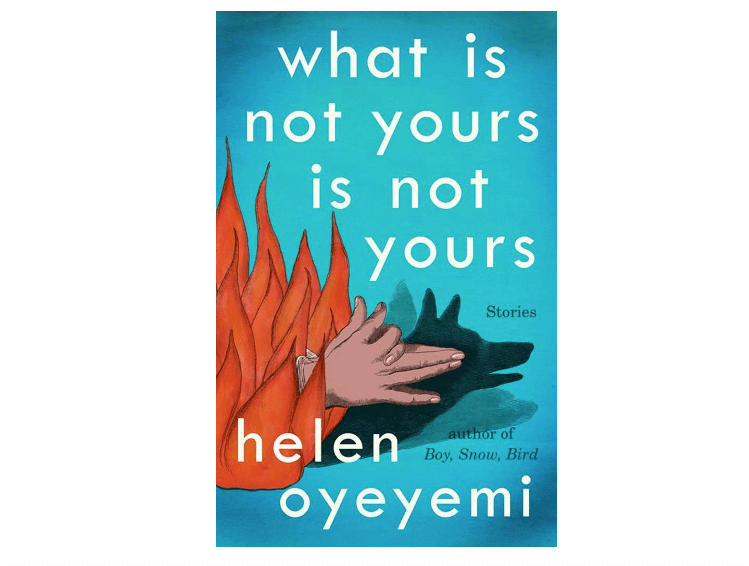

Helen Oyeyemi Is a Miracle You’d Better Appreciate

I remember the horror and shock register in my body when in high school a friend told me he was sick of ice cream. He had spent his summer scooping it. I can imagine the similar horror any reasonable book lover would (must) feel should any book critic admit to similar exhaustion. I have not fallen out of love with ice cream, dear readers, but the fact of the matter is that there are so, too, many books for any one human being to reasonable handle. This is generally a great thing—so many books!—but it’s also exhausting—so many books! Any book (and I am #blessed to encounter many) that makes you forget this cruel and impossible ratio of pages to hours to human life is a small miracle.

I don’t mean to mince words. Helen Oyeyemi’s latest book, her sixth and first collection of short fiction to date, is a big ass miracle. There is no other fiction writer working in English, save Toni Morrison, whose books I look forward to more, whose words I gulp down like someone famished. She is, for me, the real thing.

What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours is, like Oyeyemi’s previous books, invested in the fantastic. Having worked with traditions from Yoruban mythology (The Icarus Girl) to the Brothers Grimm (Boy, Snow, Bird), Oyeyemi does not here focus on a particular story or body of lore, though familiar outlines (Beauty and the Beast, Little Red Riding Hood) emerge. Made up of nine interlocking short stories—keys even figure into the title page design—the book ranges across time and space, landing as often in Prague, Oyeyemi’s current home, as in London, where she grew up. All but three stories share, at least in passing reference, the same cast of characters, the same world of contemporary-ish Europe. (It’s a place modern enough for YouTube, but also magical enough for sentient puppets, Hecate-invoking curses.) Oyeyemi builds a web of associations across families, coworkers, tenants, classmates, lovers.

The collection opens with “Books and Roses”—about, in part, a locked away rose garden. It’s one of the book’s few unconnected stories, as cloistered and lovely as its central image. Set in pre-Spanish Civil War Barcelona, a young black woman named after the Virgin of Montserrat works in the attic laundry rooms of Antoni Gaudi’s Modernista masterpiece, Casa Milà. There is little explicitly supernatural here, just memories with discrepancies, stories left unfinished, and images (keys, roses) that take on a totemic power. Even though it’s rooted in a recognizable world—in fact Casa Milà’s attic laundry is now the building’s visitor museum—it’s dreamy in the way I’ve come to know and expect from Oyeyemi’s work. In a 2014 interview with The Believer, she explained, “I see all mythology as one tradition, a way of disseminating knowledge that must come to us in a code so that we can live sanely with it, since some forms of knowledge are too dark, or too complex, to be plainly spoken.” Nearly everything she touches takes on the power of folklore, the forms of a code hinting at something bigger.

There are so many reasons I love Helen Oyeyemi. She clearly cares about stories, both creating new ones and interrogating (or plain employing) old ones. I love her facility with the fantastic; her complex, watchmaker-like structures; her keen eye for social mores. But most striking for me in What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, in part because of its large cast of fictional characters, is the effortless verisimilitude with which Oyeyemi depicts the people who make up the world. Her characters have a truly diverse array of names and geographic histories and religious beliefs and sexual relationships and family structures and gender identities—the kind of mix, you know, that actually exists in real life. It is the opposite of demonstrative, and I am ruining some of the magic by calling attention to it. In the stories they are all part of the warp and weft of the text: a detail among many other details, unsensational, unremarkable. In this, I suspect, Oyeyemi is merely recording the world she sees. But for me, it’s a policy at once unthinkingly simple and genuinely radical. Though it’s full of ghosts and tree spirits, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours is also one of the most realistic books, because of these characters and relationships, I’ve ever read.

Some of Oyeyemi’s moves are less subtle, but no the less successful for it. In “A Brief History of the Homely Wench Society” Cambridge student Day, embarrassed she cannot supply an idea for her secret misandrist student group’s newsletter, suggests they raid their rival organization’s library. “I’m betting,” she says, “The Bettencourters don’t have many, or maybe even any, books by female authors on their bookshelves. And speaking collectively we don’t have that many male authors on our own shelves.” She adds in explanation: “I want to read everything.” What follows is a genuinely thrilling passage to read—a canon swap:

“Not having read any of the books she was taking, Day made her exchanges based on thoughts the titles or authors’ names set in motion. She exchanged two Edith Wharton novels for two Henry James novels, Lucia Berlin’s short stories for John Cheever’s, Elaine Dundy’s The Dud Avocado for Dany LaFerrière’s I Am a Japanese Writer, Dubravka Ugresic’s Lend Me Your Character for Gogol’s How the Two Ivans Quarreled and Other Stories, Maggie Nelson’s Jane: A Murder for Capote’s In Cold Blood, Lisa Tuttle’s The Pillow Friend for The Collected Ghost Stories of M.R. James.”

This is, I like to imagine, a peek onto Oyeyemi’s own shelves. It also suggests an omnivorous style of reading. (Day, after all, steals the Cheever for herself.) The goal here is not canonical replacement but true integration, synthesis. It’s testament to Oyeyemi vision of the world, and vision too for the future of literature.

Helen Oyeyemi’s writing is an ice cream flavor I could scoop forever. What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours is a moving, expansive, and imaginative addition to her body of work—the equal of any of her novels. With six books under her belt and more than a decade in the literary world, Oyeyemi’s biography has no shortage of recognitions. But where, I wonder, is her major prize? I can think of no good reason why this tremendous novelist has yet to be recognized by the Booker, by the Orange Prize, the Costa: they have had both the time and the opportunity. (Alternatively, let’s give Oyeyemi American citizenship and hand over a Pulitzer, a National Book Award.) Helen Oyeyemi is among our very best. Get on it.

You might also like