Laura Poitras’s “Astro Noise” at the Whitney: A Penetrating Essay on a Palsied World

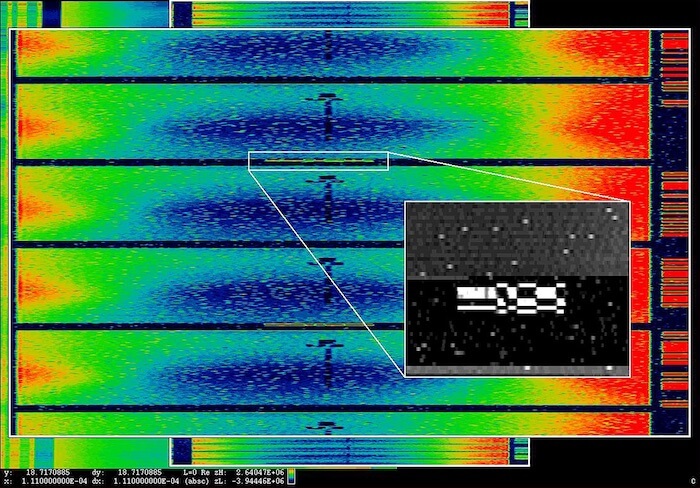

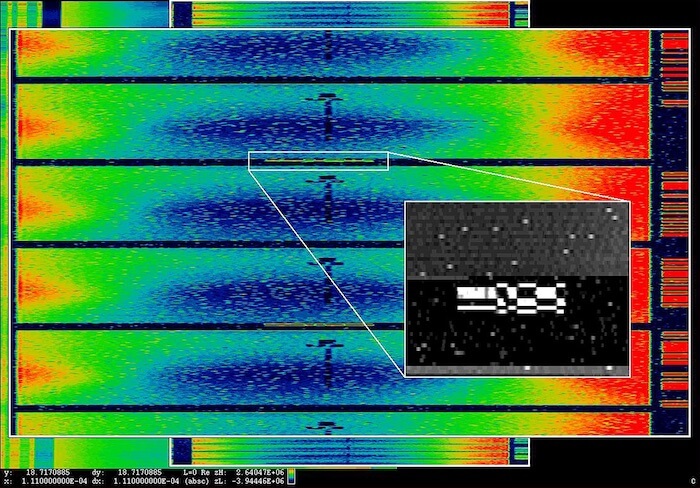

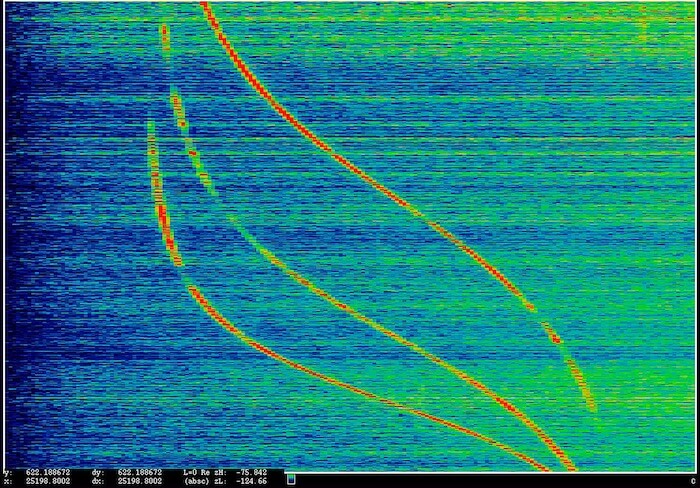

Laura Poitras, ANARCHIST: Israeli Drone Feed (Intercepted February 24, 2009), 2016. Pigmented inkjet print on aluminum, 45” x 64-3/4” (114.3 × 164.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist.

Laura Poitras: Astro Noise

February 5-May 1 at the Whitney Museum of American Art

In 2014, American journalist and filmmaker Laura Poitras released a straightforward, deftly arranged, and soberly inspiring documentary about National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Edward Snowden. Since the substance of his revelations about the NSA’s electronic surveillance was already known, the big story consisted of Snowden’s character and journey. Citizenfour convincingly erased any notion that he was a techno-geek with a messiah complex, instead presenting him as a decent, highly intelligent, and unusually resolute young man who saw past his job and its putative justifications to how it could taint American society, and felt morally compelled to act. It was wrenching to see him come to the realization, during his days in limbo in Hong Kong, that the campaign he had undertaken stood to ruin the life he’d planned. As the documentarian, Poitras didn’t grandstand or make herself the story; what she had was access, and she exploited it just about perfectly.

She has brought the same virtue of modest incisiveness to her galvanizing and appropriately disturbing first solo exhibition “Astro Noise”—the term for the thermal residue of the Big Bang and the name Snowden gave to the encrypted file he passed to Poitras documenting the NSA’s massive post-9/11 surveillance program. In a series of installations, she intends to foster an immersive and interactive viewer experience. She is unequivocally successful. There is no po-faced agitprop here. Instead, the artist drops viewers into an ethical maelstrom and prompts them to balance the atrocity of 9/11 and other terrorist attacks against the abuse and torture of terrorist suspects, the operational convenience and economy of drone strikes against the terror they wreak on untrusted populations, and the intrusiveness of comprehensive monitoring and continual suspicion on friendly ones against the state’s responsibility to keep the homeland safe. Poitras does not analyze or sermonize, and offers no explicit arguments—just carefully calibrated, visually inventive representations of facts that demand consideration.

The first video installation of a tandem titled O’ Say Can You See, displayed in a darkly painted unlit room, is a video of people witnessing newscasts of the 9/11 attacks in a public space, tracked with a solemnly surreal reworking of the national anthem. Their expressions, captured slow-motion and in lush color, encompass bewilderment, bemusement, concern, shock, horror, and resignation, but all are subdued and attenuated by the self-preservative numbness that arises in the immediacy of vicarious trauma. The urge to comfort hovers but has not yet landed, remaining subordinate for now to morbid fascination and the need to comprehend just what has happened. This footage pulls viewers in and takes them back to a moment that changed the world.

On the reverse screen, they are taken to what Vice-President Dick Cheney infamously (yet approvingly) called “the dark side.” This video, shot in black and white, chronicles part of the November 2001 interrogation of al-Qaeda suspects. It starts non-violently in a dark stone room in Afghanistan, then grows increasingly confrontational and coercive, as bright lights shine on the detainee and the interrogators physically converge on him. He struggles to pray. Then a bag is placed over his head. A frame indicating [Tape End] abruptly appears, the baleful implication being that the interrogation did not end at all. The video cuts to Guantanamo Bay, where another prisoner has been transferred. Armed US soldiers chain him to the cell floor, whereupon he is asked leading questions: “When did you join al-Qaeda?” He denies that he did. The interrogator threatens to have the man’s wife detained in Pakistan unless explains why missiles and documents were found in his car. Broken into discrete scenes that leave aching uncertainty, the clip invests viewers in the prisoners’ fate, and makes it hard for them to tear themselves away.

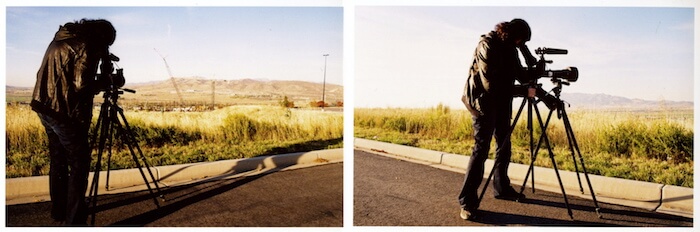

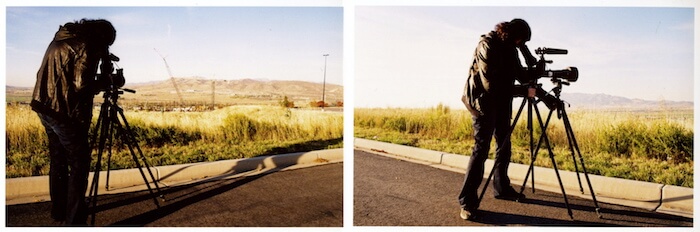

Laura Poitras filming the NSA Utah Data Repository construction in 2011. Photograph by Conor Provenzano.

In the next room, for the multimedia Bed Down Location—the expression for a drone target’s place of rest—the locus of Poitras’s interest moves from claustrophobic cell to the troposphere. Clear night skies seen from Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen—prominent fields of “targeted killing”—are projected overhead on a large square screen. The image elevates from a kind of courtyard to mere sky with moving clouds, then dips down to bushes close to the same structures. They become closer and more illuminated, as drone or fighter targets would. What looks like a drone wing impinges on the clear night sky from a corner of the screen. Daybreak brings a silhouetted drone, moving across the celestial expanse. There’s a black dot in the center of screen, then tracers. Day yields to night. Dense smoke occludes the sky. A bright ball descends towards the courtyard. No explosion is shown. All the while staccato radio traffic, the even-keeled voices of drone operators, and the whooshes of drones themselves echo in the background.

That war obscures and poisons natural beauty isn’t an original observation, but Poitras bracingly updates it. With admirable patience and subtlety, she illustrates that even if targeted killings claimed relatively fewer innocents than they have, it is the continual disturbance of technical surveillance, the status of being a potential target indefinitely, and the prospect of quick and unbidden destruction that exact a psychic toll on all of the inhabitants of a nebulous battlespace.

In the ensuing multimedia installation Disposition Matrix, Poitras’s discourse shifts from the essentially visual to primarily documentary. Through illuminated slits in the wall, various surveillance-related items are on display. She starts with CIA Director George Tenet’s classified March 2002 request for the NSA to implement President Bush’s January 2002 directive to collect non-communications data from foreign computers and share it with the CIA, and proceeds to official definitions of clandestine collection and covert action and the parameters of NSA watchlisting. Punctuating this selective collation are, among other things, home video footage of air strike damage (including the collateral kind, here reflected in views of a wedding party site in Yemen before and after the notorious drone strike in 2012); a line drawing of a waterboard and other restraining apparatus; a series of photos of the NSA data center in Utah; and a Top Secret chart of NSA’s ominously quotidian “Corporate Forwarding Network.”

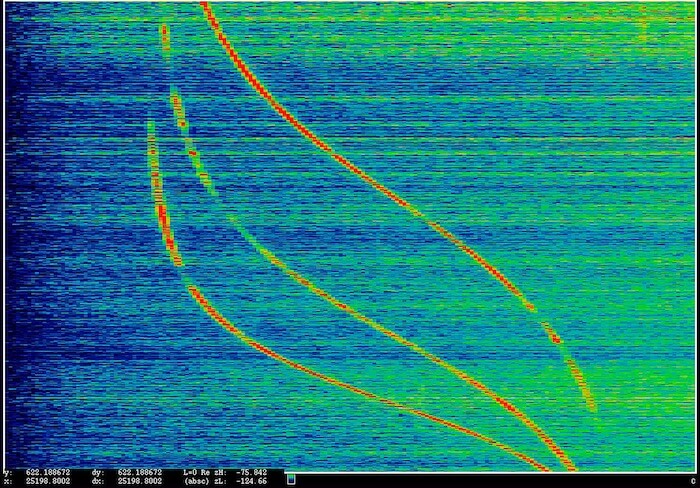

Laura Poitras (b. 1964), ANARCHIST: Data Feed with Doppler Tracks from a Satellite (Intercepted May 27, 2009), 2016. Pigmented inkjet print mounted on aluminum, 45 × 64 3/4 in. (114.3 × 164.5 cm). Courtesy the artist

There is also a confoundingly nuanced segment of testimony from retired NSA technical director William Binney—himself a whistleblower—on the NSA and CIA’s post-9/11 eradication of al-Qaeda targets: he defends it as surgical (that is, devoid of collateral damage) but he remains uneasy and distinguishes it from the broader and lengthier rendition program. Initial inscrutability—a Poitras hallmark—often compels and rewards lingering study. One offhandedly bland and opaque video shows wet concrete being poured and smoothed. It seems to allude broadly to destruction and the compulsion to rebuild, but also to the reality that what’s kept from view—the dead, the secrets, the means of collecting intelligence—won’t disappear. The time it takes to grapple with this expansive ambiguity makes it all the more sobering.

In a quite personal denouement, Poitras ratchets up her sardonicism. She proffers an unedited eight-minute-plus video she made on November 20, 2004, in Iraq, narrating that the existence of this footage prompted a long-classified US national security investigation of her that led to her being included on a watchlist and detained on suspicion of at least passively collaborating in an ambush in which an American soldier died. The filming occurred during a firefight, on a relatively remote rooftop with the Iraqi family that was hosting her. Gunfire is audible, but the area filmed does not take fire. The children joke that they are supposed to be scared, and one admonishes the other to “start shivering.” They express glee over not having to go to school. In sum, the film, while atmospherically telling, is operationally innocuous. That, of course, is Poitras’s point.

The show’s final piece, honing to a fine edge the theme of ubiquitous surveillance established by the inkjet prints of graphic computer readouts from the United Kingdom’s ANARCHIST signals interception program in the outer hall, is the video installation Last Seen. It consists of a scrolling list of monitored Wi-Fi signals, device by device. The data would not necessarily or predominantly be recorded on or from any battlefield, yet they are anything but innocuous. That too is her point, and, like myriad others registered in this somberly scintillating exhibition, it’s a point well made. Poitras may not offer answers, but she depicts the post 9/11 terrain in all its ugly complexity, and thorough situational awareness is essential to strategic progress.

You might also like