Literary Twitter Is People: The Faces Behind Your Favorite Literary Twitter Accounts

Insert all the praise emoji here

When I first signed up for Twitter, at the behest of my new employer, I was faced with a long list of verified accounts, some comedians, some celebrities, and a whole lot of brands. The New York Times, with a blue check next to it. The Paris Review. Alfred A. Knopf, its little borzoi about to leap across the screen. I clicked nearly every one of them. Would I like to follow Farrar, Straus & Giroux? Why yes I would. Thank you for asking, Twitter.

I found, as many other first time Twitter users eventually do, that a lot of these verified accounts, the impersonal and institutional especially, didn’t do a lot of talking on the platform. Instead it was, and still is, a lot of bleating: Did you know about this thing? Link. Check out our stuff! Link. Four people do something you won’t believe. Link. Enter for a chance to win! Link. “Deep quote.” Link. Snooze emoji. Link. Link. Link.

Everyone gets to make their own Twitter, which is part of the fun of it. (There’s also a complicated and anxious social math, with follows and follow backs and ratios of following to followers, but let’s just leave that in the dark basement of your (my) mind where it belongs.) This is to say that you get to choose who and what you see in your feed, and you get to change it as often as you like.

I have a nasty habit of reading (well, skimming) all of my timeline, every tweet, which means that I notice who talks and who merely announces. (Click this link!) And after that first flush of excitement—I have a direct connection to the inside workings of an institution I love!—faded, I unfollowed, one by one, most of those authorized accounts. But not all.

People love an institutional social media account that talks like a person. That’s why there are screenshots churning through Tumblr of DiGiorno and Taco Bell making cheesy jokes in real time, or of Denny’s gifs referencing the “when u mom com home and make the spagheti” meme. In particular, there’s a wealth of literary institutional Twitter accounts that talk like people. (Spoiler: They are people.) So charming are these voices that they’ve been regularly written up, by Newsweek, the Independent, BuzzFeed, the Takeaway, Metro, among others.

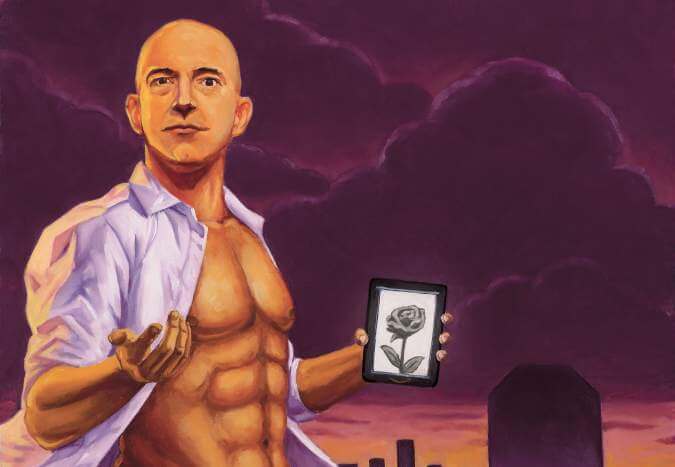

Kathryn Ratcliffe-Lee

“Authenticity is contagious,” says Molly Rose Quinn, the director of public programming at Housing Works Books, of successful social media presences. (She also tweets @HousingWorksBks.) “It’s viral. We have no publicity budget—independent publishers are in the same boat—we would not be alive without it.”

Don’t you just love it when people buy books? pic.twitter.com/Q2tupoih78

— Housing Works Books (@HousingWorksBks) December 30, 2015

“A personable social media presence is an incredibly important tool for building trust between the people who know the ins-and-outs of a particular industry and… well, everybody else,” says Emily Hughes, associate manager of content development and social media at Penguin Random House, aka the voice of @penguinrandom, the publisher’s official Twitter account. “The thing about book publishing, especially with the Big Five, is that it can be pretty opaque to outsiders, but social media (and Twitter in particular) has gone a long way towards punching some windows in that ivory tower.”

Kathryn Ratcliffe-Lee, a senior marketing associate at Harper Perennial (one of HarperCollins’s imprints) and the voice of @HarperPerennial in its many social media permutations, describes how she first learned how to run the account. Watching Erica Barmash—her predecessor at Perennial, now Bloomsbury Children’s marketing director—represent the imprint, Ratcliffe-Lee saw her “tweet about everything publishing or book-related.” She would openly talk about books outside of Harper Perennial’s list. “That just struck me as—why not? That’s obviously what consumers need. A consumer doesn’t need something limited to a specific brand that they’re not aware of it, especially in the publishing community where you can’t differentiate [among imprints] that way.” Barmash would also talk with people, not just repeat marketing messages. “That made me realize, oh, as a consumer or as a reader, as a person on the internet, I want to be able to provide what I would enjoy personally. I would enjoy talking to a brand if they were witty or informative, and also human. I want to be able to acknowledge that you are a person typing on the computer, versus oh maybe this is a scheduled tweet and I’m part of a bigger strategy here. It makes me feel like a person by acting like a person.”

It’s wild to read about what you’re doing as you’re doing it. pic.twitter.com/TBSVbUaqCW — Harper Perennial (@HarperPerennial) January 3, 2016

Julia Fleischaker, the director of marketing and publicity at Melville House, describes the publisher’s signature social media style. “Melville House was born out of a blog (MobyLives), so this kind of thing is in our DNA,” she says. The publishing house has “done a phenomenal job of bringing on knowledgeable and interesting people, and pretty much setting them loose on Twitter.”

Currently Liam O’Brien, Chad Felix, and, in the United Kingdom, Zeljka Marosevic handle social media duties. Alex Shephard, now the New Republic’s culture news editor, and Dustin Kurtz, a freelance writer and book marketer, also once held the reins, helping craft an institutional Twitter persona that is caustic, surreal, and sometimes really into Vines. In August 2014, Sheila Heti interviewed Shephard and Marosevic in the Believer about Melville House’s Twitter account. “We definitely have the sweariest account in publishing,” Shephard told Heti. “If someone I’m talking to has heard of Melville House, the first thing they mention is the Twitter feed.”

there are no “unread books” there are just rectangular reminders of your own cowardice

— Melville House (@melvillehouse) October 14, 2015

“Dustin was always better at it than I was,” says Sam MacLaughlin, who ran McNally Jackson’s Twitter account with Kurtz before going on to work at W.W. Norton. The bookstore’s Twitter account helped “remind people, people who are not necessarily in the store at that very moment, Hey, we exist, we have taste, we know what we’re talking about. Because it’s a bookstore, and a lot happens in a bookstore, it feels natural for it to tweet not just about books (good and, crucially, bad) but about all that stuff that can happen in a bookstore—the music playing, interactions with customers, insulting Amazon, etc. etc. etc. There’s a nice freedom there.”

I hope they find each other. pic.twitter.com/JtrqfN49Fo — McNally Jackson (@mcnallyjackson) April 25, 2015

“If McNally Jackson or Melville House had any success in finding a voice we could tolerate on [Twitter] as brands,” Kurtz says, “it was only because we were lucky enough to be talking about great books. A world different than trying to find something interesting to say about Cheetos every day. Actually never mind, now I’m imagining that and it sounds kind of fun.”

I look forward to wrapping up this year exactly like the last eight or whatever: tweeting solely to myself.

— Dustin Kurtz (@theunread) December 30, 2015

“I find it nightmarish to tweet ‘as myself,’” MacLaughlin says. “I have a protected account, basically never tweet, and when I do it’s usually just to tweet nonsense at Dustin. Much easier to hide, Oz-like, behind the curtain of an institution and pretend to be that place and uphold its standards than to pretend to be your actual self (or your idealized self, whatever).” “I appreciate being anonymous on the internet,” Ratcliffe-Lee echoes. “It gave me a little more freedom, creativity.” She took a screenshot of the Olive logo from the old Olive Reader blog. (The image is helpfully titled booklady.gif.) “I could play with the logos. I think it helps people recognize that image even if it’s unrelated to Harper Perennial.” The imagery gave the brand a face “rather than this magic perception of a person.”

All I do is win win win no matter what Got voting on my mind I can never get enough http://t.co/z7FLRa4dx1 pic.twitter.com/OVQqoFRCkm — Harper Perennial (@HarperPerennial) November 23, 2015

— Harper Perennial (@HarperPerennial) January 6, 2016

But other than anonymity, what readers see on the @HarperPerennial feed is pretty purely Ratcliffe-Lee. “I honestly don’t think too differently” on the official account, she says. “When I am tweeting as Harper Perennial it’s just me dashing off thoughts I have in my head, not terribly filtered for business reasons. Anything that’s mildly book related goes to Harper Perennial. Otherwise it goes to the personal account. And so when I am tweeting from Harper Perennial, I’m really tweeting as myself in some way.” Emily Hughes reflects on the differences between her personal and professional tweets. “Well, I swear a lot less on the work account. Like, a lot less. 110 percent less. I also don’t bring my personal politics to the Penguin Random House Twitter, at least not in a conscious way.”

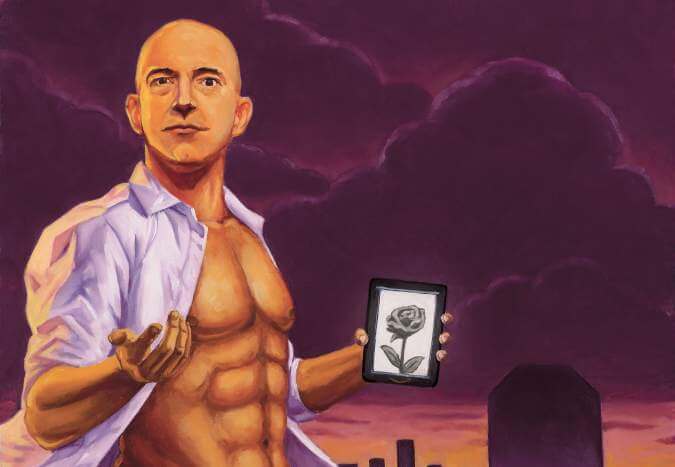

Emily Hughes

“At the same time,” she says, “in order to make any kind of an impact as a brand on Twitter, you have to let some personality shine through, so it can be a weird line to walk. You’re constantly making judgment calls—I shouldn’t make that joke, this could be worded better, that reference might be too obscure, etc. A lot of stuff ends up getting redirected to my personal account: risqué jokes, musings on goings-on in the industry, my own weird niche interests, rants about Donald Trump, stuff like that. On the plus side, when I think of a great book pun, I can now send it out to 800,000+ people instead of just emailing it to my dad.”

Charlotte’s Webinar #RuinANovelWithSocialMedia — Penguin Random House (@penguinrandom) September 24, 2015

When Sheila Heti asked Shephard if he had “an imaginary person that you’re being when you’re tweeting” as @MelvilleHouse, he answered: “I imagine that I am a bald, 50-year-old man who lives in Seattle and is worth roughly $30 billion. Or, if there are enough candles and chalk in the office, I summon the actual spirit of Herman Melville and let him tweet through me.”

The relative anonymity of the people who write all these tweets obscures the IRL, personal relationships that help shape their digital, professional conversations. When @PenguinRandom and @MelvilleHouse got in a Twitter fight in October 2015, it got its own Twitter moment as well as coverage in four different media outlets. It even made a Newsweek list of the best fights of 2015. But what many of these stories don’t acknowledge, and likely don’t even know, is that @PenguinRandom’s Emily Hughes, and @MelvilleHouse’s Liam O’Brien… are dating. They live together!

“lol what’s work” — @melvillehouse

— Penguin Random House (@penguinrandom) October 16, 2015

“Professionally, we met when we worked together at another publishing house, and I deeply respect him as a fellow brand tweeter and the person who coined #brandter,” Hughes says of O’Brien. “Personally, could you remind him to pick up some cat food on his way home tonight?”

“We hear all the time how nice it is to see a corporate account with personality, and I think that’s what we saw with the ‘twitter fight’ between Melville House and PRH, and the one with Olive—aka Harper Perennial—before that,” Melville House’s Fleischaker says. “It’s refreshing to see companies not take themselves too seriously, and show some personality. As for Liam and Emily, what happens on Twitter stays on Twitter.”

@HarperPerennial check this dope selfie pic.twitter.com/uMNl2ymIrX — Melville House (@melvillehouse) August 17, 2015

@melvillehouse Updated it for you. pic.twitter.com/YrpB7cadGo

— Harper Perennial (@HarperPerennial) August 17, 2015

“I want to develop relationships with the voices that I enjoy and have a direct impact,” Ratcliffe-Lee says, reflecting on why she does—or doesn’t—interact with other brands. When she is interacting with another institutional Twitter account, it’s usually because she knows or likes the voice that animates it. Otherwise, “a conversation with another brand might not be worth my while.”

@penguinrandom @melvillehouse @Quinnae_Moon this is like watching my library fight itself or like watching The Pagemaster — Bryant Francisclaus (@RBryant2012) October 16, 2015

Ultimately these literary institutions are on Twitter because that’s where people already are. That’s the most crucial work they do, interacting with their readers and customers. Engaging in, to use O’Brien’s phrase, “brandter,” while highly diverting for both the account’s writers and readers, is secondary to this role.

“I do a lot of talking to readers and talking to customers on Tumblr,” Housing Works’s Quinn says. “Sometimes I’ll tweet about a book and I see someone tweet—I’m coming by to get that. That’s so cool.”

“One of the best examples of how Twitter has allowed us to engage with our followers was when we crashed the Torture Report,” Fleischaker says. “We were pretty much live tweeting our all nighters, and, in true fits of kindness, Twitter followers sent us cookies and beer in support. It was amazing to read the tweets, and see how many people were rooting for us to get this thing done. It made Twitter feel like a wonderful, cozy, mutually supportive community.”

“The rich tapestry of humanity you encounter in the mentions on a given day is a treat,” Hughes says. “A lot of people want to pitch us their books (please don’t do this—even if we could accept unagented submissions, I am definitely not the person you want evaluating your manuscript). Sometimes people point out typos, or alert us to instances of piracy, or ask us to help them remember a particular book title or author name (not to brag, but my batting average on that last one is pretty damn good). We also get tagged in people’s excited tweets about book hauls and galley mailings, which is weirdly gratifying. Hashtag games are my favorite, though—it’s almost unreasonably rewarding to send a bunch of groan-worthy bits of wordplay out into the void and have the void come back and out-pun you.”

“They gave me the account and don’t have any expectations of me,” Ratcliffe-Lee says, reflecting a laissez faire attitude many of publishing’s higher ups feel about social media. Whether the free reign that’s been given to these (incredibly successful) accounts has been a matter of employer apathy or trust in their employees, the policy has for the most part worked. (While more formal Twitter accounts slip up all the time.) But for all the goofing around—with readers and with each other—advocating for books online is serious, important work. “Being able to represent employees, authors, it’s really an honor,” Ratcliffe-Lee says. “It’s high pressure, but it’s an honor. I’m really grateful that I found a workplace that can appreciate the weirdness and know that it’s good.”

She laughs as we finish up our conversation. “I clearly enjoy this,” she says. “Let’s redact everything I said.”

You might also like