Street Smart: Goodbye Cars, Hello Future

Sam Schwartz meets me outside of the Barclays Center in the open air plaza he helped engineer. A native Brooklynite, he takes special pride in the arena. “This is where Walter O’Malley wanted to put the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1950s. He broke my heart when he moved them to Los Angeles.”

One of the country’s leading transportation experts, Schwartz spent two decades as New York City’s Traffic Commissioner and its Department of Transportation’s Chief Engineer and, since 1995, running the world-renowned engineering firm, Sam Schwartz Engineering. He’s also known as “Gridlock Sam”—after all, he helped invent the term. His new book, Street Smart: The Rise of Cities and the Fall of Cars, is a kind of manifesto in praise of urban spaces and multimodal transportation (by foot, by bike, by bus, by train, even—sometimes—by car), and in many ways the Barclays Center embodies his argument.

“This is the epicenter of Brooklyn,” Schwartz says, gesturing towards the intersection of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. “That’s the challenge. We had make sure that this didn’t turn into a traffic disaster.”

“The real key was to get fewer people to come by car and still have record sales,” he says. “It’s always a double-edged sword.”

“Some of the changes—terminating 4th Avenue going northbound—were about making it easier for pedestrians to get across different streets, making the intersection a little simpler for traffic.” But he also had to find a way to convince people who normally drove to Nets or Islanders games to go without cars. They targeted hard-core drivers in their focus groups. “If we offered them free meals, free subway passes—it meant very little to them. The only thing that really resonated was that they didn’t know how to get here by train. It was information that was so powerful.”

“I take it you are a millennial?” he asks. I assent. Much of his book has to do with millennials, or rather the new priorities and habits that shape many of their (our) lives: First, by choosing to live in denser, more walkable areas and, second, by choosing to drive less—for the first time since the invention of the car—than the preceding generation. Much of this has to do with information. “Your generation has unlocked the mysteries of transit just with a smart phone. I can put you down in any developed city and you can find a train, a bus.” He pauses. “But this was before the smart phone became so ubiquitous,” he says, returning to the Barclays Center focus groups. Before their phones demystified it for them, the drivers of the New York metropolitan area how to be taught how to use their public transportation systems. “We blanketed all the LIRR cars with flyers. LIRR and MTA did a great job,” he says. “And we always said publicly that traffic would be a nightmare. First, because it really is hard to drive around here. We also wanted to discourage people from even thinking of driving. It really worked.”

The Barclays Center, of any arena or sports facility in the United States, has the lowest percent of visitors coming by car. “We’re down to 25 percent,” Schwartz says. Of the 600-car capacity parking lot that eventually was built (itself much smaller than the suburban facilities that have to accommodate thousands of vehicles), it barely fills up halfway. “So much of the United States is about providing one parking spot for your home and one parking spot at work for each person, and it’s crazy. We’ve overpopulated our cities with vast parking areas. In Atlanta you’ll see building, parking garage, building, parking garage, building, parking garage.”

It’s a grim vision. “It wasn’t the right thing for Brooklyn, especially this part. I went to school in this part of Brooklyn.” He points to a distant spire of Brooklyn Tech, his alma mater, visible just over the roof of the Atlantic Mall. “I know this area very well.”

The beginnings of car culture

Schwartz grew up in Brownsville and then Bensonhurst. Though he left the borough for a stint at the University of Pennsylvania, where he got his Masters of Science in Civil Engineering, he came back to live and work and raise a family. He met his wife in Prospect Park. They bought a house in Flatbush. His kids went to public schools. “We’re firm believers in the greatness of Brooklyn,” he says. When he did decide to move to Manhattan for the first time a few years ago, it was in part because “I felt Brooklyn was on the right track. I didn’t feel like I was abandoning it.”

His memories of Bensonhurst in the 1950s tinge rosy, if they aren’t exactly idyllic. “There was still a taste of what Brooklyn was like prior to the car. Unfortunately in that neighborhood the playgrounds were where the gangs hung out. In the street we played football; in the street we played stickball; we played such a variety of games. I organized the 83rd Street Olympics—jumping and races and everything. We all knew to yell ‘Car!’ I don’t recall a kid every getting hit by a car. Somehow it always got out of the way.”

Cars are often—though not always—the villain in Street Smart. Or rather, the book condemns the allocation of resources to cars at the expense of so many other modes of travel. Before the advent of the automobile, roads (especially urban ones) were used for recreation and commerce as well as transportation. “Horse-drawn carts trying to negotiate a road like Bedford Avenue would have had to dodge pedestrians who filled the street,” Schwartz writes. “Peddlers and other tradesmen were as entitled to the street as wagons. Children played in the middle of those roads, and adults met one another there.” With cars came the battle over right-of-way, a concerted push by auto makers and dealers, tire and rubber companies, insurers, and auto clubs (including a young AAA) to ensure that roads were for drivers, exclusively. That meant that setting aside valuable curbside real estate for parked cars and tearing up thousands of miles of streetcar tracks in the center of roads.

“I really bemoan the fact that we gave up our streetcars,” Schwartz says. “Where we’re sitting right now,” he gestures from beneath the awning of the Barclays Center, “I have pictures of Flatbush and Atlantic filled with streetcars. We stupidly gave them up.”

Streetcars, which were first built by power companies looking for a reliable customer for their energy, were often not well run. But by 1905 thirty-thousand miles of electric street railway ran through American cities, and streetcars represented an important and valuable public utility. In a plot that Schwartz likens to Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, General Motors, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil, and other large auto-related corporations set up two shell streetcar companies that went on to buy over 100 real streetcar companies in over 45 cities throughout the 1930s and 40s. These purchases were approved on the pretense that the new owners would continue to operate the existing streetcar systems. Instead, the companies were shuttered, the tracks ripped up.

Unobstructed, cars shaped the century that followed: striping the country with asphalt, carving up city neighborhoods and downtown areas with expressways, ballooning buildings with vast parking lots, and spilling millions of white families into suburban cul-de-sacs. For Schwartz, the battle against a car-only system of transportation is personal. He blames cars for the loss of many of his boyhood friends, who all moved away from Bensonhurst to more car-friendly areas. But the tide is shifting. “I find that most places that I go to, there’s a lot of interest in cities returning to what their nature was, except for that 100-year period of car domination,” Schwartz says.

“We are seeing lots of cities that weren’t on our radar,” he says of his work at Sam Schwartz Engineering. “We just got hired by Boise, Idaho. We’re in South Carolina. Atlanta is rethinking itself. Many of the smaller cities in Pennsylvania. In Grand Rapids, Michigan,” he says, rattling off names. “Everyone wants millennials now. Everyone wants a tech center. It’s just not possible that every city is going to have a big tech center.” He tells a story about Grand Rapids, where a tech company was being shown around a warehouse the city thought would be a perfect location for their offices. It had all the parking in the world, Schwartz recalls, but when the tech company saw the site, they asked: Where are the bike lanes? Where do we park our bikes? “The suburbs, they are much harder to sell,” Schwartz says. Younger people—millennials if you must—are electing to move, in greater numbers than ever, to walkable places with multiple forms of transportation. He’s gotten hate mail from suburbanites for his opinions. “I’m not saying that I want to change your lifestyle one bit,” he goes on. If you want to live in a car-centric suburb, fine. “But if you want to keep your children,” he says, “you should think about the form of your city and community.”

“I do have a car,” Schwartz admits. “It’s really a company car.” The subway, little surprise, is his primary mode of transportation. When he lived in Soho, he often rode a Citibike to work. (Since moving to the Upper West Side, where Citibike has yet to arrive, his biking—Schwartz laments—has fallen by the wayside.) “Walking, I do seven or eight thousand steps a day.” He tracks the number with his smartphone. The health and social benefits of active transportation—walking, biking—are much lauded in Street Smart. “Walking makes us more hopeful,” he writes. Travelers interact with their environment and community more and better when they aren’t inside a giant metal box on wheels.

“Once I did 20,000 steps in one day,” Schwartz says, smiling. That’s about five miles. “I did that in Barcelona.” In his work for Sam Schwartz Engineering, he’s traveled to places as near as, say, Queens and as far as the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea. He examines the transportation systems he has most admired in Street Smart: from the Catalonian city to Salt Lake, Zurich to Vancouver. “Barcelona is really one of the best cities. They really respect pedestrians.” As of 2012, only 26 percent of all travel in Barcelona was by car or motorbike. “They measure things differently,” Schwartz explains. “The Traffic Department changed its name to the Department of Mobility.” Barcelona’s broader focus, not just on motor traffic but on all travelers, meant that they started collecting data that cities really never had before. “For years, all we ever measured in New York City, and in most cities around the world, was traffic. The number of cars.”

Barcelona’s success lies in part because of this data collection but also in the practical measures they took to make travel by car generally slower and more difficult. This meant lowering the speed limit, converting streets into pedestrian walkways, and narrowing lanes. These traffic calming measures mean that the number of pedestrian deaths in traffic collisions is, per capita, about a third of New York’s.

Schwartz is getting ready for the Pope’s arrival. “I’m lucky I had time today,” he says. His firm is working in DC, in Philadelphia, in New York. “A lot of roads are going to be closed.” He’s most worried about the public mass in Philadelphia (which ended up taking place without a major hitch)—most of the travelers would be coming from the northeast. They’d have to park in New Jersey and walk over the Benjamin Franklin Bridge into the city. He had done the walk himself three weeks before. “I’m pretty healthy, but 53 percent of the people who responded saying they were going to the mass are senior citizens. A lot of those people will have walkers. They are going to see the Pope no matter how they struggle.” He’s less worried about the walk there—which would take place in daylight—than the walk back.

In New York, Schwartz worries about the Pope’s spontaneous acts of socialization. “He’s a person of the people,” he says. “Just about everybody is expecting him to get out at some point and just walk around.” Schwartz has been in his share of motorcades. “In the late 1980s, I was in the Gorbachev motorcade as Traffic Commissioner. I was in the sixth car and he was in the tenth car. All of a sudden we noticed there were no cars behind us. Gorbachev had gotten out and walked into the middle of the throngs of people at Times Square.” Though it makes his job more difficult, Schwartz seems to admire this quality about both men. They are pedestrians too.

“We have a lot of other projects that we’re working on,” Schwartz says, beyond the Pope. “We’re working with the Port Authority to figure out what to do with the bus terminal. We’re working for Hudson Yards, trying to solve some of the logistic problems. We’re doing a test for closing 33rd Street near Madison Square Garden, the same thing for a portion of 32nd Street.”

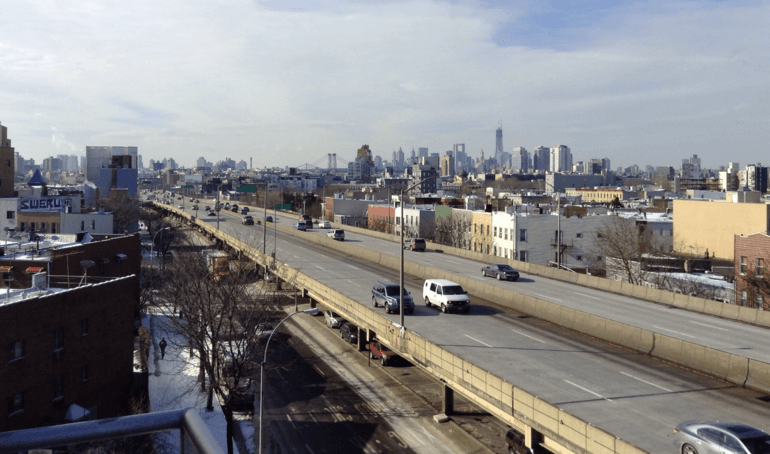

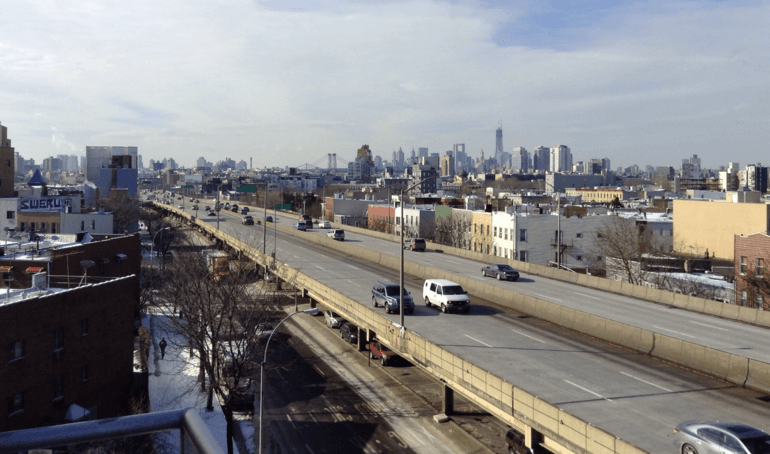

For most of us, living in a city (or any physical environment) means being shaped by it. Seemingly fixed geographical realities determine how long it takes us to get from home to work to school to a shopping district, and how pleasant that journey is. You cannot control whether a street is quiet and tree-lined, just as you can’t help the shadow of the BQE or the difficulty of crossing Linden Boulevard’s ten terrifying lanes. You can choose, if you have the money and there is the available housing stock, whether or not to live in a place, but you can’t—as an individual—change the place itself. Of course people do affect change, often and most effectively when they work together. Activist Jane Jacobs, after all, stopped the near limitless power of Robert Moses in its tracks—a feat not even FDR could accomplish. (The infamous city planner had tried to build a raised highway down 5th Avenue, demolishing Washington Square Park in its path.) Rich people, too, do a great deal of shaping, whether as builders or as obstructions to building. But for everyone else, cities appear for the most part immutable. Tenants change, so do store fronts, but the streets and blocks they sit on look like forever. The transportation realities of living in places like Red Hook or East New York feel, likewise, everlasting.

It’s intoxicating to look at a city with urban planner’s eyes. Anyone who has built a place with blocks or pixels has felt something similar. Buildings can be lifted up and set down again, roads pulled wide or narrow, bridges raised, tunnels dug. If you don’t like something, you can change it. Demolish, build, rinse, repeat. Few individuals have had the carte blanche to shape cities in this way, a kind of power for everyone else only imagined in play. Robert Moses was one, Janette Sadik-Khan—commissioner of New York City’s Department of Transportation from 2007-2013—is arguably another. (You can thank her for most bike lanes in New York City, among other things.) The enterprise of urban planning, however, is one that focuses on the big picture. You begin to see things, places, as malleable.

When he talks about his future projects, Schwartz helps foster this image of a city that can, and will, change. “I am involved in the Brooklyn/Queens street car,” Schwartz says. “I can’t say too much about it but it’s very promising. The Brooklyn/Queens waterfront is bursting with population, with job opportunities, with a lot of low income housing. It’s almost the perfect location for a street car.” Street cars, again in Brooklyn! Schwartz describes a system with no overhead wires. (“An installation and maintenance nightmare,” he says.) “Batteries have gotten so powerful that you can go on a single charge for 18 hours.” Schwartz had built a similar system in Aruba. “It’s a lot of fun to ride,” he said. It’s easy to imagine, once you get the hang of it—how quickly a line of track can be laid down in the map of your mind.

Schwartz mentions the September collapse of a section of a G train tunnel wall. “That’s the problem with our subway system,” he says, no money for maintenance. “Today there was a LIRR derailment. Everyday there is a signal failure in the system. We need to come up with a steady stream of revenue.” The basic cost of MTA system maintenance, Schwartz estimates, is $20-30 billion every year. “Bridges just to our north were all built with tolls, and the tolls go to maintain those bridges.” He’s talking about the Whitestone, the Triborough, the Throgs Neck. But the bridges directly east of the borough—the Williamsburg, the Manhattan, and the Brooklyn—are free, and so without a regular source of maintenance money. Thankfully they were built strong, Schwartz says. “They should have collapsed because of how we have used them.” Schwartz inherited responsibility for the bridges when a scandal cleared out the city’s Department of Transportation in 1986. He suddenly found himself the acting commissioner as well as chief engineer of the whole system. He also found bridges perilously close to collapse.

“The Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges were two of the scariest bridges,” he says. He describes in Street Smart a visit to the Manhattan that found nearly half of the steel in the cables holding up the bridge had rusted away. “Mathematically we could have had a situation where you had for whatever reason loads of trucks lined up on the Manhattan Bridge and you had a subway trains that were stuck one behind the other, then it would have collapsed.” He ordered train traffic rerouted and shut down the upper deck of the auto road. The Williamsburg Bridge was worse—he had to close it entirely. “We had to spend in excess of $3 billion repairing those bridges because we don’t have a dedicated revenue stream,” he says. “And even with all that, people still call them free bridges. That money came out of everyone’s pocket. We stole from schools and from homeless services and health and hospitals, because had we maintained it properly we wouldn’t have spent all that money. It’s a fraction of the money.”

This is where Schwartz starts talking about congestion pricing. In his book, Schwartz describes how the man who coined the term—Columbia economics professor William S. Vickrey—conceptualized the idea. Vickrey “talked about how a car, especially a driver-only car, was the least efficient way of using space, which was the most precious resource in Manhattan. And that we should treat it the same as any other precious resource: put a high price on it.” Schwartz tried to enact something along those lines as early as 1980, by writing a traffic regulation that forced driver-only cars to access Manhattan via a tolled bridge or tunnel. No free entry. He was sued by AAA and the city’s garage operators. Ultimately the courts decided that only state authorities, not the city, could decide to distinguish between driver-only and multi-passenger cars. Schwartz tried a variation on congestion pricing again in 1987 and faced a similar response. In February 2015, however, he introduced Move NY, a plan he has worked on for years pro bono. Bill Keller in the New York Times called it “a Brooklyn boy’s gift to his city.” The basic idea is to cut tolls where they already exist and add them where they don’t. The outrageous $16 cash (or $11 with EZPass) toll to Staten Island would be cut almost in half, and the Brooklyn Bridge could cost around $5 to cross. Schwartz’s plan would also introduce peak and off-peak pricing for tolls as well as surcharges for cabs and hired cars traveling in Manhattan south of 96th Street. The idea with all of these measures is to create additional revenue streams for public transit and for roads, and to “make sane” a bridge system that punishes people who travel between outer boroughs but subsidizes travels for its most popular crossings. When he hears I would soon be traveling to the Adirondacks, Schwartz first gives me directions on how best to drive there and then remarks, “My plan would slash $5 dollars off your trip.”

“At the moment we have about 50 elected officials who have signed on. We’re hoping to get the governor, the mayor—the battles are daily.” He’s glad to see that more and more people are using mass transit. The more people rely on it, the more people will advocate for it. “Something’s got to give,” Schwartz says. “Sadly it often requires a calamity.” He witnessed a few during his tenure working for the city—and not just a suspension bridge hanging by too few threads. He recalls when, in 1973, a portion of the West Side Highway collapsed. A Brooklyn dentist died. “We had lanes closed on the BQE because pieces were falling in Sunset Park and the Gowanus section,” he continues. “We had two pedestrian bridges that collapsed, fell to the ground. Cables snapped on the Brooklyn Bridge killing a Japanese tourist.” It very well may happen again.

“We know that one of the two tunnels that connect New York to New Jersey is likely to fail within the next ten years. In Brooklyn, the BQE in Brooklyn Heights probably doesn’t have a life more than ten years, and that’s a lifeline for truckers through the region. The East River bridges are in good shape, but we’re going to see more and more transit delays, transit failures,” Schwartz says. “The system is getting overloaded. We’re going to pay for it one way or another.”

This is the flip-side of urban planning euphoria. Along with the imaginative freedom, there’s also the crippling realities: of maintenance, of money, of politics, of human cost in lost hours and in life. Bridges, tunnels, roads, trains have to be safe. They should also be efficient. And while their construction may be glamorous and well-funded, their upkeep is rarely either. This ultimately is the great strength of Schwartz’s vision in his work and in his book. He is acutely attuned to the importance of the unglamorous, having already grappled with incredible cost of a weakened infrastructure. This is what grounds his visions for a future New York—a city that can live up to Street Smart’s name—Schwartz does the math. All of a sudden the city opens up again, at least your idea of it, a shifting puzzle to pry open and make new.

I asked him if he had unlimited powers and budget—Robert Moses-like sway or the “rosebud” cheat in SimCity—how he would change New York. Practical, Schwartz starts with the basics. “I would rebuild the infrastructure that needs rebuilding.” Then he elaborates. “I’d start using a GPS-type system to charge people for the amount of time that they use roads and cars,” he says. “I’d make the Belt Parkway into an expressway to take a lot of trucks off of city streets. It’s crazy that we don’t allow trucks on highways but we put trucks on city streets.”

Then he gets to trains. “I would build subways that would go out to Staten Island,” he says, citing the tunnel from Brooklyn that was begun in the 1920s but never completed. “I would complete some of the unused rail lines in Queens. I would bring back street cars. I would build the Triborough R/X, which is the subway line that would go along unused rail lines in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx. I would recognize that there is a lot of gravity between the boroughs, not just going into Manhattan,” he says. “I would extend the subways lines further into the Mill Basin area, into Canarsie, in quite a few places.” Imagine what it would look like, subways snaking out beyond their last stop and new connections webbing the boroughs. A kind of city where a Brooklyn/Queens romance doesn’t count as long distance, where you can finally try that restaurant you’ve always meant to go to because now there is a train that will take you there. A city where you finally, finally, go to the Bronx.

“I would build the first bridges to Manhattan since 1909,” he says. “I’d build bike/pedestrian bridges, one that goes from somewhere in the Red Hook area to Governor’s Island to Lower Manhattan. I’d build another bike/pedestrian bridge that goes from Greenpoint to Hunter’s Point, to the Cornell campus on Roosevelt Island, to midtown Manhattan. I’d build a third to Hoboken and Jersey City.” A city festooned with bridges, a city whose rivers aren’t just a concept you consider from a train window.

A smart city takes advantage of private transportation services like Uber and Lyft and Via “while at the same time realizes there’s a sweet spot. There is a point where too much of any one of these services or all these services will bring us closer and closer to gridlock. And we’ll have less services as a result. There’s also the cascading effect of stealing people from transit, who are thinking transit is less attractive. And that’s the real risk. There’s also the real risk that lower income people will not see the benefits if we only let the private sector dictate these services through market forces. Downtown Brooklyn will be well-served but Brownsville will not be well-served,” he says. “A smart city lets the entrepreneurs in, while protecting businesses like yellow taxis and others, and having smart controls that are based on the very best information. For example, in midtown Manhattan travel speeds should never dip below eight miles an hour, so that if they do, they begin to raise the fees. In a smart city, using 5th Avenue will cost more than using 1st Avenue. Using Atlantic Avenue will cost more than using Avenue U. In a smart city gasoline tax is kind of dumb. You’d be charging people for what they use, treating space as a commodity.”

“In many ways it is New York’s most precious commodity,” he says. “We can’t build more of it. It should be priced accordingly.”

“Now is the time to plan for 2030,” Schwartz says. “We were behind the eight-ball when it came to Uber. We just didn’t see it coming. What’s coming is Google has invested in Uber. I call those cars Goobers.” He smiles broadly, laughing a little. The same joke—emblematic of Schwartz’s goofy charm—is in the book. “In 2030, sitting here, we’re going to see a lot of egg-shaped cars that have almost no protection in them because they won’t need any protection. They’ll be so safe, they won’t hit anything and nothing will hit them.” This is maybe harder to picture—a street full of eggs—but go with it. I didn’t expect the non-hovering wheelie boards either. “You’ll end up seeing the streets jammed with all these eggs traveling around,” Shwartz says. “We could be seeing our subway system suddenly deteriorating as a result, and those eggs won’t be available to the people of Brownsville or East New York and other lower income parts of the city.” Schwartz wants the wealthy to buy into public transit because it’s a resource that can be shared across the city. While cars, whether or not they have a driver, demand the upkeep of roads, well-maintained streets do little good to families who can’t afford a vehicle. “There’s a real risk,” he says, of the driverless car’s impact on mass transit. “A smart city would start preparing now for autonomous vehicles.”

Schwartz vision combines elements that feel at once sensible—letting trucks onto the city’s parkways is as simple as changing the signs—and fantastic—all those bridges, all those trains. But the trains and bridges we have today were built by someone at some point who decided yes, we can do this and yes, we will. If Schwartz’s many decades in New York City have helped him see how difficult it can be to enact change, it’s also shown him what can be accomplished. “John Lindsay was so far ahead of his time,” Schwartz says of the first mayor he worked under. “I was so excited, I mean I was beyond excited.” Though he was an entry-level engineer just out of the Civil Service exam, Schwartz found the projects he worked on thrilling. “From the red zone banning cars from midtown Manhattan, to tolls on the East and Harlem River bridges, to the Time Square plazas that we have today,” the Lindsay administration wanted to limit cars and prioritize pedestrians. Lindsay’s proposal’s faced intense opposition: the red zone and the bridge tolls were never enacted, and Time Square’s plaza only recently opened under Janette Sadik-Khan. But the mayor was able to accomplish some things. “Fulton Street, just a few blocks away,” Schwartz says, “was done during the John Lindsay era.” The bus-only street was one of the first of its kind in the nation.

It’s clear, from his conversation and from his book, that Schwartz is in it for the long haul. New York could be better. It should be.

“When New York City does something, like in Times Square, its front page news in Paris, and London, and New Delhi,” Schwartz says. “And so doing something in New York, it’s a bigger platform… New York creates itself, its people. It’s electric.”

You might also like