One Fish, Two Fish: Inside the Fascinating World of Greenpoint’s Acme Smoked Fish

Acme Smoked Fish in Greenpoint

all photos by Alex Srp

Richard Schiff hands me a blue plastic apron with sleeves, a blue hairnet, and a pair of blue disposable shoe covers. When I’m ready, I follow him through the office and onto the factory floor. Out here, the temperature is a little cooler and there are signs on the walls in English, Polish, and Spanish, listing rules about workplace safety.

In front of us, a line of about 130 people are queued for a chance to buy smoked seafood: hip twenty-somethings, parents with kids, little old ladies, and everyone in between. “Today is very unusual,” explains Schiff. “There’s a few times a year when we have a line that extends out the door and down the block a little bit, which are before Yom Kippur, Christmas, New Year’s, Thanksgiving—major holidays.”

Schiff is the general manager at Acme Smoked Fish in Greenpoint, and this particular Friday happens to be right before Yom Kippur. I watch a bearded man carry out two shopping bags heavy with fish, and everyone in the line patiently moves forward—Fish Fridays are the only time that ACME sells their products directly to the public at wholesale prices.

“We have the widest selection of smoked fish available anywhere, certainly in the country,” says Schiff proudly as we veer a left through two double doors. “I would even say anywhere in the world on Fish Fridays—pretty much anything we make is available for sale, whether it’s a different variety of cold smoked salmon like pastrami, gravlax, or lemon pepper or different cuts, like our Royal Cut.”

We step into a wide corridor with a long industrial sink against the wall, and the temperature drops again. Up ahead, I see an employee in a tan jacket, white apron and hairnet, and rubber boots pushing an empty metal rack. “At this plant, we have about 150 workers in total, including our factory workers and administration, drivers, sales people,” Schiff explains.

In 1905, however, it was just a company of one: Harry Brownstein would drive a horse-drawn wagon to local smokehouses to purchase the smoked fish himself and then distribute it to appetizing stores. As the business grew, Brownstein’s three children joined their father to help him manage it—as would their own children a generation later.

By the 1950s, the family was ready to open a plant on Gem Street in Greenpoint, in a small rented space then-owned by a funeral parlor. Brownstein decided to call it “Acme” not only because of the word’s definition (“the point at which… something is best, perfect, or most successful”) but also because it would be listed first in the Yellow Pages.

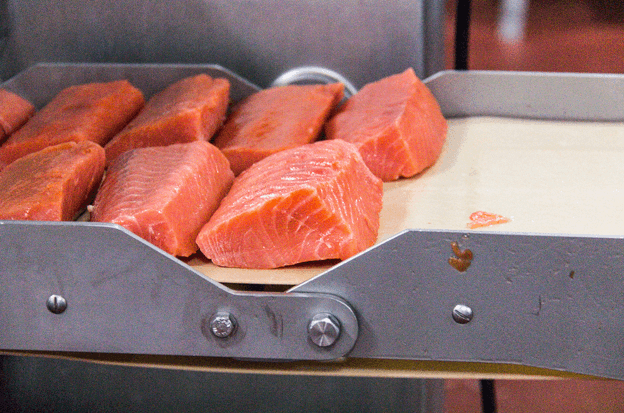

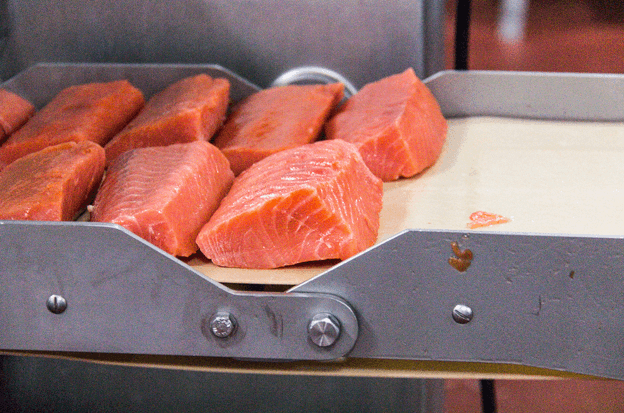

When an opportunity arose to expand into the adjacent Williamsburg Steel building, the family took it and, today, the factory boasts 65,000 square feet of space. “Out of this plant,” says Schiff, “on cold-smoked salmon, we’re able to do about 20,000 pounds a day.

“In whitefish, in the hot smoke area,” he adds, “we can do a similar daily number of about 15,000 pounds daily.” We start our tour in a vast room where, at one table, a group of workers is cutting whole salmon. Nearby, at another table, two workers are coating fillets in spices. A third group is busy defrosting fish that have arrived packed in boxes. Surprisingly, it’s neither loud inside nor does it smell overwhelmingly of fish.

“There’s a lot of different critical control factors for food, like temperature, bacteria, the supply chain,” Schiff says. “Food safety comes before everything because without it, we have nothing.” He pulls open a few sliding doors to some of the smoking rooms—I see racks upon racks of fish hung tail-side up—and talks excitedly about how everything is made. “I’ve been here since 1992,” Schiff says, “and I’ve done pretty much every job here.”

He started when he was still in college (studying graphic design) by selling fish to the public on Fish Fridays. “That was when, occasionally, someone would come in and want to buy something,” he remembers. “That was all me, and maybe fifty people would come in spread out throughout the day.”After graduation, the company offered him a job.

Years later, Schiff has done everything from skinning and filleting fish to driving trucks to designing the Acme packaging. He walks the floor seemingly knowing every tool, every machine, and every square foot of the facility. (Since everyone wears name tags, I can’t tell if he really knows every worker’s name.)

“In the early 90s, probably 85 percent of the customer base was Polish immigrants who lived in the neighborhood and they would walk here,” Schiff says. “Over time, you had your sort-of pioneers of the neighborhood, and they were the first ones.

“Now not only has our customer base changed, but our workforce in the factory has changed a lot,” he adds. Schiff has also noticed that the workers will mostly carpool from Queens. “I can’t tell you how many times that I get here at five o’clock in the morning,” he says, “and there is not a spot to park because they’re not walking anymore.”

We stop by a table where a machine the size of a carry-on suitcase ever-so-slowly slices a salmon fillet. A female worker in her late-forties takes the pieces and arranges them on a small gold-colored board. Schiff gingerly takes one and holds it up to the light: It’s translucent. This, he explains, is as fine a cut as a machine can make to mimic the human touch. The taste will be “silky, buttery, and smooth.”

Has America’s appetite for smoked fish changed? I ask him. “Fortunately for us, I think it’s increased quite a bit,” says Schiff. “When I started here and certainly before that, smoked salmon was a way more ethnic food in New York and certainly the country. It was a very ‘Jewish item.’ Now, there’s been a lot of attention paid to it.”

We move on through the factory, pausing to watch how smoked whitefish salad is made (a combined human and machine effort), until we end up in the packaging room. Here, a long counter has been set up with retail portions of everything Acme has to offer. Fifteen employees take customer order from the line.

“I’ve been here more than any other stage of growth in my life,” says Schiff, looking around the room. “This is like my second family.” He points out one of the Caslow brothers—a grandson of founder Harry Brownstein—who briefly comes into the packaging room to check on something by the register. I imagine that, by now, fish—specifically, salmon, whitefish, sable, and herring—must be swimming in his veins.

You might also like