With Fat Suits and Psychics, a Photographer Acts Out His Own Sad Fates

After photographer Phil Toledano’s parents died several years ago, he found himself wracked with anxiety about all the horrible, unexpected turns his life could possibly take. “I’d see a little old lady on the street and think about how I was going to get old and die,” Toledano says.

It’s an experience to which many can likely relate. But instead of seeking therapy (or a Xanax prescription), Toledano decided to channel these obsessive fears into a photography project. For the next three years, he would test his DNA and visit psychics, then dramatize and photograph the future scenarios he dreaded the most.

In The Many Sad Fates of Mr. Toledano, a short documentary by director Joshua Seftel (War, Inc.), we watch the photographer live out his worst nightmares: suicide, stroke, morbid obesity, violent death. Then there are less grisly but still bleak fates: Toledano as an old man paying for a prostitute, as a stymied aging office mole, as a vain rich guy with too much plastic surgery. Toledano’s chameleonic transformations, through makeup, costumes, and prosthetics, are reminiscent of the work of artist Cindy Sherman, if Cindy Sherman were a morbid middle-aged man.

Toledano’s dramatized fears are both very specific to him (not everyone is terrified of becoming a biker guy with a mullet) and universal (almost everyone is afraid of dying). But despite how widespread they are, it’s rare that someone is as willing to publicly confront these neuroses as Toledano is, which is what makes this film so successful. It’s a bit like an artistic interpretation of the principles of exposure therapy, which helps people overcome phobias by gradually exposing them to the feared stimuli. Turning this type of therapy into theater proves to be darkly funny and, somehow, strangely therapeutic for both Toledano and his viewers. Because despite all of Toledano’s professed anxiety, doing this project was a brave move–imagine if Scrooge in A Christmas Carol had decided to spend three years hanging out with the depressing Ghost of Christmas Future instead of trying to get away from him. The photographs have also been compiled into a book, Maybe.

We sat down with Toledano and Seftel to talk about why dressing up as depressing future versions of oneself can be liberating.

What was the saddest of all the sad fates you dramatized? Is there one that you really, really hope doesn’t happen?

Phil Toledano: This may seem odd, but what I found scariest were the office worker scenarios. Because if I’m in an office in my mid-50s, that means I’ve failed as an artist. When I was working in advertising, I’d come into the office and there would always be some guy, a freelancer, answering phones. And he was always in his 50s or 60s, wearing a jacket where it was clearly like, that’s the jacket he wore while doing temp jobs. And I always wondered who that person was, why he was answering phones at 60 or 55. And so that’s my fear, is that as an artist, I haven’t made it, I haven’t succeeded. The whole project is not about fear of death or fear of mortality. It’s fear of unpredictability, of life betraying you in some way.

So that’s worse than having a stroke?

PT: Sure.

When watching the film, I wondered if you’d tried any more traditional avenues for lessening fear before doing this project. Did you, say, try Xanax first? Or did you just launch straight into dressing up as depressing future versions as yourself?

PT: I just launched straight into it. In retrospect, it would’ve been a lot cheaper to just go to a shrink.

But not as entertaining for other people.

PT: For me, I always feel that ideas have a gravitational pull. They pull me towards them even if I don’t want to do them.

Joshua Seftel: When my mom watched the movie, she said, “I think like maybe he needed some mood elevators and a psychologist.”

Toledano as a plastic surgery addict

Are you an artist who feels like, on some level, you need dark emotions to fuel your work?

PT: No. But the last five or six years of my life have involved confronting a lot of things I didn’t want to confront, like the death of my sister [in an accident, when I was six years old], and the deaths of my parents.

JS: I don’t think you knew going into it that that’s what this project was about.

PT: Initially, the project was going to be about my past and my future. Then it turned into just my future, enacting all possible things, good and bad. But soon, it evolved into just focusing on the bad.

Well, good things can be boring. People don’t really want to watch other people being happy.

PT: I was so imbalanced by the death of my mother and taking care of my father as he aged that I felt like I had to deal with everything, to unpack these boxes. Until your parents die, for the most part, we all, if we’ve been lucky, have a sense that we’re slightly in control of our lives, that we know where we’re going and how we’re getting there.

But death is ridiculous. When my mom died, it just seemed stupid. It seemed improbable. You know in an abstract sense that it’s going to happen, but when it happens, you want to say ‘Let me speak to the manager, there’s been a mistake.”

In the film, Toledano says he felt like he had to do this photography project in order to “get better.” Did the project achieve that? Did it have a therapeutic effect, or was it destructive, like Toledano’s wife thought it would be?

PT: The thing for me was not the end result, it was the process. There wasn’t a particular time when I woke up and thought, I feel amazing. But over the course of three years, I found I felt lighter than I did before.

JS: As an observer of this art project, I thought there was a lot of power in collecting these images. We all have fears of our future, but we push them down. Most of us try not to think about it. For a second, you’re like, “Oh my god, I’m gonna get old,” but you push it away and go watch TV or something. Here, we’re saying, what if I’m not only not going to push it down, but I’m going to imagine, in a specific way, many of the worst possibilities, and I’m going to just lay them out on a table and look at them all. I think the process of putting all those images out there instead of pushing them down was liberating. Letting it all out made it tangible, instead of having the fears be these imagined things you’re repressing. And people watching the film are exploring their own fears while you explore yours.

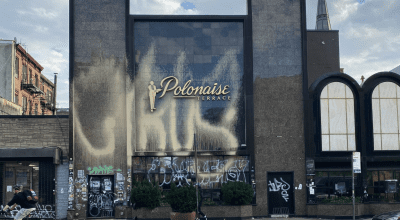

Still from “The Many Sad Fates of Mr. Toledano”

Joshua Seftel and Phil Toledano

All photos courtesy Joshua Seftel and Phil Toledano.

Follow Carey Dunne on Twitter @CareyDunne

You might also like