Brooklyn Guidance Counselor Fired After Vodou Allegations

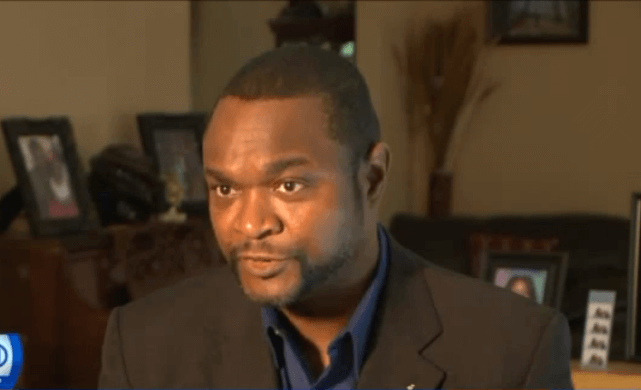

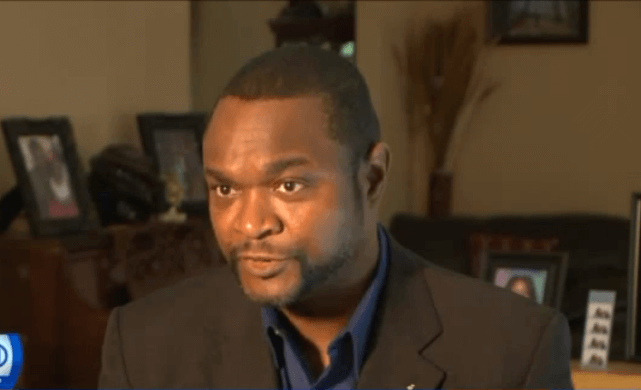

Stevenson Petit, the Brooklyn-based, Haitian-born guidance counselor fired after the principal accused him of being a Vodou priest.

New York City is home to the the largest community of Haitian immigrants in the United States, with the majority–about 90,000–living in Brooklyn. Vodou, Haiti’s most widely practiced religion, has a strong and vibrant presence in the borough. But it’s still widely misunderstood, and often feared, by outsiders. This is illustrated most recently in the case of Stevenson Petit, the Haitian-born guidance counselor at It Takes a Village Academy in Flatbush, who was fired this month after the principal filed a complaint saying he was a Vodou priest.

“I’m a voodoo ambassador. There’s nothing wrong with being a Christian and a voodoo minister,” Petit told the New York Post. In 2012, ITAVA principal Marina Vinitskaya first filed a complaint with the Board of Education accusing Petit of being a Vodou priest (he’s not, in fact, a priest of the religion). After an investigation, the DOE dismissed the complaint. But on July 8th–after Petit’s office had been moved to a basement room once used as a storage closet–Petit received a letter from Vinitskaya saying his position was no longer needed and he was being “excessed.” “She’s trying to get rid of me because I have a Haitian background with a voodoo culture. It’s discrimination.” Petit has filed a discrimination complaint and is lobbying to get his job back.

The principal, of course, denies allegations of discrimination. But if it’s true that Petit was dismissed because of his religious practices, his story is indicative of the widespread misconceptions about Vodou and how many Americans see it as somehow categorically different from other world religions. If the story were about a guidance counselor being fired for working a, say, as a rabbi, or an Episcopalian priest, it would likely be causing more of a public outcry.

“There are many aspects of the religion that might seem strange to outsiders, but I always like to imagine outsiders looking at my own co-religionists, with their shawls and hats and knots and sidecurls, and boxes strapped to their heads, and their awkward movements of worship and prayers intoned in an ancient language,” Wilentz writes. “To me all this seems familiar, to a degree, but to a Haitian Vodouisant or to a Roman Catholic, perhaps not so much.”

“We take this allegation [of discrimination] very seriously and are looking into the matter,” the city Department of Education said in a statement.

[via The New York Post]

You might also like