Both/And: Finding Grace in Flannery O’Connor

I chose for my confirmation name Ignatia. The runner up was Seraphina, after the rank of angels. Of course this is what happens when you let twelve-year-olds choose new names. I wanted flame and, failing that, flight.

During my eighth-grade year, my CCD class prepared us for confirmation, the last of three sacraments of initiation. This would seal our commitment to the Catholic Church, mark our full participation as adults in the communion of saints, and bestow upon us the gifts of the Holy Spirit. An abbot anointed our foreheads with a holy oil called Chrism, which yes does sound like jism (especially if you are twelve), and which we whispered was cut with Crisco. This oil was also at the same time the Holy Spirit itself: both fully vegetable shortening and the flame of belief. But this is just the stuff of Catholicism. We were long accustomed to the duality of everyday objects.

The Holy Spirit offers seven gifts: wisdom, understanding, counsel or good judgment, knowledge, fortitude, piety, and wonder and awe—a collection of intellectual virtues and moral characteristics. Our CCD teacher instructed us to think about them as if they were something that would be put in a shoebox and stored in a closet, things we would have, post-confirmation, but with some work. Like Christmas ornaments in the attic, they would be there when we needed them.

She asked us to pick one of the seven, a particular gift to ask for and pray toward. My heart (or rather, my head) belonged to the intellectual virtues: wisdom, understanding, knowledge, good judgment. At this stage I was a believer, of a sort—at least, I believed that something would happen during this ritual. And so though I wanted, badly, to be wise and knowledgeable and understanding, this was a moment for me to ask for something I sorely lacked. I chose wonder and awe.

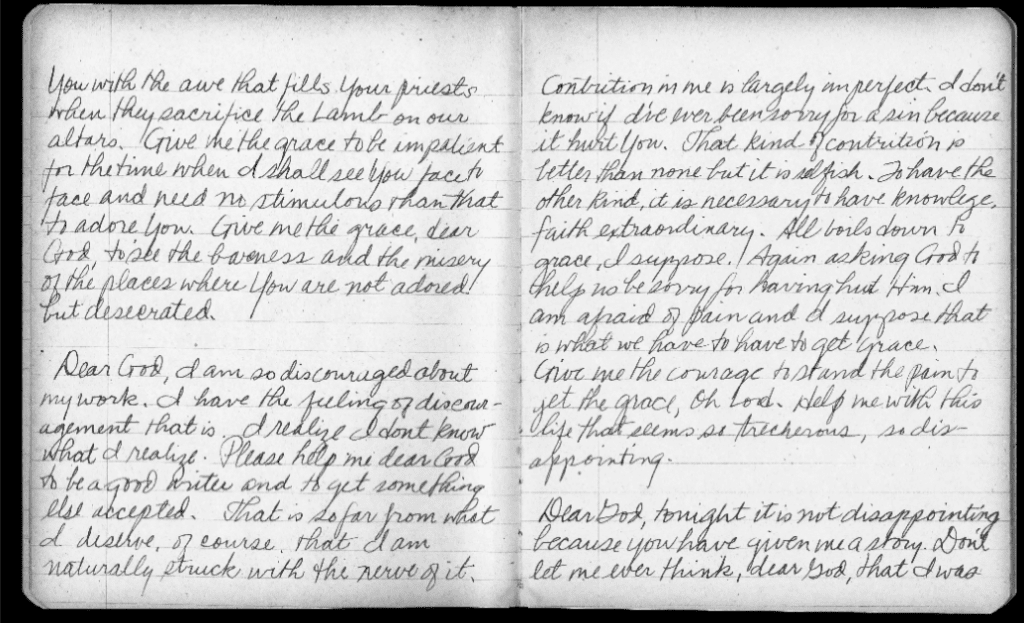

“It is the adoration of You, dear God, that most dismays me,” a young Flannery O’Connor wrote in an undated entry sometime between January 1946 and September 1947. She was at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and she was keeping a log of her prayers—written, literary objects—to God. “I cannot comprehend the exaltation that must be due You.”

I’m reluctant to call O’Connor our preeminent Catholic writer, though she most assuredly is, because she is also not just that. To be called a Catholic writer, or any kind of religious writer, these days is to emphasize the belief over the writing. But O’Connor’s devotion, which so deeply informs her work, does not limit her talent but refine it, burning her work down to a clear blue flame of perfection. Or, as anyone who has read her short stories can attest, the closest thing to it the form can get.

O’Connor was twenty when she began the notebook, published in 2013 as A Prayer Journal. Her prayers read more like letters, alternating between the pleading tone of a supplicant and the chummy intimacy of a school friend. They also grapple with the call to recognize the overwhelming majesty of the divine.

“Intellectually, I assent: let us adore God. But can we do this without feeling? To feel, we must know.”

In one-on-one meetings with our CCD teacher, each student had to explain which gift of the Holy Spirit we had chosen and why. Though it’s certainly a serious question—for the options, if you believed in their reality, were substantial—the conversation had the gravitas of picking through a Whitman sampler. But perhaps that’s why I chose wonder and awe—because my reaction to the offering itself had already made clear what I needed. Wonder and awe was also the most visceral of the gifts, maybe excepting certain forms of fortitude. They were feelings, after all, and so rooted in the body. I dimly understood that this gift promised a physical knowledge of God, and so a kind of proof. It was a way into belief.

Knowledge of God, the Church teaches, comes to us through and because of God. One cannot know God without him intending it, one way or another. It is grace that provides the way, the means.

The Catholic Church makes a habit of eking past tricky theological puzzles with a generous application of both/and. If there are three distinct divine persons, how are they also one God? Both/and. If Christ is divine, how can he also be human? Both/and. If this is bread, how can it also be body? Both/and. If God knows who among us will be saved and who will not, does free will exist? Both/and. If God is omnipotent, how does anything we do matter? Both/and. If Christ saved humanity by dying on the cross, why must we be individually saved? Both/and. Get used to this—it’ll be the answer to most of your questions.

Thomas Aquinas, the pudgy Dominican to whom Catholicism owes its most elegant both/ands, delineated two kinds of grace: gratia gratum faciens (literally, grace that makes acceptable) and gratia gratis data (grace freely given), also known as sanctifying and actual grace. The former is stable, given to a soul (for grace is always a gift) for it to keep. Like a kind of membership, it can only be disposed of purposefully, by (say) tearing up your spiritual gym card or committing a mortal sin. (Baptism, along this line of thinking, is the initial member contract.) The latter grace, actual grace, refers to moments of divine intervention: this grace lasts only as long as the intervening act itself. Actual grace is the movement of God.

Flannery O’Connor obsessed over the question of grace, both in her journal and in her fiction. “You say, dear God, to ask for grace and it will be given. I ask for it,” she wrote. “I realize that there is more to it than that—that I have to behave like I want it.” Her desire is written across the journal; grace, mentioned in nearly every entry.

Grace represented a path to knowledge for O’Connor. “I want to be intelligently holy,” she wrote in November 1946. “Will I ever know anything?”

Grace for her offered a way out—out from intellectual suffocation, out from ignorance, out from fear, out from pain. But there is anxiety, too, and reluctance. “Help me to feel that I will give up every earthly thing” for grace, she asks, but qualifies, “I do not mean becoming a nun.”

“Please don’t let [grace] be as hard to get as Kafka made it.”

In these entries, divine knowledge, grace, and pain are inextricable. Pain is a path to grace (or at least pain becomes bearable with it), and so pain/grace also connects one to God, and for O’Connor’s purposes, to God’s love. And while that love, for her, lacked physicality, it also promised an end to suffering.

“I do not want it to be fear which keeps me in the church,” she wrote, “but I believe in hell. Hell seems a great deal more feasible to my weak mind than heaven. No doubt because hell is a more earthly-seeming thing. I can fancy the tortures of the damned but I cannot imagine the disembodied souls hanging in a crystal for all eternity praising God.”

“The point more specifically here is, I don’t want to fear to be out, I want to love to be in.”

While she wrote these entries, O’Connor worked on what would become her first novel, Wise Blood. A hard nut of a book, it offers few answers. Hazel Motes, a World War II veteran who has struggled with his faith forever, attempts to free himself from a horrifying vision of Christ—“a wild ragged figure motioning him to turn around and come off into the dark”—by founding a church without him: the Church without Christ. The ferocity of his resistance has the strength of a Pentecostal flame, but his efforts are more towards firefighting than anything: to put out, at all costs, the vision of the wild figure moving “from tree to tree in the back of his mind.” Hazel’s ultimate violence against himself—rubbing his eyes with quicklime—extinguishes his sight. Self-immolation gives Hazel his only modicum of peace.

An anti-minister of a non-church, Hazel finds few followers, and chief among the handful who notice him is Enoch, who O’Connor later, in the posthumous collection of prose Mystery and Manners, called “a moron and chiefly a comic character. I don’t think it is important whether his compulsion is clinical or not.” A fool, in other words, and, as bearer of the titular “wise blood”—a prophetic, if inscrutable, gut feeling—a holy one.

Paul, the bald, bow-legged evangelist who brought a young and floundering Christianity to the world, wrote in his letters to the believers of Corinth most eloquently on the tension between religious illogic and secular thought. “Hasn’t God made foolish the wisdom of this world?” he asks. “The foolishness of God is wiser than men.”

O’Connor has no interest in a middle ground, a point halfway between idiocy and intellect. The specter of mediocrity haunts her journal—the prospect of being a lukewarm Catholic, an unexceptional writer, is a miserable one. In an entry dated November 6th, she wrote, “I think to accept it would be to accept Despair.” A few months later, on January 11, 1947, she elaborated: “I’d rather be less. I’d rather be nothing. An imbecile.”

Enoch is that imbecile, and even if he was intended to be chiefly comic, he is not simply that. His blood, after all, names the novel. He not only doesn’t know what orders him about, he also doesn’t need or want to know: “Enoch never nagged his blood to tell him a thing until it was ready.” He is comfortable in his ignorance, and though his decisions don’t make sense—he kidnaps a small mummy from a museum, he kills a man for his gorilla suit—he rarely experiences unrest or doubt. In his last appearance in the novel, he has become the gorilla: animal, perfect, simple. A child of God.

Hazel has none of Enoch’s easy faith. While belief itself (that Jesus exists, that he redeemed the world’s sins) has never posed a problem, his Christ is the stuff of nightmare. Everything about that “wild and ragged figure” signals danger, and danger is what he represents for Hazel. His Jesus invites him to come into the darkness, to where Hazel “was not sure of his footing, where he might be walking on the water and not know it and then suddenly know it and drown.” Most perilous, for Hazel, is the not knowing, and then the knowing too late.

Many years after I was confirmed, probably during some late-night Wikipedia ramble, I came again upon the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Even then, firmly entrenched in my atheism, I had felt some pride for the gift I had chosen. (Ignatia did not age as well.) Wonder and awe represented for me a specific experience, not unlike seeing an IMAX movie at the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum, a slow zoom out from everyday life into the infinity of the cosmos. This view of God would have been precisely the opposite of Hazel’s, broad where his was narrow, bright where his was dark, safe and spectacular where his was dangerous and quotidian. A cool gift, a good gift. Yet when I looked at the list again, wonder and awe did not appear. Here, the seventh gift was called “fear of the Lord.”

In the official catechism of the Catholic Church, this gift of the Holy Spirit is indeed called “fear of the Lord,” though in the English translation of the Latin Rite, the confirming bishop uses the term “wonder and awe” as he calls the Holy Spirit and its gifts down onto the heads of the confirmed, his hand raised in a gesture of blessing.

I understand the rebranding. Who wouldn’t? It’s hard to get excited about fear—though the Church is eager to affirm that this fear is a filial one, a fear of hurting the beloved; rather than servile, a fear of punishment. (Though, as one priest-columnist noted in the Arlington Catholic Herald, you should probably be afraid of punishment too.) This is the difference between the obedience owed a loving parent and the obedience owed a master. The Church uses these two metaphors—borrowed from 4th-century theologian Basil the Great—to describe the kinds of relationships one can have with God. Pick one: child or slave.

All Hazel has is fear—fear of God, fear of the unknown—but he has no interest in the choice it offers him. O’Connor too, in her prayers, wanted so much more than fear. She wanted knowledge. She wanted grace. “I don’t want to believe in hell,” she wrote, “but in heaven.”

“Stating this does me no good. It is a matter of the gift of grace.”

Later on, in her nonfiction, O’Connor wrote about the violent core of so many of her stories. It is a matter of physicality, of disrupting the body to right the mind.

I suppose the reasons for the use of so much violence in modern fiction will differ with each writer who uses it, but in my own stories I have found that violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept their moment of grace. Their heads are so hard that almost nothing else will do the work.

Here again violence, pain, serves as a conduit for grace. O’Connor was far from alone in making this connection—it’s a tradition that reaches all the way back to Paul, and further on to the Crucifixion itself.

“Suffering,” Paul says in a letter to the Christians of Rome, “produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit, which has been given to us.

Official Catechism promises that the flip side of fear is hope. Aquinas clarifies that filial devotion creates not a fear of failing “what we hope to obtain by God’s help” but of “withdraw[ing] ourselves from this help.” This fear is the fear of losing someone, of hurting someone, and so it is born out of the love that feeds the hope for future happiness with that same someone. Fear of punishment decreases when hope increases, Aquinas writes, but filial fear increases along with it. Similarly, Aquinas takes his theologian’s scalpel to punishment, carving out an argument that it is both a relative evil, because it is caused by a privation of good, and an absolute good, because it is just. Both/and. I warned you.

In Wise Blood, both Hazel and Enoch kill people who have taken their identities, or whose identities they want to take. But these people, as doubles, seem to not really count in the moral universe of the novel: they do not prevent either Hazel or Enoch from reaching a state of grace, or at least equilibrium. In both cases, these acts of violence—these mortal sins—begin each character’s transformation. Late one night, Hazel runs over his double, Solace Layfield, a man hired by the huckster Hoover Shoats, who created his own Church of Christ without Christ after Hazel’s Church without Christ. (Shoats’s version had one Christ too many for Hazel’s taste.) The next morning he leaves to start the Church without Christ afresh in a new city, but on route he’s pulled over by a mysterious patrolman who, after learning that Hazel doesn’t have a license, pushes his car over an embankment to its destruction. Hazel then walks the three hours back to his lodgings, buys a bucket of quick lime, and burns away his sight.

It’s a puzzling series of events, one that doesn’t make a lot of sense according to the rules of the world. But there’s something in this reminiscent of Paul’s journey to Damascus: he is thrown from his horse, he is blinded, he believes.

“I am afraid of pain,” O’Connor admits in one prayer. “I suppose that is what we have to have to get grace. Give me the courage to stand the pain to get the grace, Oh Lord.”

O’Connor was confirmed on May 20, 1934, in the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Savannah, Georgia, where she was baptized nine years before. The Church teaches that confirmation acts as a final installment of the sanctifying, stable grace we initially receive at baptism (now with one free Holy Spirit!), but that kind of grace seems to offer her little against the challenges presented by fear, by pain, by mediocrity, by the task of writing. In her journal and in her fiction, O’Connor chases the fleeting, incendiary power of actual grace, perhaps because it is something that must be sought after, earned in a way the grace bestowed by the sacraments is not.

“Giving one Catholicity”—a great noun—“God deprives one of the pleasure of looking for it,” O’Connor wrote, “but here again He has shown His mercy for such a one as myself—and for that matter for all contemporary Catholics—who, if it had not been given, would not have looked.” She feels grateful to have been born into Catholicism, but who can blame her for wanting to have pursued and then found it on her own. It would have made for a better story.

While all confirmed Catholics receive the mark of holy oil, taking a confirmation name—i.e., choosing among the saints or blessed for a symbolic protector and guide—is a custom most common to English-speaking Catholics, and goes unmentioned in the official catechism. Everyone in my confirmation class took them: there were all manner of Theresas and Matthews, Catherines and Johns. When O’Connor served as sponsor to her correspondent Betty Hester’s confirmation, the latter, at 34, chose the name Gertrude. All reasonable, and often attractive, names. I, on the other hand, picked one which was neither.

I had found it in a book of religious names for women. Ours was a Jesuit parish and so the name appealed to me for reasons of allegiance. (Ignatius of Loyola had founded the Jesuit order; Ignatia was the female form of his name.) The deciding factor, though, was its definition: underneath the name were the words in italics: “ardent, burning.” I, a pale and breathy preteen, had more in common with a damp sponge than anything aflame, but I suppose I wanted to burn with something—anything—even if it was the Church.

This axis between meta- and physical, I think, is key—to Hazel’s story, to O’Connor’s, to mine. It’s about the necessity of a bodily experience of God, to connect the “earthly-seeming” Hell to the eternally disembodied and crystalline Heaven that O’Connor describes in her journal. After all, as she wrote in a January 1947 entry, “The devil is the greatest believer & he has his reasons.”

Blind, Hazel’s relationship to his body deepens, complicates. He wraps his chest in barbed wire; he fills his shoes with stones. He’s gone into the darkness, and found something there. “If there’s no bottom in your eyes,” he explains to his landlady, “they hold more.”

She calls him crazy. “What possible reason could a sane person have for wanting to not enjoy himself any more?” But Hazel has abandoned earthly wisdom. Where before he wanted to stay in his hometown “with his two eyes open, and his hands always handling the familiar thing, his feet on the known track”; now his eyes are gone, the world unfamiliar, the track—more or less—unknown.

But the peace he finds in this foolishness, in the punishment he requires his body to pay, is palpable. What can this be if not grace? In death, he appears tranquil, composed. Faced with his corpse, Hazel’s landlady, who has become infatuated with him:

shut her eyes and saw the pin point of light but so far away that she could not hold it steady in her mind. She felt as if she were blocked at the entry of something. She sat staring with her eyes shut, into his eyes, and felt as if she had finally got to the beginning of something she couldn’t begin, and she saw him moving farther and farther away, farther and farther into the darkness until he was the pin point of light.

O’Connor later wrote in her nonfiction that “it is the free act, the acceptance of grace particularly, that I always have my eye on as the thing which will make a story work.” It’s a radical decision, to pivot the plot of any given narrative on the movement of grace through it. “What is needed is an action that is totally unexpected, yet totally believable,” she went on, “and I have found that, for me, this is always an action which indicates that grace has been offered.”

And this is where O’Connor draws her line in the sand. “That belief in Christ is to some a matter of life and death has been a stumbling block for readers who would prefer to think it a matter of no consequence,” she remarked of Wise Blood. “For them Hazel Motes’ integrity lies in his trying with such vigor to get rid of the ragged figure who moves from tree to tree in the back of his mind. For the author Hazel’s integrity lies in his not being able to.”

What’s remarkable about her prayer journal, compared to her nonfiction, is its openness. And of course it is open: it was written to, for, God. But O’Connor’s essays have so little give in comparison: there she is flinty, pedantic, firm. She writes as someone who knows she will not be believed. In her prayers—despite her questions and doubts, desires and regrets—she is the most at ease. There she is alone with her belief, alone with God.

“It is hard to want to suffer,” she wrote, “I presume Grace is necessary for the want.”

Four years after she stopped keeping her prayer journal, O’Connor was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus, the disease that killed her father a decade earlier. It changed the tenor, and certainly shortened the span, of her life: she retired to Milledgeville, Georgia, in 1951; took up crutches in 1955; and died in 1964, thirteen years after her diagnosis. It’s striking to look at these prayers, written between her father’s death by lupus and her own diagnosis with it, with their attention to suffering, their tacit belief in suffering’s necessity, and their hunger for grace, which would be suffering’s salve.

She ends the journal in a fit of self-disgust. “My thoughts are so far away from God,” she scratches out. The ink is thick and dark on this page. “He might as well not have made me. And the feeling I egg up writing here lasts approximately a half hour and seems a sham.”

“Today I have proved myself a glutton—for Scotch oatmeal cookies and erotic thought,” she concludes. “There is nothing left to say of me.”

I never did feel what I expected to feel—the effects of grace, the movement of the Holy Spirit—during my confirmation mass, though I don’t blame the Church, or the Church’s idea of God, for that. I took enough religion classes to know that God rarely acts in ways one would expect. Belief is merely absent. Still, I hear myself in O’Connor so often in this journal. “At present I am a cheese,” she writes, “make me a mystic, immediately.”

“God can do that—make mystics out of cheeses.”

I like to believe that O’Connor eventually felt the grace she so badly wanted. I like to believe that mystics, of some kind or another, can be made out of cheeses. And I like to tell myself, even now: both/and, both/and, both/and.

Follow Molly McArdle on twitter @mollitudo

You might also like