Why Poor and Violent Equals Black: Or How the Media Distorts Our Perception of Black America

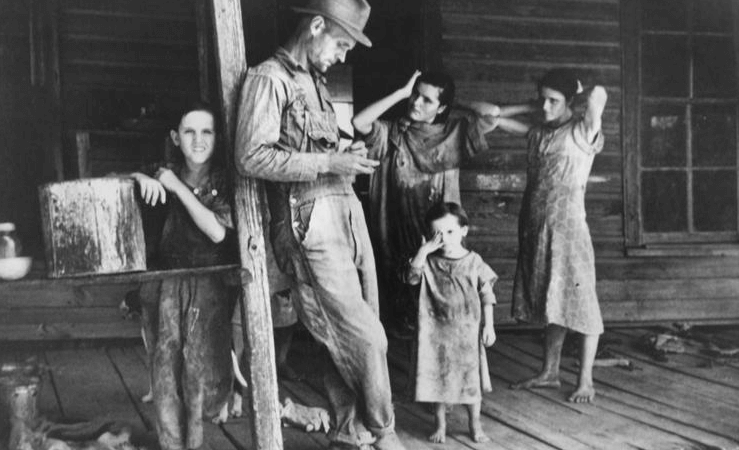

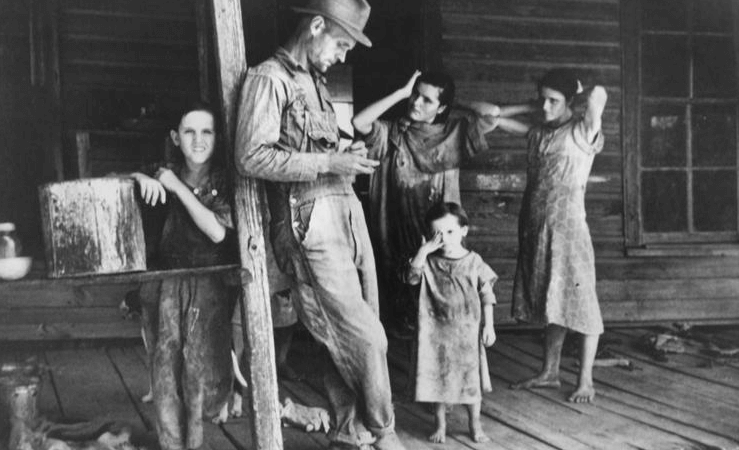

This white family would no longer be considered the face of poverty in America

Right now, thousands of people in Baltimore are protesting the death of Freddie Gray at the hands of city police. Gray died on April 19th of a spinal injury sustained following his arrest in West Baltimore on April 12th, when he was detained for what appears to be the singularly non-criminal action of side-eying local cops and running away. As The Atlantic reports: “According to the city, an officer made eye contact with Gray, and he took off running, so they pursued him.” Gray was found to be in possession of a switchblade, but, as Baltimore mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake correctly noted, “We know that having a knife is not necessarily a crime.”

And yet, a black man’s actions not necessarily being a crime have never been enough to prevent him from being the object of excessive force on the part of the police. Such appears to be the case with Gray, who was arrested and placed in a police van and brought to the station. At some time during this period of transit, three of Gray’s vertebrae were fractured and his voice box was crushed, injuries consistent with severe car crashes. The situation is being investigated, but no arrests of the officers involved have been made. And so, much of the city of Baltimore has risen up in protest.

In a surreal reprisal of the coverage surrounding Michael Brown’s death and the protests in Ferguson, much of the media attention has focused on the looting and violence of part of the protesting population, implicitly inviting commentary that condemns all the protestors’ actions, while ignoring the reality of what incited the riots: state violence against an all but disenfranchised segment of the population. The fact that the media promotes this idea of the protestors as being nothing more than a mindless mass of people, swept along in a wave of anger and emotion that has nothing to do with thought and everything to do with scattered rage, should come as no surprise to anyone who thinks back to Ferguson and the way the protestors were portrayed there, to say nothing of things like the way that the New York Times opened up its profile of Michael Brown with the remark that he was “no angel.” Most media, after all, is as culpable as any other entrenched institution for wanting to maintain the status quo, no matter the costs.

Lest you think that this type of action by the media is limited to situations like the protests in Baltimore or Ferguson, and that the biased coverage is a function of the specificity of this type of incendiary event, a new study by Bas W. van Doorn explores the media’s representation of poverty in pre- and post-welfare America and has found that the media disproportionately portrays the face of poverty in America as being overwhelmingly black. Joe Pinsker writes in The Atlantic that the study examined almost 500 articles written in publications like Time, Newsweek, and U.S. News and World Report between 1992 and 2010, and found that “in the images that ran alongside those stories in print, black people were overrepresented, appearing in a little more than half of the images, even though they made up only a quarter of people below the poverty line during that time span.” In Newsweek alone, the difference between the reality of black Americans’ existence and how it was portrayed is shocking: “80 percent of the people pictured alongside Newsweek‘s stories on welfare were black,” even though only 38 percent of Americans who receive welfare are black.

In fact, these discrepancies in how black people are portrayed in the media is reflective of how inaccurately most Americans view the country’s black population on their own:

In 1991, a survey found that Americans’ median guess at how many of the country’s poor people were black was 50 percent, though at the time the actual figure was 29 percent. Ten years later, another poll found that 41 percent of respondents overestimated the percentage by at least a factor of two. (In 2013, 23.5 percent of America’s poor were black.)

So despite the fact that the majority of welfare—including food stamps—recipients are white, Americans remain enthralled with the idea that it is black people who are the face of poverty, black people who rely on welfare and food stamps, black people who riot and loot and burn whenever they get the chance. The damage that this does to the black community in this country is incalculable; by othering the black experience—even when millions of white Americans share that exact same reality of poverty and government assistance, to say nothing of rioting—the media helps to promote the conservative agenda which seeks to further marginalize an historically oppressed, enslaved population of people by insinuating that black Americans are unworthy of aid—or even compassion—because they are solely responsible for their own poverty, and their own oppression.

There is little doubt that it will take time, effort, and education in order to change the entrenched ideas that many people have of black Americans, but an important start would be a more accurate representation of who in this country truly benefits from a governmental safety net (spoiler: we all do), so as not to continue to stigmatize and marginalize only the black community. Seeing is believing, after all, and when all people see—day after day, year after year—are images of black faces and bodies associated with poverty and violence, people don’t know what else to believe. Lest anyone think this task is impossible, think only of the rapid evolution in the acceptance of gay marriage in this country, and how much the cause was helped by positive media portrayals. Equality in media portrayal is not an unreasonable goal, but it is one that is necessary in order to move forward, to change our perception of the present, to rewrite the future.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like