“Project Lives” Documents Life in the Projects From the Inside-Out

“I love how when I’m in the school, hallways are so quiet when I walk through it’s just great because you can just hear yourself think about how you are going to plan once you get in class. Just stay focused on what’s around you.”

photo and quote by Aaliyah Colon

Tonight at Power House Arena you can pick up a copy of Project Lives, a new book of photographs taken by dozens of New York City public housing residents. The book’s editors—George Carrano, Jonathan Fisher, and Chelsea Davis—have also been at the helm of Seeing for Ourselves, a non-profit participatory photography initiative to bring photo workshops (called Developing Lives) to NYCHA tenants.

“The three of us came together around this idea of turning over the narrative of public housing to people living there, as opposed to allowing Hollywood movies and tabloids to define their reality,” Fisher explained. “It was a chance for them to go out and record their daily lives and to establish the contrast between the way they actually live and the way they’re portrayed.”

All three editors have disparate backgrounds: Carrano is an activist documentary photographer and founder of Seeing For Ourselves, Fisher has a background in transportation science, and Davis is an educator. However all of them found common ground with Carrano’s photography initiative, the central aim of which is to change policy that effects a large number of New Yorkers. They hope that by getting the attention of lawmakers, and by showing that New York City Housing Residents are not only in need of help, but in need of reconsideration, they can help revive the projects to their former functioning, albeit spartan standard.

“What [our representatives] haven’t seen, what’s new here is this fresh, positive view of public housing projects and we see that the people who live there are just like us,” Fisher explained.

The resulting photographs are flash heavy, well-composed images of people, objects, and images of the infamously iconic aspects of the projects—poorly lit stairways, crammed apartments, and towering, monolithic, brick buildings. Some are surprisingly empty and lonely for having been taken in what’s essentially a communal environment, while others ring brightly with activity and familiarity—the subjects look back at the photographer knowingly, sometimes lovingly.

“I think it’s natural when someone is taking a picture of someone else, the subject becomes really self-conscious in front of the camera and that sense of self-consciousness isn’t really seen in our photographs,” Davis said. “You can tell the photographer has a relationship with the subject.”

This relationships renders the heavy flash—something associated with othering, placing outside of, and distancing—out of place. But the stark lighting wasn’t the aim of the photographers, instead it was a by-product of the project’s limitations. Workshop students were given one-time use, disposable cameras as opposed to any number of other options for cameras.

“On Christmas I photograph my cat and I dance with my cat. Dance ballerina, because you like the music. She likes that I dance and I feel content. She is as happy as a person. I love my cat.”

photo and quote by Susana Ortiz

Photo by Margarita Curet

Davis explained why digital wasn’t a desirable option: “The photographers were limited to 27 photos per week, which is actually really nice because it made them think about each and every photograph they were taking. They didn’t have a digital camera that they could just take a million pictures with.”

I couldn’t help but wonder, if it had to be film (to which I’m actually partial) why couldn’t Seeing for Ourselves at least acquire point-and-shoot cameras? Or better yet, cameras where the students would be allowed to adjust for focus, aperture, shutter speed, and ISO—any number of choices that would give them more creative leeway as photographers, and above all more control. Was this another case of failing to trust public housing residents? Another way of devaluing peoples’ lives who are of lower socioeconomic status, simply because they are in need of government assistance?

Then again, perhaps the money wasn’t there. However, point-and-shoot cameras, which offer at least a modicum of control (loading and unloading film, winding), are easy to find for even less than the price of a disposable camera. And buying film in bulk (roll your own!) would make things way more economically viable and educationally salient than disposable plastic boxes.

But Davis pointed out single-use cameras encouraged people to focus more on content. “It really focuses in on subject matter—that’s the only thing you really have control of,” she said. And the photographers were also in charge of writing their own captions, all of which made it into the book.

Carrano explained the book was integral to the non-profit’s mission from the outset of the project back in 2010. “We’re trying to get more eyeballs, because it’s going to take a critical mass of viewership in order to shift that perception nationwide,” Fisher explained. “Which is what it’s going to take to restore the projects to their former state.”

The editors are hoping that by bringing an awareness to what life is actually like in the projects, lawmakers and their constituents might understand that people rely heavily on public housing, which is crumbling across the country due to lack of budgetary allocation.

“The backstory in the book is the defunding of public housing,” Carrano explained. “And New York City is the place where it all began and it’s the place where the line in the sand is being drawn in terms of the survival of public housing, so it’s vital we get adequate funding both in terms of capital funding for rehabilitation of the facilities and improvement in the operating budget. We’re hoping the book can change that.”

“Cloud formations. Impending rain.”

photo and quote by Sheik Bacchus

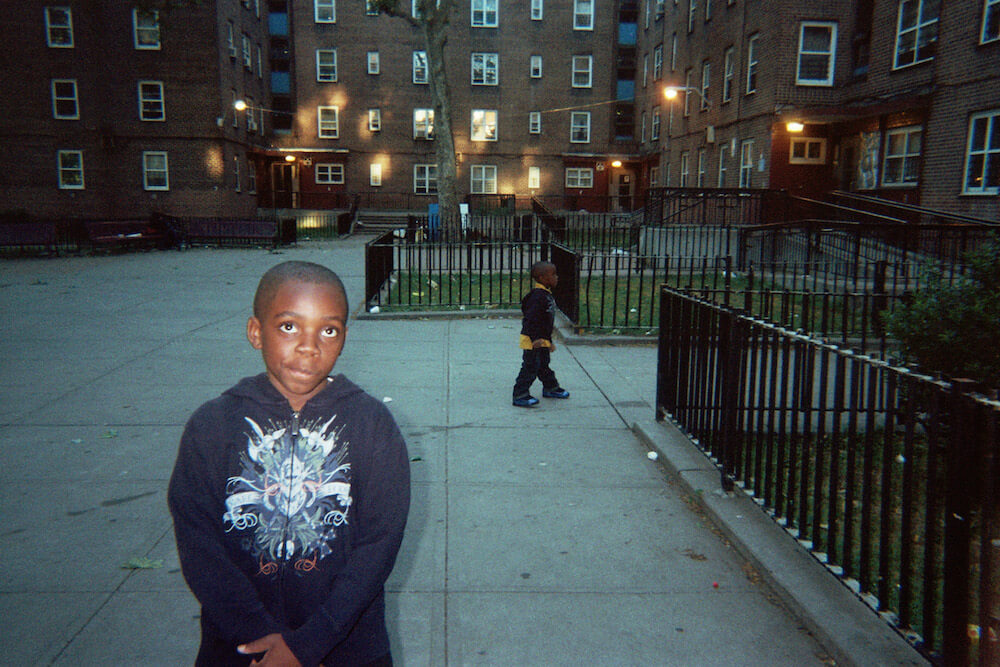

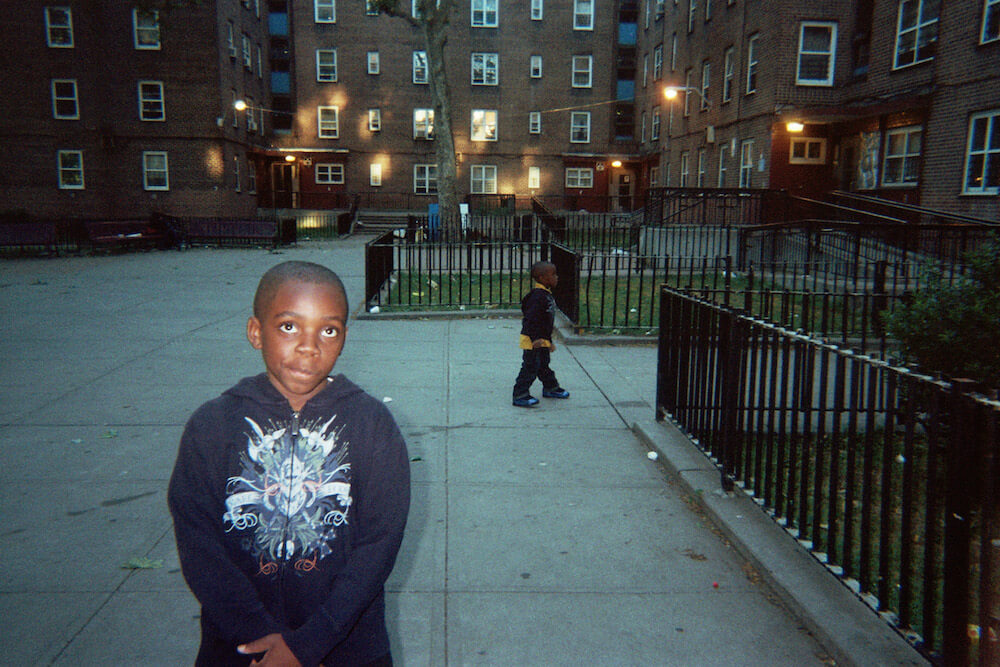

“We roam around this spontaneous block sticking together as brothers. Yet we are cousins.”

photo and quote by Jared Wellington

“The government started pulling back in the 80s,” Fisher added. “We talk about St. Louis a lot in the book because when Pruitt-Igoe imploded in 1972, that kind of sent a signal that the government can’t do anything right. That set off this generation-long devaluing of the public sector and helped create the harsher social fabric we have today, so what you have to ask yourself is—if the New York projects were to fall, not only would half a million people lose their homes, as horrendous as that would be, but what kind of a signal would that send to the rest of the country? And where would that take us?”

Interestingly, the focus of the book is not on decaying buildings, struggle, or a lack of, well, a lot of things. I wondered if photographs that portrayed these realities were edited out.

“There was this big fear of certain parties that we might get something back that was negative, focusing on how the toilets didn’t work or the crime scenes or something. And we didn’t get back any of that,” Fisher said. “To us, that was the greatest joy of the program, that people in such circumstances would focus on the positive. All the pictures are optimistic and speak to the dignity of human life of the people who live in the projects. They did better than me. I mean if I lived in the projects I might be focusing on something else.”

Davis added: “The photographs themselves are just overwhelmingly optimistic and full of pride, pride for their home, pride for their family. And all of our participants were really eager to share their stories and to document their lives and to preserve those moments.”

Carrano agreed: “You see yourself in these pictures and the sense of community—it’s not an alien world, they are New Yorkers, Americans just like us.”

While it’s questionable the degree to which this book lessens the othering of people living in the projects– after all where does the interest of the viewer stem from? Certainly not just from the photographs—the agenda is explicit and seeks to get more resources into the hands of public housing residents (plus, all proceeds from the book go to NYCHA programs). But even if, to a certain extent, there are some problems within all activist art like this, the work can still be enjoyed for the values it promotes: family, friendship, community, and resilience.

You might also like