Let’s Talk About Prison, Everyone

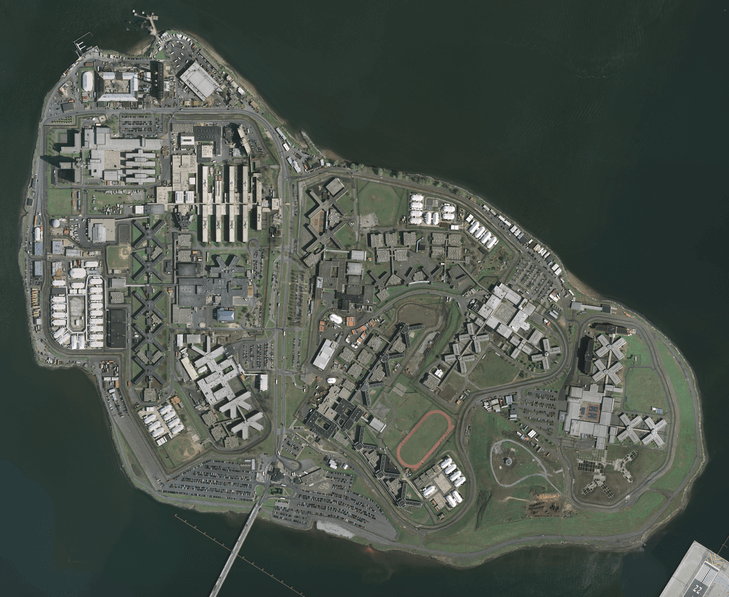

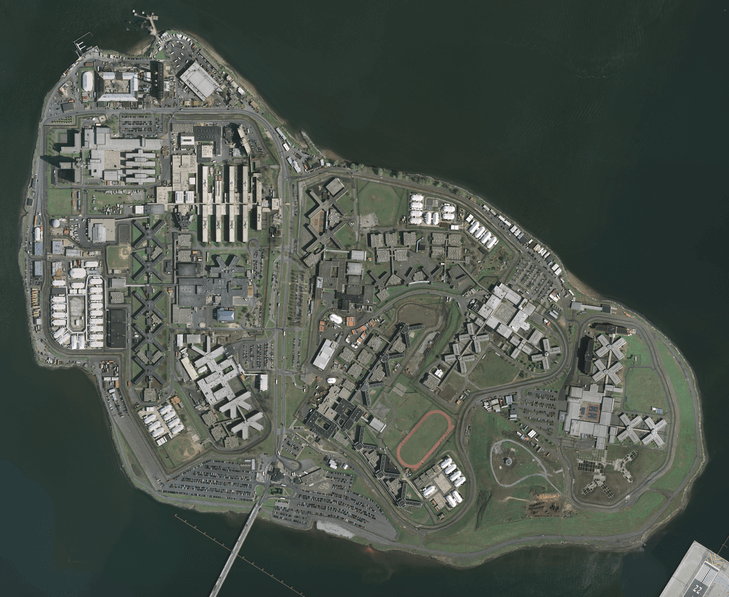

Rikers Island

It’s hard to imagine that most people would really want to talk about their experiences in prison, much less to a room full of buttoned-down academics and other people who have probably never had a run-in with the law, and might never know what it feels like to be put in handcuffs or strip searched. But a new project, Global Dialogues on Incarceration, spearheaded by the New School’s Humanities Action Lab and several other universities from across the country, is working to ensure that the experiences of what it’s like to serve time become shared memories between not only the formerly incarcerated, but also the general public. And given the discussion of police brutality and widespread doubt about whether our justice system is functioning as it should, this initiative is now more relevant than ever.

During a talk on Monday evening at the New School in Manhattan, Glenn Martin, founder of JustLeadership a New York City-based advocacy group working for prison reform, spoke about last year’s report detailing systemic violence at Rikers Island: “That report was a joke to anyone who had ever been there.” Martin, who spent one year of his six years in detention on Rikers before being moved to a federal facility upstate, called the city’s primary jail complex, “probably the scariest place on earth.”

The new project up for discussion at the New School on Monday night (directed by Liz Ševčenko who founded a similar initiative, the Guantanamo Public Memory Project) is about sharing memories of incarceration, and helping people who might be quite removed from the experience (i.e. privileged white people) have a better understanding of the kinds of people who are throw in prison (smart people, innocent people, poor people) and what happens to them while behind bars. Interviews with formerly incarcerated individuals will be documented and shared via a web platform and nationally traveling exhibition. As a social justice project, it inherently has an activist mission: to change what many feel is a broken judicial system. The project relies on the notion that spreading awareness is key, and by using technology and design to disseminate first-hand accounts of life in prison, that the public will have a better idea of what prison is actually like.

Glenn Martin, the son of a cop, grew up in Bed-Stuy and was was arrested for robbery as a young man. During the launch of Global Dialogues on Incarceration, he sat in front of a room of activists and academics, not as a criminal or an “ex-con”, but as one of the most recognizable figures in prison reform activism—Martin has appeared as an expert on and given a number of interviews for big news networks. He has also worked tirelessly for prison reform and advocated for the rights of formerly incarcerated people.

The issue of prison reform isn’t new. Another speaker, Mark Mauer has been fighting mass incarceration since the 70s, when the U.S. prison population was just above 300,000 (it is now more than 1.5 million). But in light of the Eric Garner decision and the Michael Brown case, as well as the deepening chasm in New York City between the police and people who are critical of police brutality and use of lethal force, Martin’s message had a new urgency. “More people are beginning to understand that there’s a problem with the front end of things,” he said. So perhaps, he suggested, getting more people to understand the “back end,” or the prison system, isn’t too far off.

“This machine is in place and it’s a juggernaut of a machine,” he said. “You can be doing all the right things and still be defined as the Incredible Hulk.”

With protests of recent weeks, countless stories have emerged from New Yorkers of color about police brutality, and a sense that the NYPD is not there to protect them. And as if the overwhelming number of individual accounts of systemic racism amongst police officers wasn’t enough, there are statistics to support those stories. Back in October, ProPublica released an investigative report detailing deadly force and an “outsize risk for young black males.” The report found a “stark disparity”: Young black males are 21 times more likely to be shot and killed by police than their white counterparts.

It’s clear that something needs to be done to eliminate racial bias in police departments across the United States. However an essential part of addressing the issue involves looking at why cops police communities of color more aggressively. Are they incentivized to do so?

In this week’s issue of the New Yorker, David Remnick quoted James Baldwin’s essay on police brutality in Harlem, and one passage in particular speaks to this idea that perhaps the police really are just following orders: “It is hard, on the other hand, to blame the policeman, blank, good-natured, thoughtless, and insuperably innocent, for being such a perfect representative of the people he serves.”

That is not to say that all police officers are blindly serving to the public, but to a certain extent as an organization that isn’t wholly separate from the rest of society, they mirror biases that are harbored by the larger society. And as cogs in a massive penal machine, they are simply serving their superiors (i.e. the justice system as a whole).

According to data compiled in 2008 by the Justice Mapping Center, the highest imprisonment rates are in communities that are historically black—East New York, Brownsville, Bed-Stuy—where up to 5 people for every 1000 were admitted to prison that year.

However the most striking numbers to emerge from the Justice Mapping Center’s research reveal how much money the government spends on incarceration. Within the bounds of the 11233 area code, which maps onto parts of Bed-Stuy and Brownsville, $19 million was spent on keeping people in prison. The Center has highlighted what it calls “million dollar blocks,” or single census blocks where millions of taxpayer dollars are invested in imprisoning the population.

Numbers like this never cease to be disturbing, but they have become commonplace. I rarely get the opportunity to admit that I ever listened to System of Down (and believe me, it’s a humiliating prospect), but I do recall their 2001 hit song explicitly addressing the United States’ reigning title of country with the highest proportion of its population in prison. My point being, this information is mainstream—not many people are shocked when they’re reminded of these facts:

-

According to the Sentencing Project, in 2013 more than 1.5 million people were incarcerated in the U.S. State and Federal prison system

-

In the United States, 1 in 3 black men will have a stint in prison (compared to 1 in 17 white men)

-

1 in 18 black women will spend time in prison during their lifetime, whereas that likelihood is just 1 in 111 for white women

-

Across the country approximately 5.8 million people are denied the right to vote because of disenfranchisement laws for Americans with felony convictions

But in thinking about ways to address systemic racism within the ranks of the NYPD and police departments across the country, these numbers must be revisited. Because unless we truly believe that all cops are terrible, sadistic human beings hellbent on making life miserable for all people of color, then we should consider the motivations that drive cops to police communities of color. That’s not to say all police officers should be excused for racial profiling and committing a higher proportion of the violence against people of color.

Even if we’re just looking at the issue from a fiscal standpoint, do New Yorkers really want their tax dollars allocated to keeping people in prison? Particularly those who find themselves behind bars for drug convictions?

As a kid riding the subway yesterday reminded me, “It’s all good as long as you’re not selling drugs.” Her father looked at me when he noticed me laughing and said, “An 8 year-old knows that, but try telling that to the police.”

And as Glenn Martin reminded everyone at the New School event on Monday: “As New Yorkers, we own [Rikers Island]. That’s our jail.”

In the State of New York, prison populations have declined precipitously (at least in comparison to the national average); in 2011, there were more than 17,000 fewer people in prison than there were a decade prior. Yet the racial disparity remains: For every 1 white male in prison there are 9.4 black men.

Among the activist groups that have led the Eric Garner protests in New York City, the Justice League, has brought the issue of imprisonment to the fore. As part of its permanent mission, the Justice League fights youth incarceration and ending the “school to prison pipeline–” a measurable trend demonstrating that young people of color are often punished in public schools for minor offenses, setting off a chain reaction of events eventually leading to incarceration.

Mayor de Blasio made improving conditions at Rikers a top priority and acted relatively quickly after the release of a Justice Department report detailing violence against adolescents to end solitary confinement for youth. The de Blasio administration has also enacted and supported some significant criminal justice reform in ending low-level marijuana arrests and dramatically reducing stop-and-frisk. Yet there seems to be something of a disconnect, and a failure to fully address the “back end” issue, as Glenn Martin referred to it, or what another New School panel member, Liza Jessie Peterson (an actress, poet, and educator who teaches art to prisoners) called “the big black elephant in the room.”

In figuring out how to mend the divide between the city and the NYPD and how to address entrenched racism, we need to take a much closer look at the prison system and the number of motivations driving cops to police communities of color and to inflict violence on young black men and all people of color.

You might also like