Steve Keene, Grandma Moses of Brooklyn

Steve Keene’s garage studio in Greenpoint glows blue on the inside, its light filtering through blue plastic tarps over the windows and skylights. Keene is in his fifties, with the gentle face of a man who has been smiling for most of his life. Wearing khaki shorts and a loose, short-sleeve button-down shirt, he invited me into the studio where he has lived and worked for the past eighteen years. I asked him questions about his work, his process, and the five hundred paintings he’d finished the day before.

Depending on how you count, Steve Keene may be the most prolific artist working today. He estimates that in the 25 years he’s been painting, he’s sold or given away more than 250,000 paintings. “It’s sort of like I’m a baker,” he says. “If you’ve been a baker for 30 years, you’ve sold a lot of bagels.” Keene laughs easily, and often at his own expense. He considers himself a folk artist, and has always aimed to share his work as widely and as cheaply as he can.

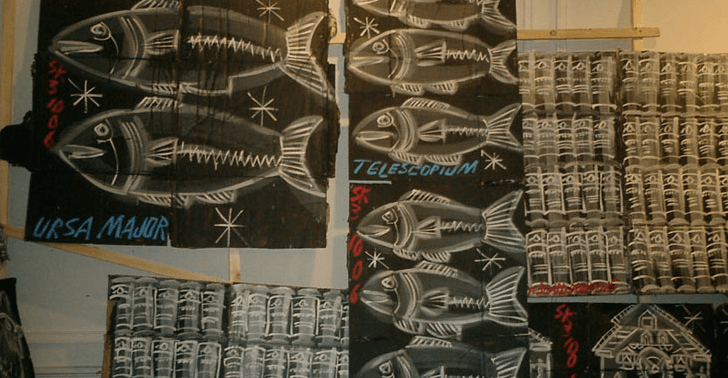

Keene is able to produce and sell so many paintings because of his process. He works on plywood, whole sheets divided into smaller pieces usually not more than 18” on any side, and paints several dozen at a time, making the same stroke on each as he walks around his studio. He does this in what he calls his “cage,” a rectangle of tornado fencing inside the larger studio space, around the interior of which he hangs as many plywood canvases as will fit. His process is not unlike a human inkjet printer, a complete image broken up by line and color then reassembled.

“Back in the day we were friends with people in bands, so there was that sort of performance-work idea. Art’s a thinking thing, but I try to think as little as possible, just blank out and go through the motions, then it normally turns out better than if I sweat about it. I started working this way as a reaction to not having any ideas about what I should do. I was inspired by friends in bands making CDs and cassettes and just trying to get them out into the world, and I just thought that was so positive. Instead of trying to sell your crappy art school painting for five thousand dollars, you sell it like a cassette, for, like, two dollars, and get forty people to have one.”

Music is everywhere in Keene’s work, and not only in its financial theory—he painted the cover for Pavement’s Wowee Zowee, The Apples in Stereo’s Fun Trick Noisemaker, and has painted Keene-ified versions of iconic album covers of the past. “I was doing this in the age of fanzines,” he says. “You’d go to a bookstore or a bar and see a pile of fanzines, and it was that kind of thing, to get my information out real fast. I connected to that feeling, that idea that there’s no hierarchy—just get your information out and then let it sort itself out in the mix. I tried to take any kind of idea of status away from what I did, because I just wanted it to flow. You see the same Pink Floyd album in people’s houses—I like the idea of it having no status, no purpose, no reason.”

In the age of copyright law, it’s rare to hear from someone so staunchly un-precious about the work they produce. Even rarer is hearing it from a visual artist in New York City, where I have personally seen painted trash bags for sale at $5,000 a pop.

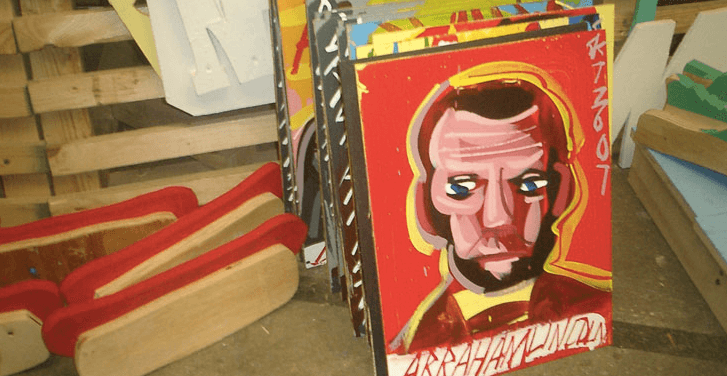

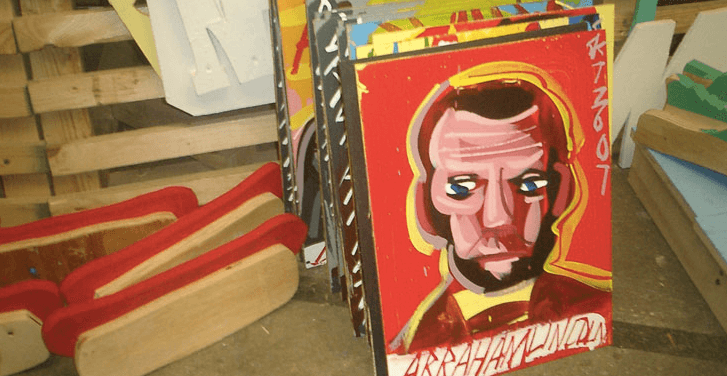

Abraham Lincoln, 2007

Aside from musicians, Keene told me, he’s been been inspired by Gerhard Richter, Sol Lewitt, and Christo and Jeanne-Claude, the artists who created The Gates in Central Park. “That public gesture, making something that only lasts for a few weeks, and putting all that energy into something that dissolves, that turns me on.”

Keene says he receives two or three orders a day from Ebay, where he sells his own work, and around the same number from his website, where people can order five paintings “that kind of range from large to medium” for $30, plus shipping. “People don’t get a choice,” he says. “They get what I wrap up. I’ve been doing this so long they know what they’re gonna look like. I just pick what looks good and I try not to rip the people off.”

People frequently resell his work, too, which to my surprise he doesn’t seem to mind. “At this point they’re kind of like an American collectible. I never fell into a category, because I was never a graffiti artist, and I was never a gallery artist, so it was more like I make collectibles [laughs] which is cool. It’s very American.” I ventured to suggest he was like a Brooklyn Grandma Moses, half-expecting him to protest, but all he said was, “I’d love to be Grandma Moses.”

During a recent residency of sorts in which he painted outside the Brooklyn Public Library, Keene said, he was recognized frequently. “People would come up to me like, ‘Oh man, I bought your pictures like fifteen years ago when I went to the University of Kansas, you came and did something one time,’ like, wow. For not being successful or famous, a lot of people seem to know me. [laughs] It’s pretty weird. My work’s all over the country in people’s kitchens and bathrooms.”

But the strangest place he’s seen his work is at Sotheby’s. “JFK Jr. had a bunch of my pictures, and about ten years ago they were being sold at Sotheby’s with various Kennedy estate stuff. In the catalog it said something like, ‘Anonymous Artist’—nobody knew where they were from. There were five pictures and I think they went for like $12,000, and I thought, ‘Oh boy, I don’t want to tell the people they’re only worth, like, eight bucks.’”

He enjoys going to museums, he says, and doesn’t get to galleries much. “Galleries take too much work. And you see the same mopey people in ’em.” Of the New Museum, which he doesn’t care for: “Everybody’s depressed, everybody’s about to graduate from art school. It’s a pretty building, and the art they show in it is perfectly valid, but there’s something about the combination. It’s all kind of insane—I know I sound like an old curmudgeon now—but the reason why I do the work that I do is that it’s a total reaction to the way the world is supposed to work.”

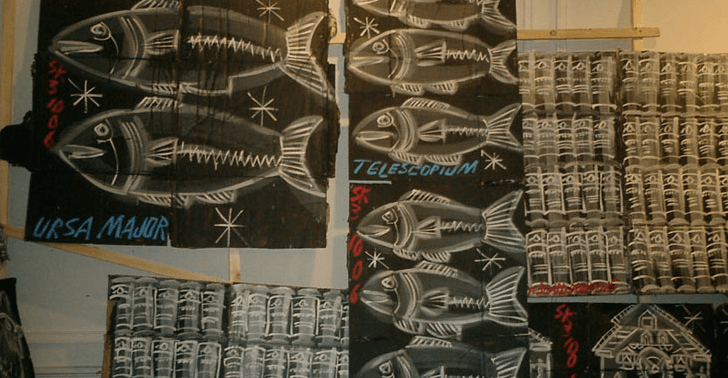

Exhibition at PACE University, 2006

In addition to painting, Keene is experimenting with drawing in AutoCAD and Rhinoceros, cutting and “tattooing” plywood with a CNC table router, which is controlled by a computer program. The precision of this process and its distance from the artist’s hand seems like the polar imaginable opposite to his painting, which is choppy, imprecise, and immediate. “It’s a total reaction from my hand-painting,” he says. “With this, I’m making art but not touching it, it’s all like this [makes a two-fingered scrolling motion]. The physical performance is so beautiful. This [scrolling] is the physical performance and this is just the machine, with nothing in-between really.”

He’s not as eager to sell his 3-D work in the same way he sells his paintings, but is amassing them slowly. He’s shared some of his work Twitter, which he admits he doesn’t really understand, but his kids are helping him.

“If I don’t feel particularly successful with something, I think, ‘How many people are doing this?’ There’s really not that many people in the entire world that have devoted so much time and so many years to doing what I do. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but at least people have noticed. It’s like I’m connected to people without knowing.”

Check out Steve Keene’s website for paintings, pictures, and more information. He’s also on Twitter @keene_steve.

Follow John Sherman on Twitter @_john_sherman.

You might also like