Return to Sender: The Strange Demise of The World’s Number One Elvis Fan

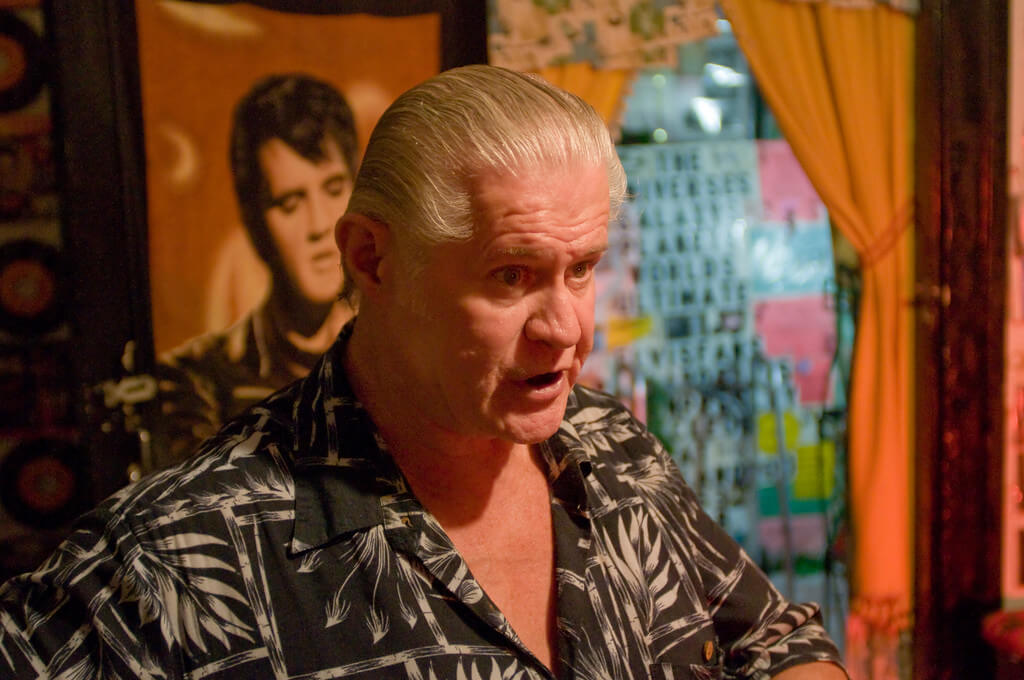

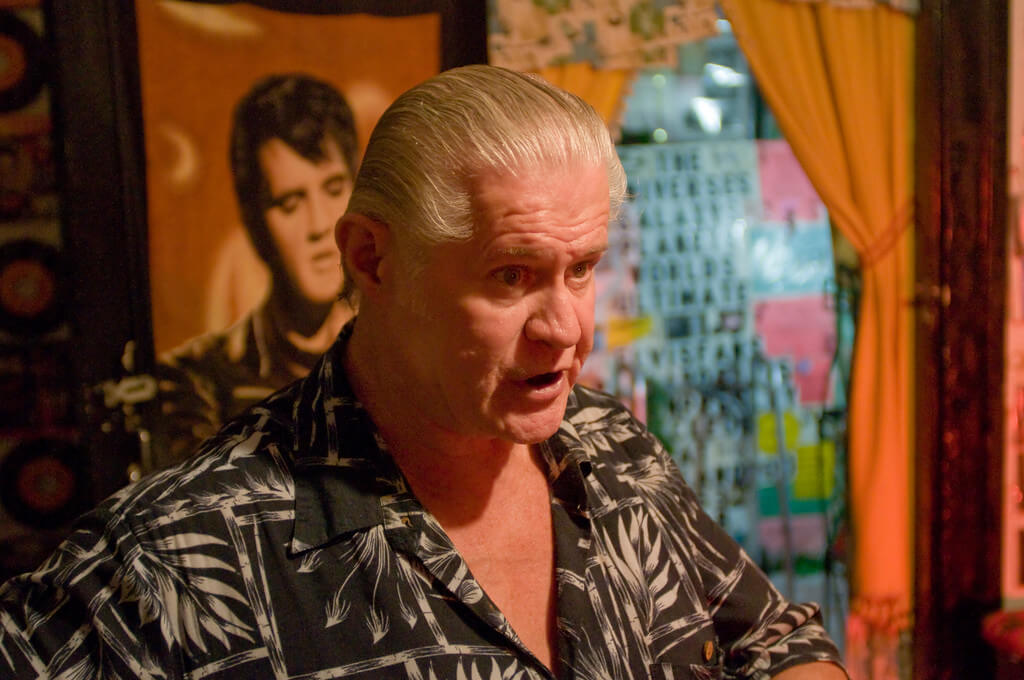

Paul McLeod, the owner and operator of Graceland Too. Photo courtesy Nick Russell

Holly Springs, Mississippi is a town famous for two things: Ulysses Grant’s brief stay during the Civil War and Paul McLeod, the world’s number one Elvis fan. There are few, even in the hotly contested world of tribute to Presley, who could come close to McLeod’s devotion. A retired autoworker who neighbors gently termed “an eccentric,” McLeod dedicated his life to acquiring every piece of Elvis memorabilia he could get his hands on. He had claimed to name his son Elvis Aaron Presley McLeod. He often recounted the story of choosing Elvis over his ex-wife. “She said, ‘It’s me or him,’” McLeod would recount brightly. “And I gave her some money and said, ‘So long, darlin’.’” He transformed his home, a two-story number tucked into a cul-de-sac, into a roadside museum to the King. At first the house was white, but McLeod periodically painted the entire exterior vivid pink or blue for Elvis-related occasions. He affixed a pair of stone lions to the wall outside, mimicking the sweeping walk up to Presley’s home. Faded ice-blue tinsel trees dotted the property, erected in honor of Blue Christmas and left to weather the Mississippi summer heat. He called the place Graceland Too. Word of the attraction spread by word of mouth and sporadic press reports on McLeod’s personal Elvis Smithsonian. Folks on their way from Memphis to Jackson or Birmingham to swerve off the highway and into the cotton-pocked fields of the Delta to see it. It became Holly Springs’ number one tourist attraction.

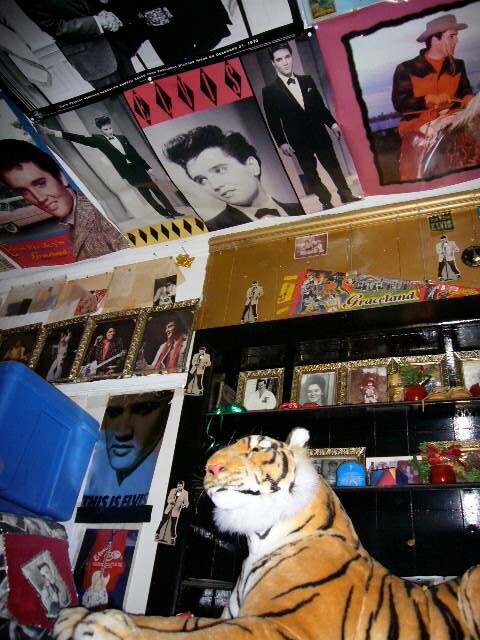

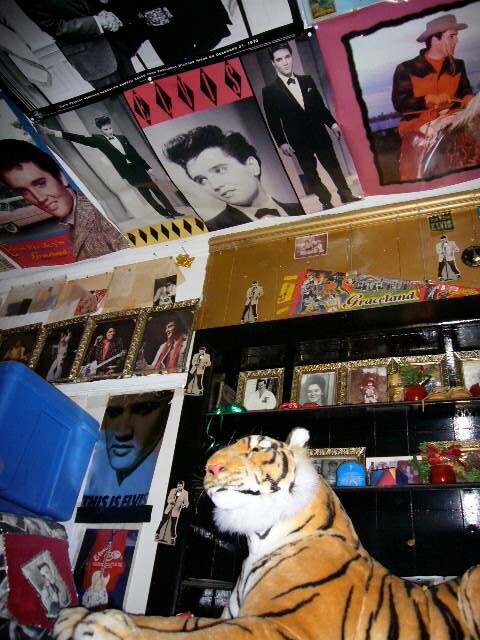

Graceland Too was open 24/7, every day of the year. You would simply knock on the door loud enough for McLeod to hear, hoping that your visit coincided with the odd hours he chose to be awake. McLeod, his silver hair swept back into a deflated pompadour and his false teeth not quite adhered to the top of his mouth, would stumble to the door and usher you into a musty foyer wallpapered with Elvis pictures and clippings. On the staircase landing, McLeod had proudly fastened a sign in stick-on letters. “This is Elvis Land,” it announced. “The Universe’s Galaxy’s Planet’s World’s Ultimate #1 Elvis Fans Paul and Elvis Aaron Presley McLeod,” another boasted.

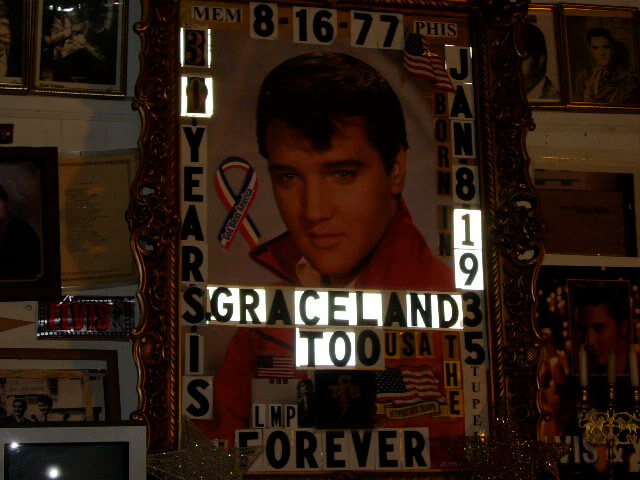

The cost of a guided tour, one that varied wildly in length depending on how loquacious McLeod was feeling, was five dollars. Three visits earned you a lifetime membership, which included free entrance, a little pink cardboard card with “Graceland Too Lifetime Member” stamped on it, and a picture of you wearing one of Elvis’ leather jackets which McLeod would then carefully tack to sheets of poster board he kept scattered about. In the living room, McLeod encouraged guests to take pictures under a framed picture of Elvis on the mantelpiece, more vinyl letters haphazardly marking the date of Elvis’ birth and death on it. It was the sanctum of Graceland Too, the altar of the giant shrine that McLeod had constructed.

Entering McLeod’s house required a certain suspension of disbelief and an advanced tolerance for junk. Much of McLeod’s collection was no doubt valuable—certainly the 45s displayed on his walls would make many record collectors’ eyes glitter—but a far greater proportion of it was the sort of memorabilia that regularly ends up in Memphis-area thrift stores. The house always seemed on the verge of bursting from the sheer amount of stuff in there, the result of decades long spates of singularly focused hoarding. McLeod had trunks full of videocassettes, culled from a bank of televisions, aimed at recording and logging anytime Elvis was mentioned or a song of his played on any television channel. Tucked into corners of his gloomy living room were dozens of toothbrushes, bobbleheads, beach towels, novelty plates, figurines, and other assorted tchotkes having to do with Presley. On one of my visits, McLeod proudly displayed a bag of dessicated grass clippings taken from Presley’s grave.

Part of the game of Graceland Too was figuring out what percentage of what McLeod told you were lies. People came to visit as much for McLeod’s personality as the reliquary of Elvis stuff he had. McLeod peppered his visitors with yarns about Elvis’ coterie, Elvis’ favorite foods, Elvis’ favorite Elvis impressions (Andy Kaufman, by a long shot). The first time I visited was on a trip with my high school, in which my teacher cautioned McLeod to give the “clean version” of the tour, thanks to the amazingly creative use of profanity he usually put on display. I returned to Graceland Too every couple of years after that, whenever a visitor from New York came to visit me in Mississippi. One time, McLeod whisked me and my bewildered college boyfriend around town in a battered gold limousine that he supposedly purchased from one of Elvis’ inner circle, chattering about Jerry Lee Lewis, who lives nearby in an estate known locally as “Disgraceland.” During most visits, he claimed to have a coffin emblazoned with “Return to Sender,” ready to go on the event of his death. He hoped to be buried in his Elvis suit.

The inside of Graceland Too. Photo by Nick Russell

Graceland Too was always a far better tourist destination than actual Graceland. The difference between them was like a homemade Halloween costume compared to a store-bought, mass-manufactured one. Graceland, as a monument to Presley, offers little clue about why the man inspired such a fever among his followers. The rooms are roped off, the audio tour expertly polished. Little of Elvis’s messier side—the booze, the dizzying ascent to stardom, and the alleged affairs—is detectable from the garish shag carpets and seashell lamps on display. It is, as Greil Marcus wrote, “a 1957-1977 version of King Tut’s tomb,” where Elvis’ absence is the most palpable thing about the place. What Graceland mummified about Elvis, Graceland Too brought back. McLeod’s lovingly crafted monument, nothing less than a masterpiece of outsider art, conjured up the spirit of Elvis better than the hollow rooms of any museum ever could. It is easier to see gods through the people that worship them.

Behind McLeod’s bottomless knowledge of Elvis trivia lurked darker thoughts, outlandish conspiracy theories about the government and rats being planted in cans of Pepsi Cola. (McLeod was a devoted fan of Coca-Cola, downing, he claimed, up to 24 cans of the stuff a day. “It makes me horny!” he would shout lasciviously at any young women on the tour.) Some of his favorite stories was about waking up to trash bags full of cash on his stoop, and turning down grand offers from visiting billionaires hoping to buy his collection. He claimed that various dignitaries and world leader had come to see him under the cover of night, including President George W. Bush. He was terrified of arson, of burglars, of any force that might wrest his life’s work from him. His fears seemed exacerbated by certain groups of Ole Miss students who would drive over from Oxford to pound on his door at all hours of the night after imbibing sufficient quantities of jungle juice and Bud Light to eliminate any engrained politeness. A few of them, much to McLeod’s distress, had pocketed souvenirs of their visit. In the backyard, McLeod kept a prop electric chair, and dared guests to sit in it. On one visit, I spotted a grenade, presumably fake, in the midst of some cartons of Elvis-themed ice cream, perhaps placed there as a warning to would-be intruders On my last visit, he pointed out a padlocked cabinet in the back with “DEEP LOCK GUNS SHELLS” emblazoned on it.

Last week, McLeod must have cracked that cabinet open. On July 15 at around 10:45 pm, McLeod heard a banging on his door. “Of course, people would bang on his door all the time,” McLeod’s lawyer, Phillip Knecht, told me. “But this was different, more violent.” A local handyman, Dwight David Taylor, broke the glass on his front door, forced his way inside the house and demanded money. McLeod shot Taylor in the chest with a single .45 caliber bullet, killing him.

Reports about why Taylor was there varied. Taylor’s mother, Gloria, told Memphis news station WREG that he was going to collect money for helping paint the house, money that McLeod had refused to pay him. Taylor was known for doing odd jobs around the community to get by. His reputation varied, depending on who you asked. Kelvin Buck, the mayor of Holly Springs who is also the acting police chief, told the press that he was treating the incident as a home invasion. “The resident of that house felt that his life was in danger and took action,” Buck said.

On Thursday morning, less than 48 hours after the shooting, McLeod was found dead on his porch. His body was slumped over in a rocking chair emblazoned with Elvis’ “TCB” logo, shorthand for “Taking Care of Business in a Flash.” He was 70 years old.

The county coroner attributed the death to natural causes. The outpouring for McLeod was immediate. Fans began leaving empty Coca-Cola cans and bottles with notes of thanks and remembrance tucked in them on his porch. For the first time, a “closed” sign hung permanently on the door. “In the past week, I’ve gotten hundreds and hundreds of emails from people all over the world. I’ve accidentally become Paul’s PR agent,” Knecht said. “Before Paul hired me on Wednesday, I had never gone on the tour. But he forced me to, even as I was asking him questions about an upcoming criminal trial. I was the last one to go on it.”

The criminal charges over Taylor’s death go to a grand jury in October. McLeod’s autopsy results will take months. The legends around him have already begun to unravel. “That famous story about how he gave his ex-wife a million dollars because she made him decide between him and Elvis is false, unfortunately,” Knecht told me. He had gotten in touch with McLeod’s ex-wife, who hadn’t spoken with him in many years. “We’re not even 100 percent sure how he spelled his last name. His family spells it MacLeod, even though all of us in town knew him as McLeod.”

Nor could Knecht locate the famous “Return to Sender” coffin, or even any written will. His body will likely be cremated. His son, Elvis Aaron Presley McLeod, who once gave tours alongside his father, is rumored to be estranged from the family business and living in New York somewhere. Knecht has yet to track him down. There are plans for a public memorial on Elvis Week, the annual carnival of King-worshippers marking the musician’s death on August 16. Knecht and the Holly Springs tourism board will open the house one last time to McLeod’s fans on August 12 as a benefit for his funeral expenses. There’s even a call out to Elvis Presley Enterprises, the company that runs Graceland and routinely disavowed McLeod, for help memorializing him.

It’s unclear what will happen to the estate of the greatest Elvis fan who ever lived. There are hopes that much of the house’s inventory can be turned into a museum of some sort, a plan that the mayor and aldermen of Holly Springs are behind, Knecht says. Sifting through the vast amount of Elvis paraphernalia will no doubt take months, and the process of transforming McLeod’s collection into a more streamlined exhibit would give even the most seasoned curator nightmares.

But this much we know: Those of us who had the chance to see Graceland Too can count ourselves lucky. Paul McLeod has left the building. The King is dead. Long live the King.

Follow Margaret Eby on Twitter @margareteby

You might also like